by Sofia Cuyegkeng and Shirin Eshgafh

Refugee children are dying while in the custody of the US Customs and Border Protection Agency — is the American government guilty of humanitarian crimes? Who is to blame? Why is this happening? It is clear from expansive academic research that the way the refugee ‘crisis’ is viewed by many states and in many societies is a problem. According to UNHCR (The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), there are 25.4 million refugees in the world as of the end of 2017. They are all someone’s father, mother, child, friend, etc. There is nothing that makes them any less human than any other person in the world. So why are they being dehumanized? How? And, what does this imply for American immigration policy and international law?

How are refugees dehumanized?

Refugees — Lives worth saving?

Discourses and narratives about certain groups shape the spaces they occupy in society. A prominent Social Justice scholar, Judith Butler, observes that: “On the level of discourse, certain lives are not considered lives at all, they cannot be humanized; they fit no dominant frame for the human.” In essence, Butler outlines how the nature of ‘otherness’ is born within discourses that seem to normalize its presence. This ‘otherness’ then leads to what Butler terms as “grievability.” When criminalized lives are thought as “less than”, Butler argues, their lives become “ungrievable” in that “[..] lives are supported and maintained differentially, [..]. Certain lives will be highly protected, and the [denial of] their claims to sanctity will be sufficient to mobilize the forces of war [whereas] other lives will not find such fast and furious support.” Basically, in marginalized communities, such as those occupied by refugees, negative discourses can affect their access to opportunities or even the right to live.

The Role of the Media: Refugees as the ‘Enemies of the State’

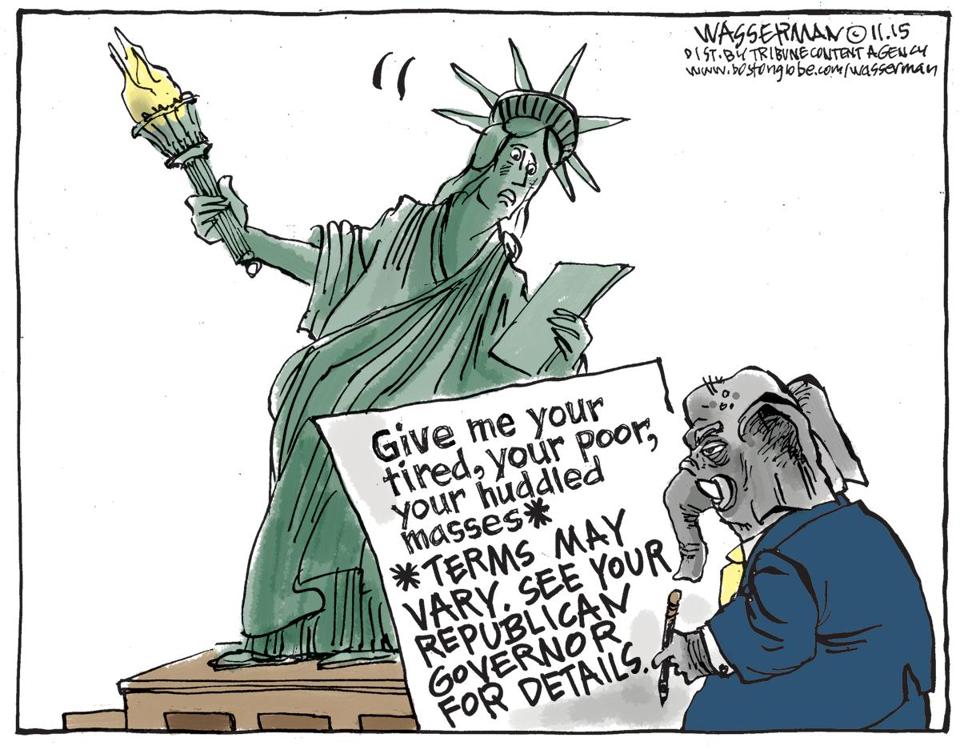

When discussing what shapes discourse about refugees, the role of the media is inevitable. Professor Victoria Esses and her colleagues at the Western University Department of Psychology conducted a study in order to measure the media’s influences on generating discourses about refugees. They focused on how these negative discourses affect the public’s perception of refugees. To do this, they exposed people to anti-refugee news articles/political cartoons, and analyzed how these sources influenced their perception of refugees. From this study, they came to the conclusion that the media “plays a large role in framing public policy and discourse about immigrants and refugees.” This is mainly because migration is heightened in this era of global conflict, thus the implications of accepting refugees are often discussed extensively in host (often Western) countries, which as these scholars add, creates much uncertainty and fear about these groups.

The Media on Refugees: Are they from Mars?

Media outlets take advantage of these hostile climates to generate negative narratives about refugees, in order to identify a ‘common enemy’. The framing of refugee communities through a biased lens serves the means of labeling these groups as the terrorist, diseased, undeserving, and in Esses’s words, the “enemies of the state.” To take one example, the term ‘alien’ is used widely by media outlets, such as Fox News, as a way to refer to refugees/immigrants without legal status. Referring to these groups as ‘aliens’ dehumanizes their existence in society, which may serve a greater political agenda of generating a sense of community, and collective identity among people, who may feel like their own citizenship/national identity is threatened by the arrival of refugees. The state can then use the media’s identification of the ‘common enemy’ as a means to generate concrete solutions to an identified problem and, in the process, create confidence in government.

Just a Number, Just Another Face

Furthermore, refugees are dehumanized not only in the words of the media, but also in the way they are visually depicted and reported by the international agencies meant to help them. In this way, not only does the dehumanization of refugees play an impactful role in state governance, it also deeply affects the personal lives of refugees in the way they are treated, largely overlooked, and left to suffer with the loss of personal identity.

Quy, one of the main characters in Dionne Brand’s “What We All Long For” explicitly describes in a first person narrative what it is like to be dehumanized as a refugee. Separated from his family in the chaos of fleeing Vietnam at the end of the Civil War, Quy is stranded in a refugee camp called Pulau Bidong as a young boy. One of his earliest memories is of a photographer who takes a picture of the many abandoned refugee children who populate the camp. He describes how “I’m the one who is smiling brilliantly less and less [in the photograph] and then giving up…more and more. I don’t suppose it showed up in the pictures” because “[w]hen you look at photographs of people at Pulau Bidong, you see a blankness…We look as one face — no particular personal aspect, no individual ambition. All one…Was it us or was it the photographer who couldn’t make distinctions among people he didn’t know? Unable to make us human.”

In addition to this dehumanizing visual depiction of refugees, Quy then goes on to describe his frustration with the officers from UNCHR who visit Pulua Bidong. He criticizes them for the fact that “[a]ll they did was count us and write reports,” underlining how refugees are reduced to a number with no substantive action being taken to help them. This first hand perspective of a refugee — although fictional — is based on reality and drives home how refugees are often considered a faceless, mass problem, something to be counted and then done nothing about. So now the real question is, why is nothing being done about their plight? Why are they so easily and pointedly dehumanized by the media and the state?

Why are refugees dehumanized?

Thinking Like a State: Stateless? Not MY problem

Under international humanitarian law, all people are supposed to have rights on the single basis that they are human. However, Professor Lindsey Kingston from the Institute for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies of Webster University, aptly points out that “in reality there are clear linkages between citizenship status and one’s ability to access fundamental rights.”

Kingston associates the differential treatment of lives to the notion of citizenship. She claims that that legal citizenship determines who counts and who does not. Thus, because stateless people are “not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law” according to the UNHCR, they are thought of, by other nations, as second-class citizens. And in turn, this lower status causes the numerous violations committed against them to be overlooked.

Why? What do states have to gain from this neglect of refugee rights? Or rather, why are they unable to do so? Simply put, resources are finite. The main purpose of any state is to protect and serve the interests of its people. More specifically, it plays a significant role in determining the allocation of resources. There is only so much land, funds, and other resources to go around. An influx of refugees can theoretically overburden the capacity of a state to provide for its people.

The Red Refugee Scare

There is the even more poignant concern of the possible threat refugees pose to national security, especially in the context of rising Islamophobia. The protection of borders has become especially significant for Western countries post-9/11. Carrie Dawson, an English professor at Dalhousie University who writes about migration, citizenship, and literature (among other things) aptly summarizes this sentiment by quoting the words of Peter Nyers: “the state tends to smile only on the most demonstrably abject of asylum seekers, those able to prove that they are utterly powerless, hopeless, and innocent. Where they are deemed to have any agency, that agency is typically understood as “unsavoury” (they are identity frauds or queue jumpers) or “dangerous” (they are criminals or potential terrorists).” Due to the crippling fear that surrounds the security threat refugees may pose, it is in the states’ interest to limit the amount of refugees entering their territory, especially if this sentiment is popular amongst their citizenry and (in the case of a democratic government) they wish to remain in power (through re-election).

America: “Land of the Free” Human Rights Violators

The state theoretically cannot take in all refugees due to both limited resources and the security risk refugees present. On these grounds, it is in their interests to dehumanize refugees (or at the very least make them seem like a problem) in order to make citizens see them in a negative light and discourage popular support for helping refugees. If you dehumanize refugees enough that society no longer considers them human, then the violation of their rights is theoretically no longer considered a human rights violation.

For example, in the United States, children as young as seven years old are being forcibly separated from their parents at the US-Mexico border. According to CNN, almost 40,000 migrant children have been taken into custody this month at the US-Mexico Border. In fact, the US Customs and Border Protection commissioner says that the US immigration system is at a “breaking point.” Many of child refugees are below the age of reason, not yet finished with school, but are expected to represent themselves in an immigration court conducted in a language they do not understand and with no legal counsel. Several separated refugee children have actually died while in the custody of the US government services like seven year old Jakelin Caal Maquin from Guatemala who died in December 2018. This is because the refugees are being housed in inadequate shelter with inadequate basic necessities like water and medicine. Photos and videos show them locked up in cages like animals; such as the situation in Texas reported by NBC News on March 28, 2019 where refugees were kept “confined to a chain-link enclosure” under a bridge of all places.

“All [people] are equal but some [people] are more equal than others.” — Animal Farm by George Orwell

So, it is that clear human rights are being violated, but who is supposed to hold the US government accountable? Theoretically, it is the duty of the United Nations. The problem is that the UN’s refugee policy is flawed. According to Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, refugees have the rights to seek asylum in other countries when fleeing persecution. This is again underlined in 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which expands on other rights refugees are entitled to such as housing, legal counsel, etc. However, the wording of the 1951 Convention is not truly legally binding. Using language like “recommend”, the Convention is not ‘ordering’ a state to adhere to a strict set of rules, rather it reads more like suggestions for the treatment of refugees. For example, the Convention “Recommends Governments to take the necessary measures for the….protection of refugees who are minors, in particular unaccompanied children and girls…” Furthermore, the United Nations cannot force states to make refugees citizens — to do so would be intervention in the internal affairs of another state and a violation of that state’s sovereign autonomy. However, it is citizenship that truly legally ensures that people’s rights are protected. So as Kingston puts it, “[i]f rights are indeed universal and inalienable, then our reliance on legal nationality is not only inefficient – it directly violates the foundational norms that established human rights in the first place.”

Changing the Script

Ultimately, yes the American government is at the very least partly responsible for their unjust treatment of refugees. However, the international system that is supposed to hold them accountable is also flawed, and the media has played its own role in influencing society to see refugees as a subhuman problem. All these factors reinforce each other in a cyclical pattern that ultimately makes the dehumanization of refugees a societal problem at its core. In order to undo the dehumanization of refugees, the change needs to start in people’s minds.