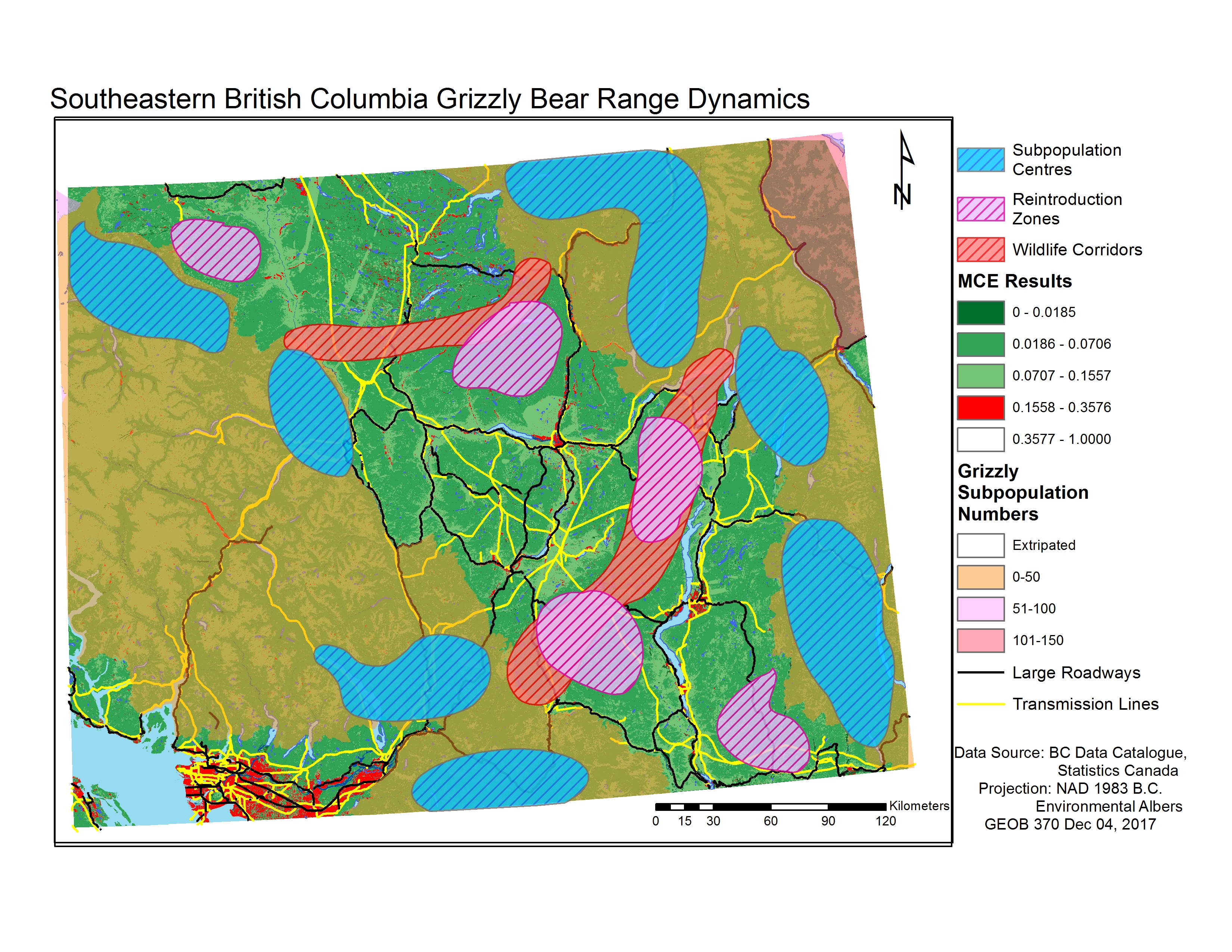

Fig 1. Final map of extant grizzly subpopulations in southern B.C., with potential subpopulation centres, wildlife corridors, and reintroduction zones highlighted.

Conclusions

In response to our initial questions regarding the vulnerable southern B.C. grizzly populations, we found that:

- Through our spatial analysis, we were able to identify potential high density regions within the extant subpopulations surrounding the extirpated Okanagan-Thompson, and most of these regions bordered this area.

- While there are still avenues for travel between the subpopulations separated by the extirpated Okanagan-Thompson region, it would be unlikely for bears to travel across it; fragmentation and human activity still occur within these high-score pathways.

- Successful reintroduction of grizzly bears into the Okanagan-Thompson is unlikely. The few optimal patches of unoccupied forest within the Okanagan-Thompson are still in close proximity to major urban centres, highways, and transmission lines.

From these results, we believe that these vulnerable subpopulations of southern B.C. will tend to remain isolated in the future, making them more vulnerable to future disturbance, stressors, and human activity. Concerted, sophisticated conservation efforts need to be undertaken within British Columbia in order to ensure these subpopulations’ long-term viability.

Uncertainty

There are a number of limitations and uncertainties inherent to our analysis, such as:

- Population estimates from 2012: this data is 5 years old now, meaning these subpopulations may have been extirpated or grown in size during this time. There is inherent instability when grizzly bear abundances are low like in the subpopulations dealt with in this analysis.

- Defined subpopulation: because grizzlies have large ranges the subpopulation units on the map may not be representative of the exact ranges of the bears within the subpopulation.

- Large range of values for subpopulation estimates: Most subpopulation estimates are in intervals of 50, and this is especially problematic for small populations like those we focussed on in this analysis; there is an enormous ecological difference between a region with 50 bears and a region with 1 bear.

- Land cover data only circa 2000: it is unclear how frequently or even whether or not it’s updated. Significant human development or fragmentation is likely to have occurred within the 17 years that separate this data and the present day, and we do not know whether or not this data has been updated to reflect those changes.

- Weighting inherently subjective: As with any MCE, the weightings are inherently subjective, and high habitat suitability in our analysis may not quite reflect ideal habitats for bears in reality.

Fig 2. An Alaskan grizzly. Photo credit: Princess Lodges.

Future Study

Evaluating habitat connectivity for important megafauna such as grizzly bears on larger scales than those evaluated in this project will be crucial in improving North American grizzly subpopulation viabilities. Partnerships with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y), the Coast to Cascades Grizzly Bear Initiative, and the Trans Border Grizzly Bear Project to conduct wildlife corridor and habitat suitability analyses on International scales will allow for greater understanding into the threats that these subpopulations face, and opportunities for conservation initiatives to reestablish connections and support vulnerable regions.