Today in class, Professor Nagarajan asked which historical event launched the personal computer. My ears perked up, and my hand shot straight in the air. As a self-proclaimed history buff, any mention war peaks my interest. When he finally called on me, I blurted, “WWII”, and sat back to hear the story.

To my surprise, he did not recount the narrative of IBM and the Holocaust, but instead chose to say that the PC was developed when IBM decided to aid the American war effort. I argue that the roots of the development of the personal computer were embedded within the machines that IBM produced to help facilitate the Holocaust. But I digress. For this post, I will concentrate on the relationship between IBM and the Holocaust (and not argue which side of WWII forged the development of the PC), as it ties the September 11th class on business ethics nicely to today’s class on operations.

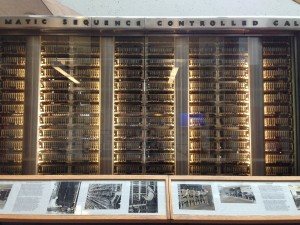

IBM made the Holocaust incredibly efficient. Hitler was a diligent record keeper, and instead of going through the painful process of manually inputting entries, the solutions company managed to isolate and identify the Jewish population with unprecedented speed and precision, through automation. Dehomag, a subsidiary of IBM, compiled a census of Prussians, recording their ancestral information on a punch card. The information from these cards was then computed and sorted by IBM’s machines (a precursor to the computer) at a rate of 250, 000 cards per hour.

IBM helped identify and record the Jewish population in a nation-wide census, helped ensure the trains to the camps ran on time through automating the process, and helped organize the camp labour.

It is true that the Holocaust would have happened regardless of IBM’s participation. But IBM made the operation more efficient, and dramatically increased the scale of the massacre. In order to increase profit, Dehomag (and by consequence, IBM) disregarded morality; Dehomag crossed the unethical line. It must have been fairly simple to refuse to help the Nazis; in major cities, Americans were protesting and boycotting anyone who did business with the German government. Yet, the temptation of profit lured IBM to engage in business overseas, in secret. In fact, the press did not manage to make the connection between the company and the Third Reich. Internal memos of the company were even “encrypted”. The language is almost indecipherable to an outsider.

///If you are interested in this narrative, and in how IBM’s involvement was finally revealed, I would encourage you to read “IBM and the Holocaust” by Edwin Black. It can be quite dry, but the information is worth the time.///