MCE Map

Fig 1. Final Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE) map.

The results of our Multi-Criteria Analysis identified regions with the greatest habitat suitability for grizzly bears (shown in dark green in Fig. 1) to regions with the least habitat suitability (shown in red). Areas of greatest habitat suitability are areas of relatively low slope, minimal human activity, and often within a forest/grassland ecosystem. The most unfavorable habitat areas surround the urban centres of the Greater Vancouver Area, Kelowna and Kamloops.

Our results did not yield really high MCE scores due to the large number of criteria we have included in our MCE weightings. Our fifth MCE category (values of 0.3577 to 1) is empty as there are no values within this range due to the low probability of multiple criteria overlapping in the same area (this would be equivalent to having a lake on a bridge in a city, close to a transmission line).

Sensitivity Map

Fig 2. Final Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE) sensitivity map.

The resulting map is noticeably different from our weighted MCE, due to equal weights being applied, the areas where the cells have several objects in them have the highest scores (Fig 2). To showcase this difference, we applied the same breaks as that of the weighted MCE. This sensitivity analysis shows that our weights have a significant impact of the results of the analysis. In this map there are unfavourable areas everywhere in the map, whereas the weighted MCE layer has unfavourable areas more closely grouped together, which is likely more reflective of reality (Fig 1; Fig 2).

Discussion

1. Where could grizzlies be found within these vulnerable extant subpopulations surrounding the Okanagan-Thompson?

Fig 3. Map of extant grizzly subpopulations in southern B.C., with highlighted potential subpopulation centres as outlined by our MCE.

In regards to where grizzly bears can be found within our study area, we have identified certain pockets within several subpopulations of where we believe bears would most likely be found (Fig 3). The selected pockets are areas with a high concentration of low MCE scores, which indicate regions of high habitat suitability for the bears. High habitat suitability involves areas with low slope, away from lakes and urban/agricultural lands, and are often in forest or grassland ecosystems. For the subpopulations located west of the extirpated Okanagan-Thompson region, the pockets we identified (pockets 1 to 4) are located on eastern side of the rugged terrain of the coastal mountain ranges. The pockets east of the extirpated Okanagan-Thompson region (pockets 5 to 7) appear to have larger areas of suitable habitat, which may be due to the less mountainous topography in this area (Fig 3).

However, it is worth noting that while we have identified pockets of high habitat suitability, the pockets are not contiguous both between and within each other, due to fragmentation from topography or some sort of human infrastructure (e.g. major roads) (Fig 3). Although some pockets are found in subpopulations that are considered viable (pockets 5 and 6), some of the pockets are found in subpopulations that are considered threatened (pockets 1,2,3,4 and 7) (Fig 3). This may likely affect the long-term success of grizzly bears living within these regions.

Lastly, although some of the identified pockets already fall within protected parks (e.g. E.C. Manning Provincial Park for pocket 4), and it has been reported that only one grizzly remains within this region (Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, 2017) (Fig 3). This indicates that while there are conservation efforts to support grizzly bears, they have not been successful in promoting an increase in population numbers.

2. Are there any wildlife corridors that could currently connect the subpopulations on either side of the extirpated Okanagan-Thompson subpopulation?

Fig 4. Map of extant grizzly subpopulations in southern B.C., with highlighted potential wildlife corridors as outlined by our MCE.

In regards to finding potential wildlife corridors across the Okanagan-Thompson landscape that is considered extirpated, we have found two connections across the region by looking for contiguous areas of low MCE scores (which involved largely avoiding unfavorable urban centers) (Fig 4). Even though there is potential for bears to cross using our specified routes, there are still obstacles along the way. It has been found that roads have a negative effect on grizzly bear habitat when they reach a density of 0.6km of road per sq km, with the effect increasing when road density rises over 1km of road per sq km (BC Ministry of Environment, 2012). In our study area, the Cariboo Highway divides corridor 1, whereas corridor 2 is intersected by Highway 5a, Highway 97, and the Trans-Canada Highway. Both corridors also cross the paths of several major BC Hydro transmission lines (Fig 4). These factors may hinder a grizzly bear’s likelihood of crossing along these corridors.

In addition, we should take into consideration the likelihood that grizzly bears will be able to travel the length of our specified corridors. Male grizzly bears have a home range of 1000-2000 km2, and usually travel or disperse long distances to find females for mating (Parks Canada, 2017). Female grizzly bear ranges tend to be smaller (200-500 km2) as their cubs limit the mobility of the mother (Parks Canada, 2017). Our corridor lengths are approximately 150km and 200km for corridor 1 and 2, respectively (Fig 4). Therefore, it is most likely for male grizzly bears to travel across our corridors during their mating season. Overall, however, due to the long distance that bears are required to travel along the corridors, it is still more probable for them to move within their own subpopulations, or between the subpopulations located on either side Okanagan-Thompson, than it is for them to move across the extirpated region.

Is a grizzly bear reintroduction into the Okanagan-Thompson possible, and where?

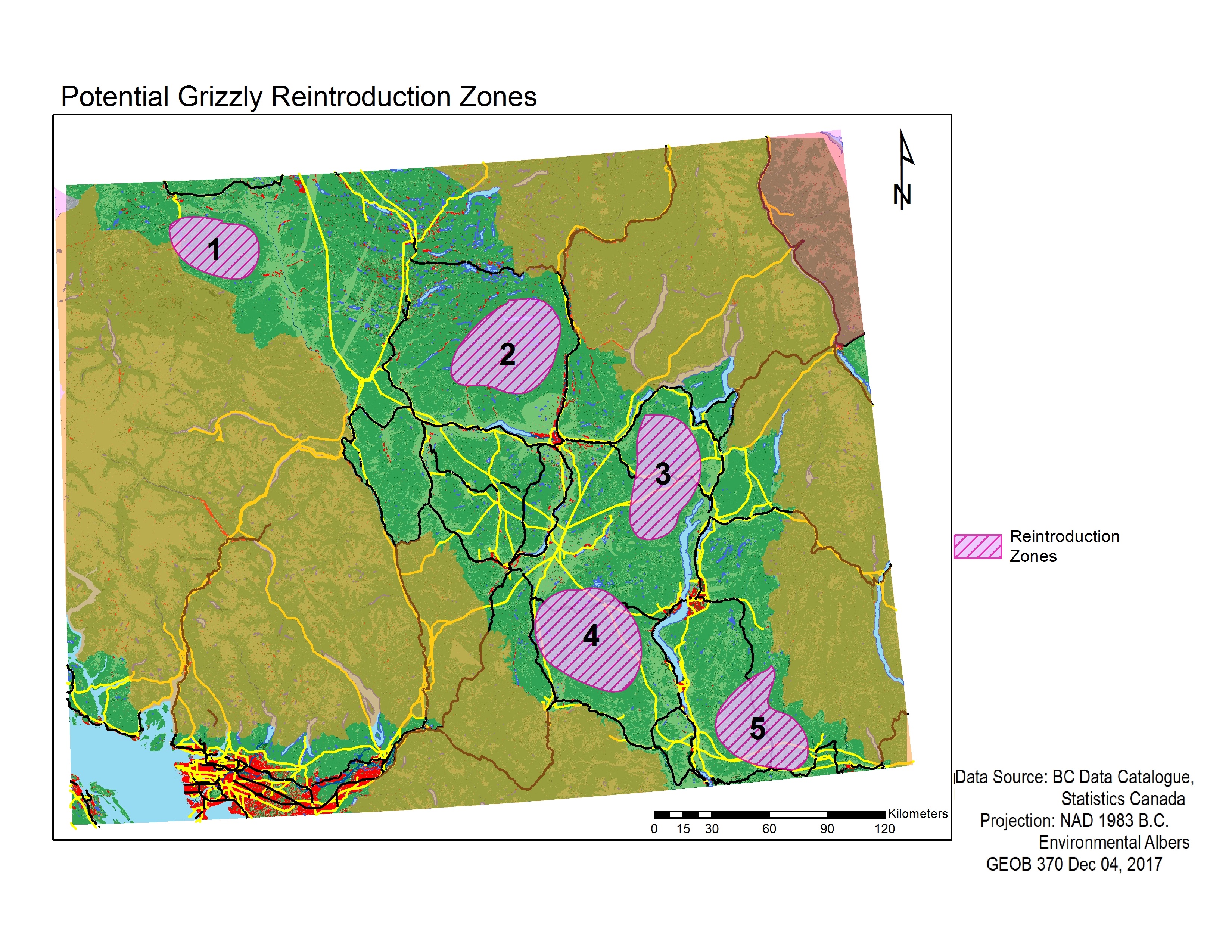

Fig 5. Map of extant grizzly subpopulations in southern B.C., with highlighted potential reintroduction zones as outlined by our MCE.

Our results also helped us identify areas within the extirpated Okanagan-Thompson region where reintroduction of grizzly bears may be most feasible, as we looked for large patches of low MCE scores indicating the greatest habitat suitability (Fig 5). Most of the possible reintroduction sites ended up bordering along urban centers (near Penticton for site 4, near Kelowna for site 3, and near Kamloops for site 2) (Fig 5). It has been found that the effects of human development is the greatest threat to grizzly bear habitat in British Columbia (BC Ministry of Environment, 2012). Should bears end up being reintroduced to the sites that we suggest, there could be potential for human-wildlife conflicts, which may result in bears being killed or relocated. Lastly, there are still areas with a high density of human infrastructure (e.g. roads) and unsuitable habitat within the extirpated region (Fig 5). This may cause some parts of the reintroduction sites to be alienated or fragmented as bears tend to avoid human activities. These factors will possible then hinder successful reintroduction to the region.