The northern abalone is a real triple-threatened. No, we don’t mean triple-threat – marine snails don’t sing, they certainly can’t dance with that big fleshy foot, and the main act they’re part of is the Species At Risk Act. Not only are they both beautiful and delicious, but they have a life cycle that’s just about as slow as their locomotion – a trio of traits that has left them threatened with extinction. Their good looks and fine flavour caused them to be severely overfished, and because they take a long time to grow, and need to be nearby other abalones in order to reproduce but take ages to travel, their decimated population hasn’t bounced back in the decades since fishing them became illegal.

What was the Bamfield Huu-ay-aht Community Abalone Project?

So, in 1999, Fisheries and Oceans Canada challenged Canadians to come up with a solution. One such answer was the Bamfield Huu-ay-aht Community Abalone Project, a hatchery release program that operated out of a tiny town on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. This partnership between the Huu-ay-aht First Nation, Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, scientists and community members was a conservation project, for the most part, but it did incorporate some community and economic aspects as well. The project was quite community-oriented, looking to provide employment and attract economic activity to Bamfield. Hatchery-raised abalone were planned to be sold to restaurants to supplement project funding, although changes to the rules surrounding the trade and harvest of abalone put a damper on that aspect of the project. To meet their goals of abalone conservation, wild-caught abalone were used to make abalone to be raised in the hatchery, which would then be released into the wild, either as larvae, which float in the water column, or juveniles, which stay on the bottom.

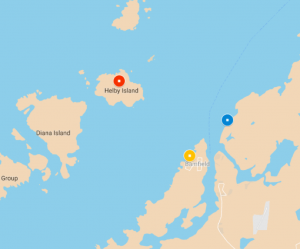

Map of Vancouver Island showing the location of Bamfield. Made in R.

Why focus on northern abalone?

The northern abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana), an endangered species according to the IUCN Red List, is only found along the Pacific coast of North America, and the only abalone species commonly found in British Columbia. It feeds on algae, and is preyed upon by sea otters. Abalone face threats of illegal harvesting and multiple other ocean predators. Abalone are naturally slow moving and need to be within 1 metre of each other in order to spawn, so after their population decreased due to overfishing and the remaining abalone were spread out, it became incredibly difficult for them to reproduce. This species is a slow growing species as well so it will take a long time for the abalone to mature. This combination of predators, natural issues with spawning and slow growth makes it very challenging for abalone populations to recover once they are depleted, and some scientists believe that species such as the northern abalone are in need of human intervention to persist.

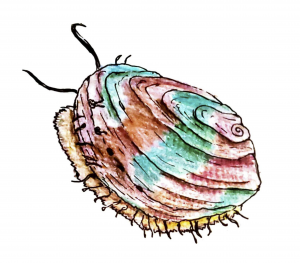

An illustration of the northern abalone (Haliotis kamtschkana). The cryptic colouring of the shell makes them difficult to spot, but the inner coating is iridescent like a pearl.

Northern abalone are a species of great significance on British Columbia’s coast, having served their role as a traditional food source for the coastal First Nations. The Huu-ay-aht nation’s name for the abalone is ؟apsy’in, and they have traditionally harvested abalone for food, as well as for cultural and ceremonial uses. The interior of the shell is coated with mother-of-pearl, giving it a unique iridescent quality. The shells have traditionally been used as jewelry, or carved for other decorative uses. Both the meat and shells of the abalone are popular in Asia, and trans-Pacific trade of abalone species goes back over a century. Even as fisheries for the different species of abalone close or are restricted, illegal fishing to meet international demand remains a threat.

Was the project successful?

The Bamfield Huu-ay-aht Community Abalone Project defined success by the number of individuals they were able to release into the wild. From that point of view, this project was in fact a success, as it released millions of larvae and juvenile abalone into the waters around Bamfield.

Map of Bamfield showing abalone out-planting locations: Red-Helby Island, Blue-Goby Town, Yellow-Scott’s Bay

However, the number of abalone released really only lets us look at hatchery or breeding program success, and not at the success of the project from a conservation standpoint. For that, we need to look at the abalone populations after hatchery releases. In places where abalone were released from the hatchery there still aren’t enough abalone for reproductive success. Around a quarter of samples were hatchery-raised individuals, far lower than the almost 50% found from Japanese hatcheries. This means that the survival rate for hatchery-raised abalone must be quite low; illegal fishing and predators like sea otters, starfish, and crabs, threaten these younger abalone as they are released into the wild.

The veliger larva form of the northern abalone. It settles quite quickly out of the water column, so abalone density increases dramatically right after release events.

While abalone populations show some signs of recovery, it is unclear what role BHCAP has played in this success. In the places where the BHCAP did release individuals, there still aren’t enough abalone to ensure reproductive success. From a conservation standpoint, then, we cannot say that this project was a success. Perhaps if the project had more sound financials, and was able to continue for a longer period of time, then it could have yielded results, since abalone are such long-lived animals.

How does this inform future projects?

Though there was an a change in the law that made the Bamfield project a financial failure, it does highlight the fact that without funding even the best conservation projects ever invented will fail. The idea of coming up with a plan for programs to fund themselves is a good way to allow conservation projects to progress and continue without outside funding. This can stop having someone looking over the shoulder of a program at all times.

Abalone are hard to spot in the wild, making it hard to estimate population size.

The Bamfield project also highlighted the fact that community engagement is must. Making sure that the people around the project are invested in its success will keep commitment to any program. If the community is not considered when planning a project what reason would they have help out when it gets started?

Projects need to have methods to measure their success. Creating some kind of measurement, a metric, is vital to find out if a project is working. Bamfield decided their metric was the number of abalone they could introduce back into the wild. Whilst this is a good metric of their output, they did not measure how many abalone survived. For other projects in future, using a metric that includes long-term survival can help determine what the impact the project has on the ecosystem at large.