In a program like materials engineering, which is both theory- and industry-oriented, undergraduates can be quite bilateral about their future. Some look forward to industry experience, while others may be very enthusiastic about research opportunities. As a former undergraduate researcher and a grad student (and someone who doesn’t like the industry very much), I have been often asked on research opportunities for undergraduates. I only have positives about my own research experience, but that’s often not the case, as I have heard quite a bit of complaints, too. Perhaps I can share my own ideas about undergraduate research opportunities from a few different perspectives.

What do undergraduates want from such experience?

For undergraduates, participating in some research activities is a great opportunity to learn something new and jump out of the textbooks, assignments, lectures which pretty much constitute the “ideal, theoretical” world. It is at least an aspiration.

There are a few pragmatic or vanity motivations though. I will list a few and dissect them in later sections.

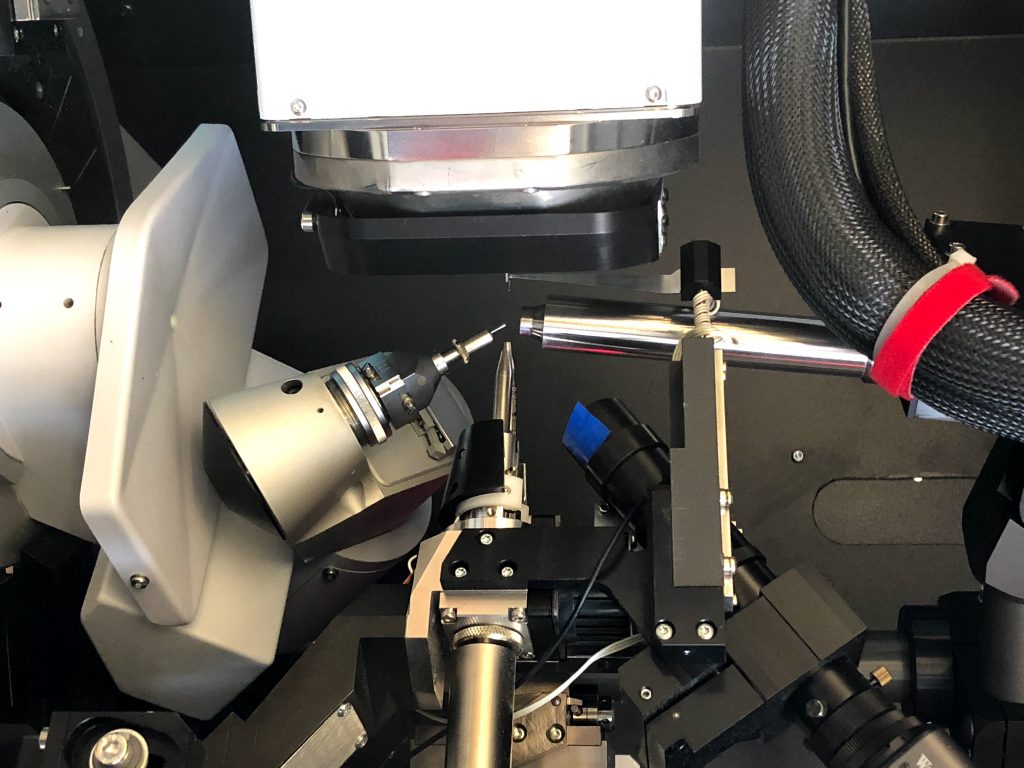

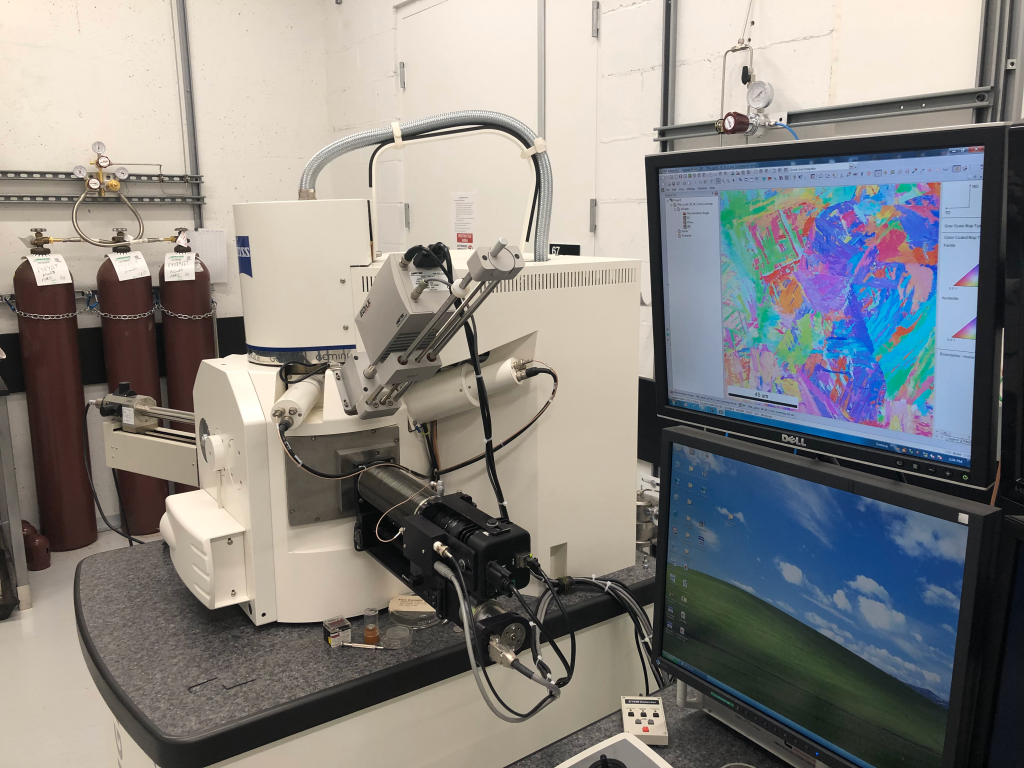

- One of them is obviously showing off. I still remember someone walking into FF319 (computer lab) in lab coats, with a thong in his hand holding a crucible, violating multiple building/lab safety rules. Or things like “I work in AMPEL”, “I touched the SEM”. They do make you feel good when you are a rookie. I am not totally against this, because the first step of every journey is worth celebrating.

SEM is so commonly used in both academic and commercial research that it should be a staple part of the undergraduate curriculum of materials science and engineering.

- Make use of long holidays, so you wouldn’t stay at home for 2-4 months doing nothing. This was one of my motivations of doing summer research as an undergrad.

- Accumulating experience (i.e. things that could turn into entries on your résumé). With research experience ubiquitous among undergraduates, it might me a decided disadvantage if you don’t have it. (Then what separates people if everyone does?)

- Connections & friends.

- Or even more pragmatic, publication opportunities. Quality research experience is a gateway to grad school, and we want to get something out of it. Comparing to understanding of topics, ability to analyze…, a publication entry on your résumé is more tangible (in some communities, publications are an important, if not the only.metric of research ability, which is not true at all). Some supervisors may be kind enough to give you an opportunity (I was a beneficiary), but you should be aware of and be honest about your contribution. You might also get asked about your research in interviews, then having a paper means nothing if you don’t have enough understanding of what you did. If your supervisor don’t want to publish your research , do not push it. There must be reasons behind it. Never attempt to publish without consulting your supervisor first. Your research is likely a subset of a grad student’s work or a patent and that may result in predatory.

- Gain deeper understanding on specific topics. This is not limited to instruments or experimental techniques, but also theories. For example, I worked in a hydrometallurgy research lab and gained quite a lot of knowledge on electrochemistry through reading and guided experiments.

What should you expect as an undergraduate researcher?

The key thing is how we define “research” in this sense.

What we do as research as grad students is probably much broader than undergraduates think. Undergraduates tend to think that research is just working in a lab. Indeed, lab works tend to consist the majority of undergraduate research projects. But it is not the full picture. From my own experience, I summarized the key components of conducting a research project below:

Understand the background of the topic/project. This include reading literature (i.e. get an idea of what is known, what has been done and what is yet to be solved) and, for example, listening to what senior grad students talk during group meetings. This is often omitted or only briefly introduced in undergrad research projects. First, not a lot of undergraduates have the patience to read through the literature (especially as a part-time researcher), and second, the time scope of their project often does not allow them to do so either.

Designing experiments (or models). Again, this sometimes involve learning from the literature. For students with no previous research experience, this can be quite difficult. Sometimes this is taken care of by the supervisor.

Doing experiments (or running models). This might be what undergraduates often define as research and are assigned as their main tasks. It is indeed an integral part of any research project, where you get to touch some cool equipment, and also where the time-consuming, repetitive works tend to stem.

Data processing, interpretation and validation. This is where raw information from the cool equipment is processed (e.g. data, images), transferred to visual elements like plots and charts. Moreover, it should tell you something about the problem you want to solve. One also will validate the results against common sense, established theories and previous works.

Iterations. What if the experiments did not give the desired outcome? Grad students will turn to their supervisors, colleagues and the literature for help, then design new experiments and try again. It is a tough and often inevitable part of grad school. Luckily, most undergraduates don’t have to experience them in their projects.

So as an undergraduate researcher, your task is often simple: experiments and data processing. Sometimes you will also be asked to learn some background knowledge. The most difficult parts are often taken care of by the grad student or the supervisor (professor, research associate, post-doc…). Don’t be disappointed, as these are transferrable skills should you not end up in the research community. Always let the supervisor/grad student know if you desire more challenges. But you should be aware what the bigger, complete picture is.

Thinking experiments as the only component of research is a frequent misunderstanding among undergraduates.

There are, however, certain cases that the grad student ask the student to review the literature (reading papers, textbooks, etc.), and that is where things deviates from the ideal. I am strongly against this type of undergraduate research. It takes a certain level of background knowledge to understand research papers, and undergraduates (especially first- or second-years) tend not to fulfill that requirement. If it becomes merely searching of key words, then the research project is way too menial. Graduate students should actively do these tasks on their own because it’s your own project, your own knowledge network and your own understanding that you are developing. At least at UBC, literature review is a key part of your thesis.

How can we improve the environment for undergraduate research enthusiasts as grad students, etc.?

Try to encourage the students as much as possible. Don’t objectively scare them off.

Try to assign projects to undergraduates with a clear direction.

If possible, try to integrate experiments (or modelling), data processing and interpretation in the tasks.

Be patient and don’t push the undergrad. Be kind to them and try to teach everything you know. It is natural that they will face quite a lot of unfamiliar topics.

Give students chances to present or showcase their work in the form of routine group meetings, etc. An even better idea is to hold a poster/presentation session for all undergraduate research students in the scope of research group or even the department. For example, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences of UBC holds annual poster & presentation sessions for summer students. The students are asked to prepare a poster and an abstract about their research, and then present in front of a crowd. The 2020 edition can be found here: https://pharmsci.ubc.ca/research/summer-student-research-program/2020-virtual-summer-student-research-program-poster

In addition to student direct contacting the supervisor, which should help those with better grades and looking for challenges; there can be such mechanisms organized by student council or the department to pair students with research projects. Such mechanism also exists in UBC MTRL, which was initiated in 2015 and has been implemented for 2 years.

Design and improve courses on characterization techniques, data processing and statistics.

General advice to prospect undergraduate researchers?

Research is not the only career route for STEM major. It is totally fine if you are not interested in research. Don’t force yourself into it.

Ignore the peer pressure. Your friend is working on a more inetresting project or working with a “better” professor? You are jealous of someone? I understand the desire of pursuing higher goals, but at the start of your research career, accumulation of experience and forming your own ideas and plans are more important.

Topic wise, (1) there is no bad topic. People influenced by e.g. The Big Bang Theory may learned the “discrimination” of research subjects. Remember that as an undergraduate, the key is to gain transferrable skills and (primitive) understanding of certain topics. It can be extra motivating to work on an interesting topic, but don’t be too disappointed if you don’t, because you can still learn a lot. Even at the graduate stage and further, remember that all reseach fields are equally important and the ultimate goal is to advance our understanding of the world, and improve our lives. (2) Try to explore more topics at your early stage. Don’t limit yourself a specific one when you are a first- or second-year student (especially if you don’t have a clear favourite topic). Stay curious. You might be interested in topic A now, then change to topic B or C a few months later.

Mineral-related metallurgical research are sometimes not welcomed by undergraduate students because they are “not cool”, despite being an integral part of metal production.

Try to work with different people and groups. People of a research group tends to share similar skill sets, mindsets and knowledge background. It is a vital in the research world to broaden your horizon and get new ideas. Moreover, you should demonstrate to your future supervisor/employer that you are capable of working with a variety of people. This is very important if you want a career in academia.

Asking for opportunities to present your work on group meetings. It will help you practice your presentation, expression and organizational skills. Also a good opportunity to assess the level of your research work.

When possible, read introductory-level textbook of the general topic/experimental technique you are working on. For almost every topic in materials science, there is a classic textbook. Your supervisor should know some of them. Self-learning is a crucial part of grad school and if you want to have a nice transition from undergrad to grad school, you should try it and even form a habit. If you think you have extra energy to burn, you can read more!

Take lab/test notes. Also, take notes when you are doing a new type of experiment, using a new equipment or learning something new in general.

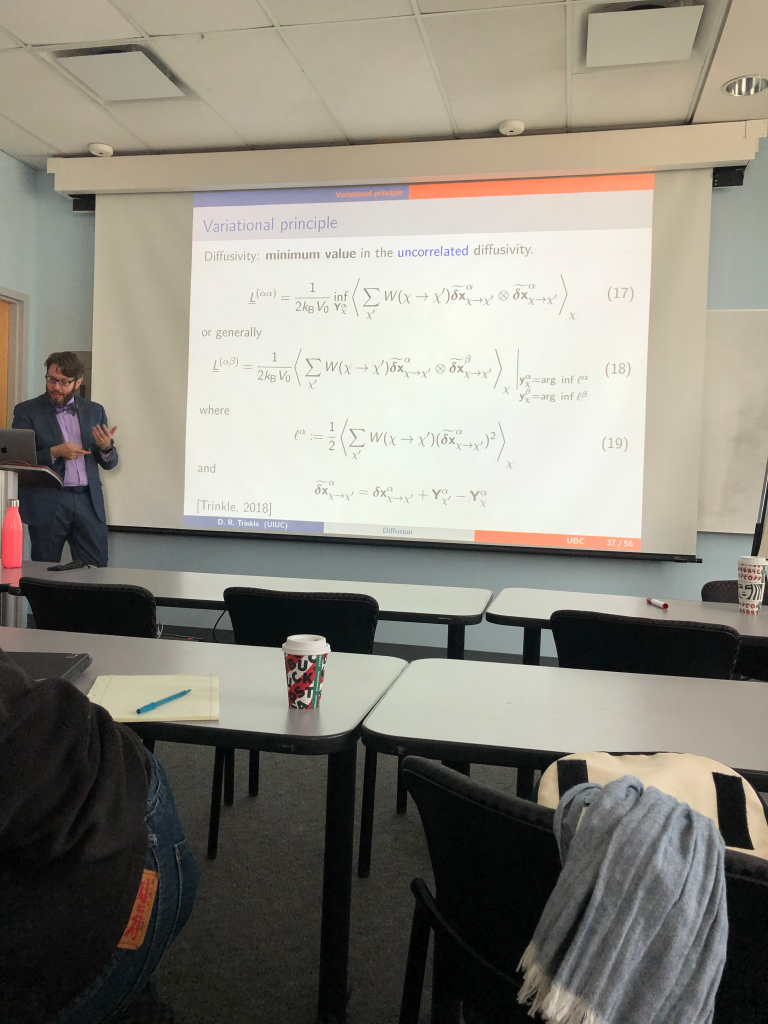

Know your limits. We often hear things like “going outside of the comfort zone”, which can be true. What I want to say here is not to force yourself into doing a lot of works that are beyond your capabilities, because this is only the beginning of a journey, not the final sprint. Further, with limited knowledge it is often not helpful to attending research seminars (if that is a thing in your research group) or lectures that are too advanced. You can easily get lost, waste some time and possibly get discouraged.

Prof. Dallas Trinkle giving a seminar at UBC Materials Engineering in November 2019. Many research seminars are designated for graduate students only and that is with good reasons. Without at least superficial understanding of the topic, one can easily get lost in a convoluted seminar.

Keep a good work ethic. Your grad student supervisor usually don’t expect miracles from you. But you should at least finish the basics and commit a reasonable amount of time and effort.

If your research topic is more or less systematic (e.g.combination background, experiment, data interpretation), try to summarize your research into a scientific report, mimicking the structure of published works. It may not be publishable, but it is a great practice of your scientific writing and definitely transcendents the level of lab reports in your courses.