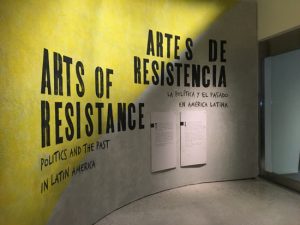

The “Arts of Resistance” exhibit at the Museum of Anthropology located in University of British Columbia campus and curated by Laura Osorio Sunnucks, is composed of several cultural artifacts that explore Latin American folklore as well as its implications in modern society. The purpose of this exhibit is to provide visitors with a better understanding of the political implications that these cultural and folkloric artifacts take in face of larger societal issues. Since the exhibit is based on Latin culture, it provides information regarding the history behind each object both in English and Spanish. Similarly, the exhibit although contained in one room can be divided into different sections following a particular theme. These sections include the Maya dresses and the role of women, the maize installation and the impact of modern agricultural techniques in traditional crops, and representations of the devil as a response to colonialism.

Photo credit: Tara Lee

Photo credit: Tara Lee

The main question that arises from my visit to the exhibit is regarding the similarities shared by Latin American countries in terms of culture and current social issues. The countries whose art were exposed included Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, El Salvador, Ecuador, and Chile, yet coming from a Latin American country myself, I felt that the injustices being fought and the art being expressed were very close to Brazil’s reality and culture. Not only do all the pieces at the exhibit share in common their colorfulness, but also they share an intensity and feeling of perseverance that we Latinos know very well.

One of the features that I found particularly noteworthy was the representation of womanhood and female empowerment. The first objects to draw the visitors attention when entering the exhibit are the Maya dresses, called huipiles, which have a square format symbolizing the structure of a house or from a different perspective the four corners of the world. The space designed for the head lays right on the center of the huipil, associated with the central space occupied by the heart in the human body. These meticulously weaved dresses are worn by women and are connected to fertility and the womb, according to the Maya. Similarly, a large canvas under “The Defence of Maize” installation also has a woman as its central figure. The stenciled mural includes pre-hispanic symbols of maize, the pre-hispanic maize goddess Centeotl and an Indigenous Oaxaca Mixe woman who is pointing a gun at the scientists responsible for the introduction and development of transgenic maize. Although the artist Lapiztola is Mexican, the maize plays a pivotal role in most Mesoamerican cultures and cuisines. I found it interesting how the different types of media were used for the visitor to understand the importance of this crop in Mexican culture and as a result in Mexican society. The colors used on the panels, neon green and yellow, serve as a criticism reminding us of radioactivity and suggesting the genetic modifications done by the scientists to the crop. Right in front of the panel through speakers, visitors can listen to a person asking “como se llama maize en la lengua…”, (how do you call corn in the indigenous language…), bringing to the exhibit the aspect of oral tradition.

Based on what we discussed in our ASTU class about Sarah Polley’s documemoir Stories We Tell, we can compare the use of different media in both settings. In Polley’s film, which is based on interviews done with family members and friends in order to reconstruct her mother’s story and explore the notion of memory, she uses real recordings of her mother mixed with fake recordings in which she directed the actors. In both forms of art, the exhibit and the film, the language and visuals are intertwined providing the audience with a greater perspective upon the subjects being portrayed, the importance of maize in Mexican tradition and the story of Sarah’s mother.

Moving forward through the installation, visitors see the large mural and right by the end two traditional grinding stones used across Mexico’s history and cuisine. Additionally, the fact that the installation does not follow a chronological order by ending with the oldest object, the grinding stones, illustrates the aspect of resistance and support the arguments of Indigenous ownership expressed in the panels, speakers and mural. Another element of contrast is how the mural developed by a street artist is placed close to the grinding stones, suggesting that modernity and tradition cannot be separated. Despite the fact that Indigenous communities in Mexico are experiencing challenges regarding the culture of maize, the final statement of this installation is that traditional practices will persist.

Photo credit: @MOA_UBC

Photo credit: @MOA_UBC

Besides its political stand, the maize installation helped me better understand the concept of power discussed in Political Science. Power, as we studied, is connected to the use of coercion, while authority is associated with legitimacy. The fact that the Indigenous Oaxaca Mixe woman uses force, literally by pointing a rifle, demonstrates that she has power over the scientists. On the other, it is generally known that in Latin America Indigenous people are not given power or are able to exert power. The government exerts power by using force and physically changing the traditional crop’s genetic composition in exchange for profit. The only thing left for the woman to do is resist which is what the mural is portraying, a distant reality in when the true owners of the land will have power and turn it into authority gaining governmental legitimacy over their traditions.

After reflecting upon the exhibit I was left wondering what was the process the curator, Laura Ossorio, went through in order to acquire these cultural artifacts. Part of me feels proud and strengthened by these people’s resistance, yet another part of me wishes that my country was also present. I wish other countries, who not typically associated with being part of Latin America and speak languages other than Spanish could take part in the exhibit, for instance, countries including Suriname and the French Guiana.