Which is the mode I chose for this project . . . and which I’m trying hard to make a life mode, but so far, with rather less success . . .

The first thing I did was google the term, mode bending, which I totally love as an expression. I may begin saying, “wow, that was mode bending,” or perhaps, “that was a mode bending moment” (I love alliterations) . . .

Turns out, there are real mode benders. I took a screen capture:

The third one from the left, called an instrument bender, is one I recognize. I used it when, in a moment of madness, I spent a year training as a fitter-welder. This tool is a pipe-bender/fitter used wherever you see pipes (of any size) bending and curving their way through the world. A tube-bender likely used this tool or one like it to bend that pipe where it needed to go.

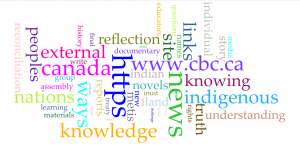

But, the real task. I was in a class last term where we played with a wide range of software to alter modalities from text to image to sound. It is a fascinating thing to do, and I did it for another class this term. This is the image I produced of a First Peoples lesson plan and discussion about multi-literacy, knowledge construction and self-reflection:

On the site, voyant.com, the image can actually move, etc., but I simply copy-pasted the graphic at a point where I liked the image, rather in the same way I often read and re-read the same passages or pages in order to enjoy the experience over and over again.

So the exercise is to use the original handbag assignment, and I’ll get to it, but I cannot resist playing (which is why I try not to go to these sites too often . . . they eat up hours of time) . . . but this is the result when I put my lesson plan on reflection, indigenous knowledge, ways of knowing and knowledge into Cirrus, a tool in voyant.com:

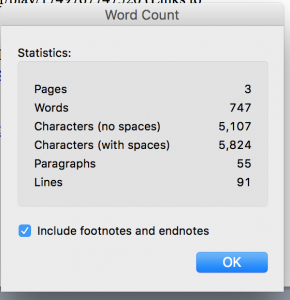

I worked many years ago with early software that did textual analyses using the above principles, but returning a list of frequencies (of adjectives, adverbs, nouns, etc.) to give an emotional level to the text. It looked more like the return you get in ms-word when you check word count, something like this:

It’s so easy now to see how the first visualization can support and alter ways of seeing and knowing. Using Cirrus, students can easily check and see what words and ideas are being put forward by the author and even re-write the material to change the slant to something they want to see. I’ve not used this tool yet in teaching, but I intend to use it with students to show them just how much their words matter and why it’s important they have the skills to critically analyse the words they see around them every day. Even with my own critical reading skills, I am always taken aback at how much the Cirrus visual helps me to ‘see’ what influence the words are working on me.

My purple handbag

I could not resist playing a bit, so I put the handbag assignment into some of the voyant tools, just for fun. Here are some links to the results:

https://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=b7b48a47fe3e80f3a5c81a7c2aaf70b6&view=Knots

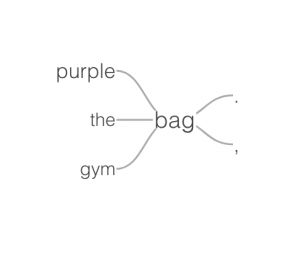

Some renditions were less appealing, as this one, using wordtree:

Still, the central discussion about the bag is clear in this depiction, as is the color, purple. How the word, gym, gained such prominence I do not know. It’s also curious how much the visual representation reflects the way the bag can be carried. If the words, purple, the, and gym, are viewed as shoulder straps, they hold the word, bag, in place. This particular bag has shoulder straps and the bag can be carried on your back . . . .

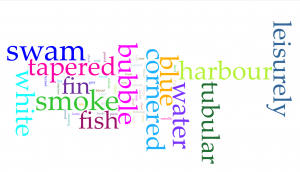

One of the appeals of these types of visual representations is that I think they can readily accommodate differentiated learners and allow them to discuss text equally with their peers. I took the poem, The Shark, and played with it to see how it might work to show meaning in different ways that might make understanding easier for students, all of whom struggle with ideas about metaphor, simile, etc., and that this poem illustrates well. I tried Cirrus, first, as it is one visualization I find useful:

I love it! It even looks tubular and fish-like! I think these kinds of visualizations might really engage students.

YIKES! Once again, playing has caused me to be late for another class . . .!

Later, same day . . . (I passed) . . .

What I particularly like about this site is that you can put your text (poetry, novel, news report) into the application and have it changed into an alternate mode. This can help alert students to how different ways of representing communication can influence how that information is received, interpreted, and understood; that is, MacLuhan’s point how the medium is the message.

As the New London Group (NLG) also argues, it is imperative, as multi-literacies become widespread, that students are taught how to use them and to ‘read’ them and that teachers are also capable of using them, reading them and teaching them (NLG, np). I agree with the NLG’s position that in order for 21st century citizens to fully and actively participate in their societies they must be literate in the literacies this century will foreground. Just as the last century foregrounded the print-bound text, this century may utilize other modes–visual, aural–to communicate.

NLG describe that learning to accommodate the new literacies requires them to be juxtaposed and integrated, to open students to the meta-languages they can now take advantage of and, most important, produce; it’s not just about the authority of the text as it lives in a print-bound page: “In an economy of productive diversity, in civic spaces that value pluralism, and in the flourishing of interrelated, multilayered, complementary yet increasingly divergent lifeworlds, workers, citizens, and community members are ideally creative and responsible makers of meaning” (NLG, np).

As Cope & Kalantzis (2009) note, the single standard of “grammar, the literary canon, standard national forms of the language” (p. 5) have given way to reading and writing in “multimodal texts integrated with other modes with language” (p. 5). As teachers and practitioners the need to become literate in technologies has perhaps never been greater. Thus, the letter of complaint signed by 103 students in the B.Ed. program regarding their incompetence with the simple platform Canvas should raise a massive red flag of warning.[1] Who will teach these new intersections and road crossings?

But, I digress. How to shift handbag to new mode? which mode? I finally settled on a free application, Natural Reader. Of course, I had some fun with it, too, slowing down and using various accents. I finally used it to produce this new material. I chose an accent from India because about 1 in 4 people come from India, and it emphasized to me how multi-lingualism (even if she is speaking in English) is an important component of multi-literacy.

So, I’ve told the story of Jack, really, and it occurred to me as I tried to justify why this story was a mode of the original that juxtapositions are part of multi-literacies and that a single authoritative story, in print, and bound in a book, doesn’t have to limit me any more. And the story of Jack tells also a story about the bag, my purple bag, that is different, yet part of, the photo I took of Jack and the bag, that suy day in Vancouver.

To play the story, click and the ms-word document will open up. Select “audio notes” from the upper left portion of the ms-word menu. Press play on the upper right. Adjust audio as needed. About 5 minutes listening.

It could use a new ending, or maybe there’s no ending. Add one, if you like.

[1] 103 B.Ed. teacher-students—many, Net-gens—recently submitted a petition to UBC complaining that they were not dealt a fair hand when, in an effort to save the 2020 Winter/Spring/Summer terms for as many students as possible, the university moved courses online for as many programs as possible (personal correspondence). It was a near-seamless transition and stupendous feat. UBC uses a single, simple platform to serve 65,000 students worldwide, but the Education students in Vancouver complained it was too hard for them, asking that administrators see their plight as analogous to the struggles of the children they practice-taught. UBC will graduate some 700 elementary and secondary school teachers in a few months with a number of them so confused by technology they compared their feelings of incompetence to the school children they are charged to teach.