When the telegraph was introduced the intention was to quicken communications across long distances. This gave rise to a series of consequences, both intended and unintended. It also gave rise to changing forms of labor and of dissent, to different ways of understanding the “global”, as well as involving changing norms about gender and intimacy.

By way of introduction to some of these themes, as well as a way for you to see how these machines actually worked, and how important labor was, watch this 1942 video:

Take some notes on what you see, and we’ll talk about it in class.

One of the more apparent features of this video is how communications work became gendered. Here is a description of a telegraph office, by the famous novelist Anthony Trollope, which he wrote in 1877: The Young Women at the London Telegraph Office.

The telegraph was implemented on a global scale, and one of the interesting ways to think about media history is to consider how these technologies translate when they are transplanted to very different contexts. As a way to hold empires together, telegraphy proved both essential and subject to contention. Here is an article describing some of these dynamics:

“Of Codes and Coda: Meaning in Telegraph Messages, 1850-1920, by Deep Kanta Lahiri Choudhury

Space and Time

Finally, telegraphy accompanied changing notions of space and time. It’s almost a cliché these days to say that the telegraph shrank distances, bringing places closer together through the ability to communicate faster between them. This may be true, but it’s important to emphasize how bumpy and uneven that process was.

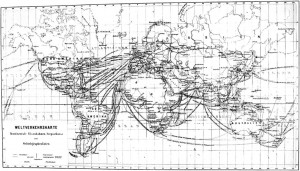

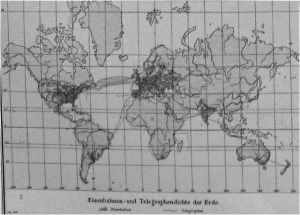

Maps became a very useful way to envision the telegraph connections around the globe. In fact, some historians argue that these maps got people thinking in global rather than national terms, and reminded them both of what was connected and what was not.

‘Map of world Verkehr’. Source: C. Merckel et al., Der Weltverkehr und seine Mittel, Leipzig: Otto Spamer, 1913.

Figure 1 Figure 1 ‘Concentration of railways and telegraphy on the earth’. Source: A. Scobel, Andrees allgemeiner Handatlas, 4th edn, Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1899.

Both of these maps are from an article entitled “How to See the World Economy: Statistics, Maps and Schumpeter’s Camera in the First Age of Globalization”, by Quinn Slobodian, Journal of Global History, Vo. 10, no. 2, 2015.

In class we’ll think about how these maps changed the way people thought of the global and the local, and the possibilities for connecting them.

22 responses to “#4 Telegraphy, Work, Space, Time”