If you stopped five random people on a busy street corner and asked each of them to define the word ontology, you would probably expect to get a variety of reactions. Blank looks, huffed brush offs, hurried googling, drinks thrown in your direction, possibly someone ringing the police. All of those would probably be in there, but in a way, you might also come closer to that answer you were seeking than you realize.

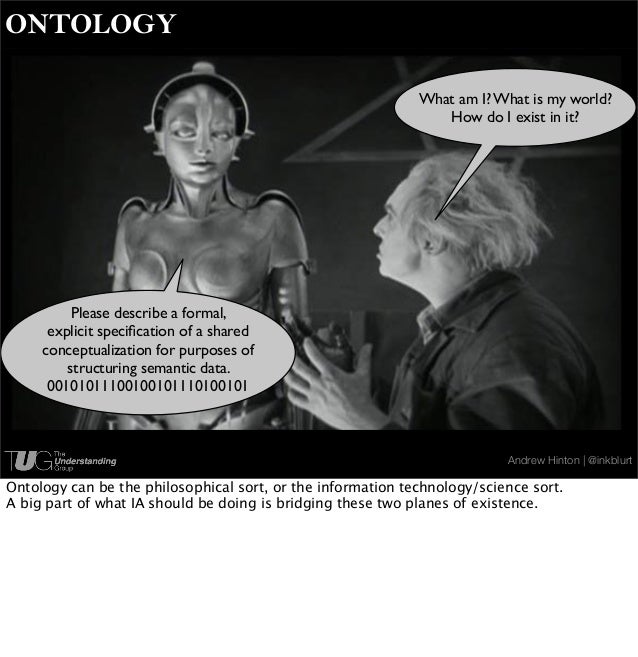

Taken From Google Images, Full Citation below.

Bagele Chilisa defines ontology as “the body of knowledge that deals with the essential characteristics of what it means to exist” (Chilisa, 20). More broadly, this could be interpreted as denoting what particular knowledge makes up a particular reality. Many of the readings covered in this course have dealt with the problems associated with different types of research methodologies, and how different perspectives can define different realities. In this essay, I will examine week 1 and week 2’s readings on the similarities and differences between various Indigenous, Feminist, and Transfeminist research methodologies, with a view towards examining how an multidisciplinary, intersectional research paradigm might help overcome some of the inherent biases common to some of these research methodologies and/or paradigms. In other words, using intersectionality as an intersection between different methodologies, in order to combat oppression of marginalized groups and voices. I will undertake this through a brief examination of the shifting nature of research paradigms and biases in different research areas, and how an intersectionality between these fields has shaped the changes which have occurred within said fields. Ultimately, I seek to highlight the shifting, diverse nature of any ontological research reality.

Chilisa’s discussion of western centric biases which persists in many modern research paradigms, and the problems associated with trying to decolonize these methodologies highlights a key issue which could perhaps be applied to most if not all research paradigms. I speak here of inherent biases. Hesse-Biber suggests that feminist research praxis’s use of reflexivity to provide “a way for researchers to account for their personal biases and examine the effects…on the data produced” allows a way to cope with these biases, while simultaneously acknowledging that such bias is both inherent and inevitable (Hesse-Biber, 3). I would argue that this intersect between feminist and indigenous studies approach to research biases exposes a problem which is just as evident in Chilisa’s discussion of indigenous research’s four dimensions (13) as it was evident in older western centric research methodologies such as positivism (24-27). Indeed, all of these paradigms make assumptions about the nature of the reality, knowledge, and values of the group or system they are applied to. While I would tend to agree with Chilisa that some assumptions are inevitable in order to be able to conduct structured research of any form, I would call attention to this unspoken issue which seems to lurk around the edges of every discussion about new research methodologies and new research paradigms: as long as the focus is on decolonizing existing research paradigms, or even creating new paradigms within existing narratives in order to meet standard research criteria, is it actually possible to fully legitimize any new research ontology as being wholly unbiased and separate from the oppressive, marginalizing narratives which have come before?

While the above discussion perhaps begins to highlight the importance of intersectionality in research paradigms on forming a multi-faceted understanding of the nature of shared ontologies, it is necessary at this point to properly define what I mean by intersectionality here. Naples and Gurr discuss the origins of feminist intersectionality from a black feminist perspective in the 1980s, focusing particularly on Collin’s emphasis on what intersectional approaches reveal about a “matrix of domination”(Naples and Gurr, 31). However, for the purposes of this discussion I attempt to explore the evolving nature of this definition, as intersectionality has evolved and became key to relating feminist research paradigms to the pursuit of social justice. In particular, this highlights the trend in modern research paradigms towards multi-disciplinary, multi-cultural, multi in general, complex, comparative discussions. This ties into the discussion of feminist standpoint theory, and its assumption that marginalized groups have a “double-vision” which allows them to understand both dominant and marginalized ideologies (Naples and Gurr, 33). I would argue this recalls the inherent biases discussed above in relation to Chilisa’s narrative, in that a certain amount of potentially biased assumptions must first be made in order to determine what constitutes the dominant group and what constitutes the marginalized group(s). In this case, it is necessary to label something in order to analyze it, something which perhaps highlights the potential benefits of developing new Indigenous research paradigms free from preconceived research biases, which focus on the narrative of the colonized other in relation to their own reality, rather than the reality of the colonizer. In other words, attempting to define something without the common, convenient dichotomy of relational us versus them perspectives.

Enke opens the discussion in Transfeminist Perspectives by making a direction connection between feminist and transgender studies, describing the relationality between the two research areas as a “productive and sometimes fraught potential” (Enke, 1). Enke draws a clear connection between gender identity and the nature of reality, by highlighting the individuality of each person’s gender, where “everyone’s gender is made” (1). While this discussion of gender identity is largely predicated on individual identity, something which is perhaps in contrast with some indigenous ontologies, the connection between reality and subjectivity is applicable to both fields. In the case of transgender studies, reality seems to perhaps equal identity, or vice versa. Enke makes the suggestion that trans studies could be viewed as a form of new intersectionality in research paradigms, due in part to the relatively new emergence of the research area. Enke also connects transgender studies to power imbalances, much like early intersectionality paradigms, as trans perspectives are largely viewed as a marginalized other in the larger framework of gender studies narratives. This is arguably most evident in Noble’s discussion of the term cis-gender, and the negative connotations which can be applied to the term (Enke, 58). It is worth noting that the politicization of this term, and the resulting negative connotations, is predicated entirely on how the label is used and applied, rather than the actual word itself.

Video on definition of cis-gender

The commonality seems to run between Indigenous, feminist, and transgender research paradigms in terms of their relation to decolonizing, marginalized, and indigenous narratives. Power relations, a level of oppression, and a utilization for the purposes of social justice connections all of these narratives, tying together the importance of intersectionality between research paradigms.

Image About Intersectionality of oppresion

If you went out and interviewed another five random people on the street, and this time asked them what an intersection was, you would probably still end up soaking wet and possibly detained on suspicion. But you might also have five somewhat similar answers, that for all their differences, might still involve the connections which can grow from the intersection of several different points meeting somewhere in the middle of nowhere, leading to everywhere.

Works Cited:

Links/Images:

“Ontology.” Slideshare.net. IN. http://www.slideshare.net/andrewhinton/context-design-beta2-world-ia-day-2013

Connor O’Keefe. “What Does Cis-Gender Mean?” Online Video Clip. Youtube. Youtube, December 27, 2014. Web. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9AlE-NQWURg

“All Oppression Is Connected.” Rebloggy.com. Tumblr. http://rebloggy.com/post/class-racism-sexism-feminism-capitalism-oppression-privilege-misogyny-socialism/63021736591

Books:

Chilisa, B. “Situating Knowledge Systems.” Indigenous Research Methodologies. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Save Publications, 2012): 1-43.

Enke, A. Finn. “Introduction.” Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014): 1-14.

Enke, Ann. “The education of little cis: Cisgender and the discipline of opposing bodies.” Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014): 60-80.

Frost, Nollaig and Frauke Elichaoff. “Feminist postmodernism, poststructuralism and critical theory.” Feminist Research Practice: A Primer. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014): 43-72.

Hesse-Biber, S. J. “A re-invitation to feminist research.” Feminist Research Practice: A Primer. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014): 1-13.

Munoz, Victor. “Gender/Sovereignty.” Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014): 23-33.

Naples, N. A. & Barbara Gurr. “Feminist empiricism and standpoint theory: Approaches to understanding the social world.” Feminist Research Practice: A Primer. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014): 14-41.

Noble, Bobby. “Trans. Panic: Some Thoughts Towards a Theory of Fundamentalist Feminism.” Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014): 45-59.