Reflecting on this week’s explorations, many aspects of the Connected Self and its disconnect in current educational practice have concerned me. In “Why School?” Will Richardson articulated the need for “different” education, not simply “better.” This stood out to me because I have witnessed a myriad of Ministry or administrative mandates regarding “integrating technology” in the classroom that all seemed like add-ons or poorly applied band-aids.

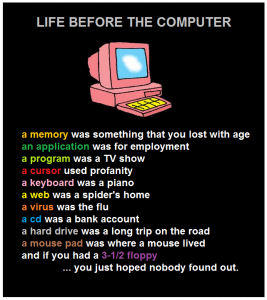

For example, in my school next year Grade 8 students, who once had an IT course, will now have a handful of sessions in the computer lab learning word processing and Power Point. Their “lessons” will be one period in the computer lab, separate and isolated from “the curricular” learning they were experiencing in Humanities 8 or Math and Science 8. The philosophy is that then students know how to use the tools and can utilize these skills in their future classes when the need arises. To me, this is a prominent example of the disconnection within the education system of the cognitive, cultural and technological dimensions of the connected self. For me, I believe that the cognitive dimension of the connected self is so disconnected within our schooling system that we are not unlearning and learning as our knowledge era reality requires. In TeachThought’s “How 21st Century Thinking is Different,” it is clear that “in an era of brazen technology,” in such new contexts as “digital environments that function as humanity-in-your-pocket—demand new approaches and new habits. Specifically, new habits of mind.” Currently, our education system is not adequately addressing these “new habits of mind,” and instead seems to launch into practices without the cognitive dimension as a guiding compass.

Furthermore, at the precipice of week one’s conclusion I find that the need for a concerted effort to integrate “The New Literacies” in the use of and through technology is very important to me. We opened class with a discussion of social media in education, and this is an area I would like to investigate as the course progresses. I think that many of the emerging literacies are involved in social media, and I would like to collaborate to explore how social media can be utilized to broaden perspectives, deepen understanding, develop a more unified cognitive, cultural and technological connected self within the classroom.