The Garden of Perfect Brightness

Much like the collections of colonial trophies in the Crystal Palace in London or the grounds of Versailles, the Yuanmingyuan in Beijing was a complex which housed an array of foreign objects, artwork, pleasure gardens and architecture expressing the Qianlong emperor’s political power.¹ The resulting collection of foreign treasures were symptomatic of a common imperial desire to exercise power over a far-reaching global domain, summarized within the contents of a contained landscape. Yuanmingyuan was constructed following an imperial logic of control and heterotopia, exercised through the seen image. The image was the primary means of expressing and understanding imperial power, by illustrating the fantasy of collecting all exotic treasures of the world under one domain. The image of the Yuanmingyuan, therefore, became a source for European understandings of Chinese aesthetics and ultimately defined the cultural weight of its destruction by imperial Europe at the end of the Opium war.

¹“Garden of Perfect Brightness” (Yuanmingyuan). Govt.Chinadaily.com.cn. August 16, 2019. <https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/201908/16/WS5d562394498ebcb1905787cf/garden-of-perfect-brightness-yuanming-yuan.html>

All under heaven: The heterotopia of empire

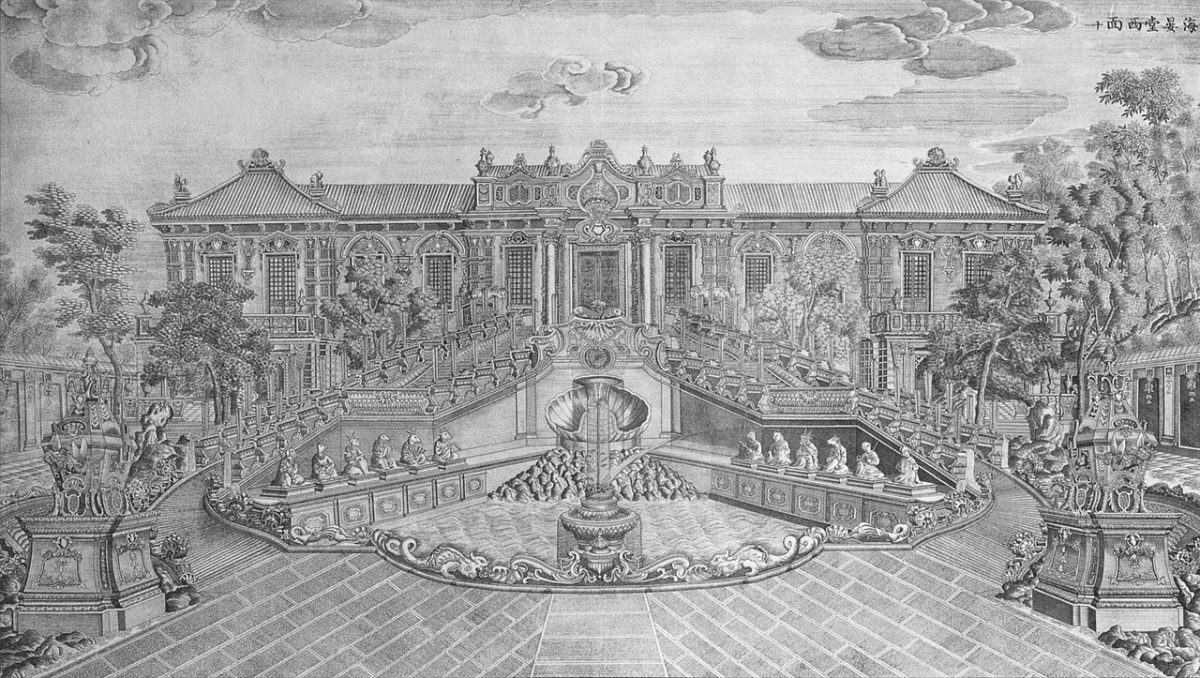

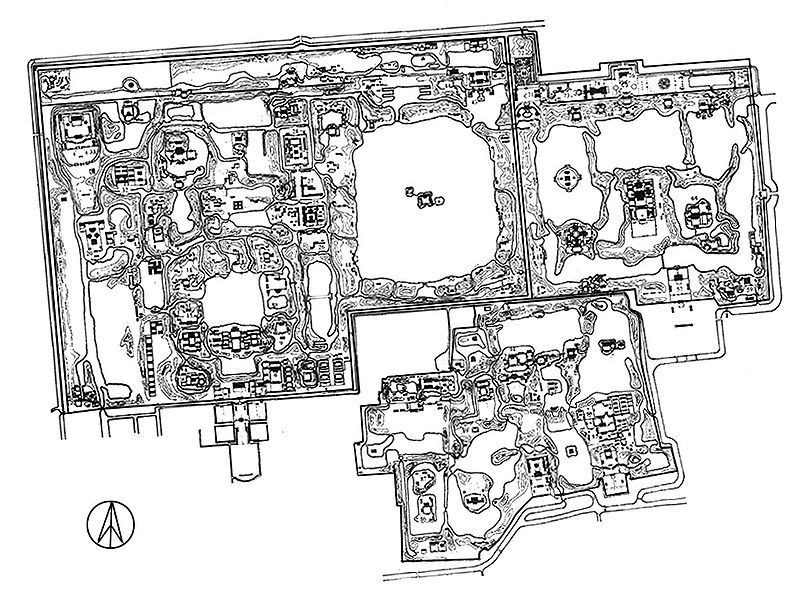

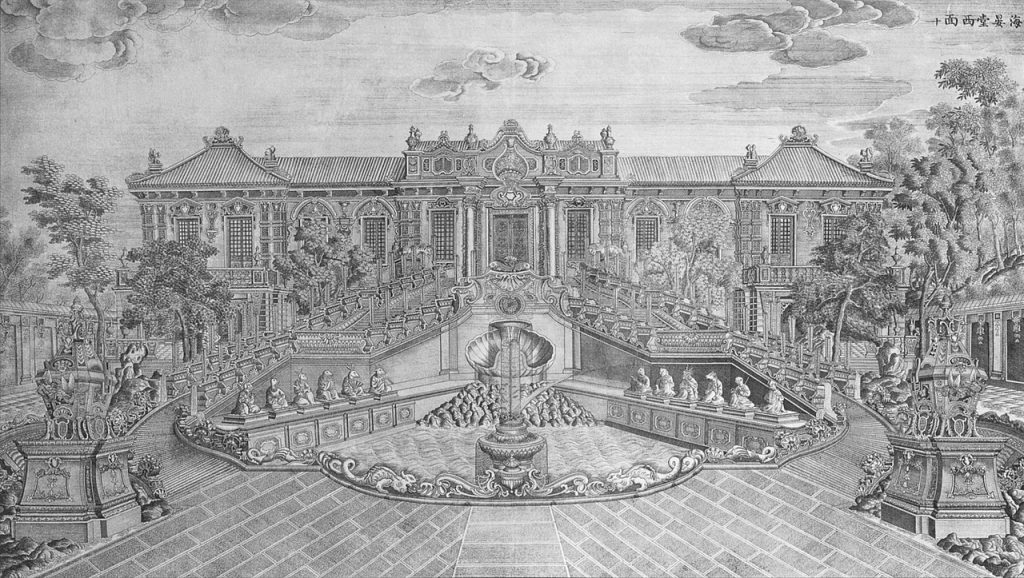

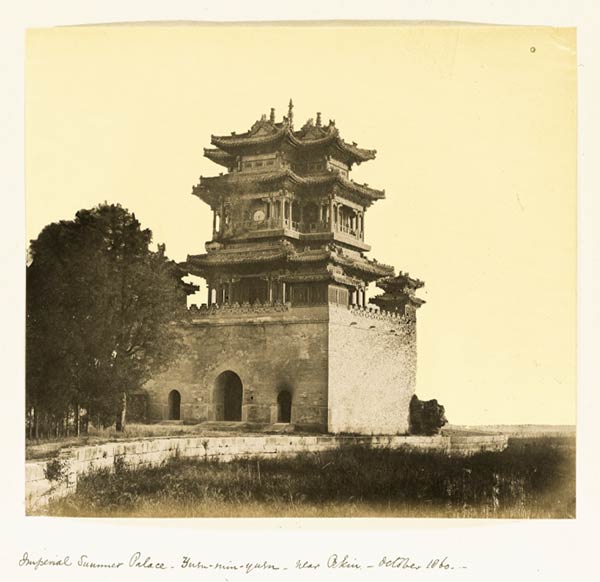

The Yuanmingyuan complex, constructed from the 16th to 18th century, held over a thousand structures and encompassed 860 acres: It served primarily as a summer resort for the Qinglong emperor, many of its spaces created for leisure.² Inside the imperial gardens, the emperor collected buildings and trinkets from all over the world, including Europe, Asia and distant regions within China. Among these included Mongolian and Tibetan temples, European palaces and neoclassical architecture, and gardens drawn from Hangzhou and Suzhou. ³ The Xiyanglou, literally translating into “Western-style building”, were a collection of palaces, gardens and a maze in an area of the complex that incorporated European styles, most notably the le notre style that was popular in Europe at the time. ⁴ One of these included the Haiyantang, a hall built in a highly decorated French neoclassical style: Its entry was embellished with a seashell-shaped fountain and two grand sweeping staircases, combined with the twin classical columns of the French nationalist style.

In addition to collecting spectacles from foreign countries, the emperor aspired to collect aspects of the world that were inaccessible to nobility. Among the gardens was also an artificial market town, comparable to the busiest commercial street in Beijing at the time. The market town was a place of leisure where the emperor would visit with his entourage, browsing shops and stalls staffed by eunuchs acting as shopowners. Palace ladies acted the part of customers,, while others played even the roles of beggars, thieves, sightseers and minstrels. Another area was set aside as an acting farm, with fields, farm animals and equipment.⁵ Like the construction of the Xiyanglou, the emperor’s mock market and farm were symptomatic of an imperial desire to symbolically collect all aspects of an empire under a single roof, or tianxia, “all under heaven”. ⁶ Haiyan Lee discusses this imperial desire in relation to Foucault’s heterotopia: A heterotopia is one place that encapsulates all other real places within a culture and places them together, where they are simultaneously represented, altered and in conflict. The heterotopia exists in the institution of society, and lies outside of all of the places that it subsumes.⁶ Yuanmingyuan and many similar imperial complexes such as the 1851 London exhibition’s Crystal Palace collect culture in such a manner, striving to collect visual tokens of knowledge or conquest, to demonstrate the grand reach and authority of a body of power. Yuanmingyuan in particular aspired to attain a state of utopia, where all places in the Manchu empire and Western oceans were called together into a small microcosm of the world.

² “Garden of Perfect Brightness” (Yuanmingyuan). Govt.Chinadaily.com.cn.

³ Erik Ringmar. “Malice in Wonderland: Dreams of the Orient and the Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China.” Journal of World History 22, no. 2 (2011): 273-98. Accessed February 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23011712. 277

⁴ “Western-Style Palaces”. Govt.Chinadaily.com.cn. August 16, 2019. <https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/201912/23/WS5e007fb6498e1ed196a6b620/western-style-palaces.html>

⁵ Haiyan Lee. “The Ruins of Yuanmingyuan: Or, How to Enjoy a National Wound.” Modern China 35, no. 2 (2009): 155-90. Accessed February 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27746912. 173

⁶ ibid. 160

⁷ ibid. 159

The self-image of Yuanmingyuan

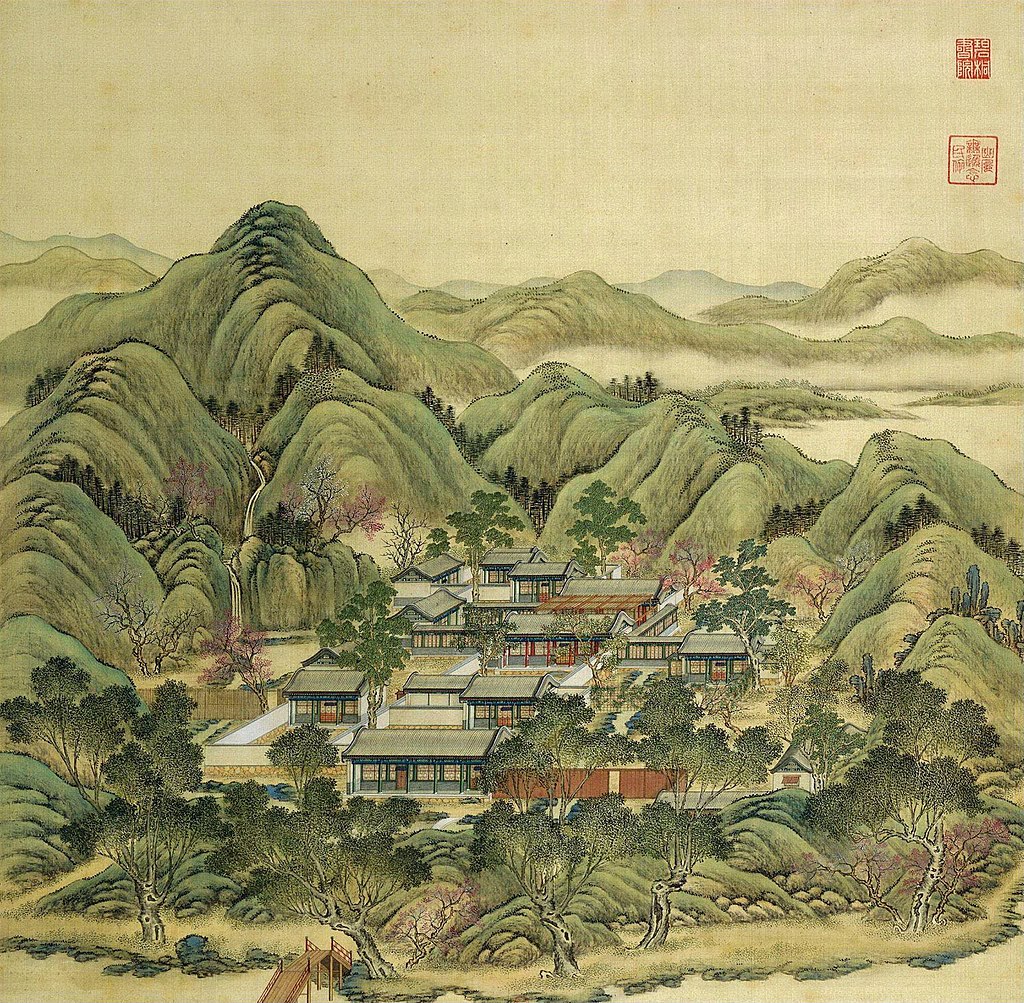

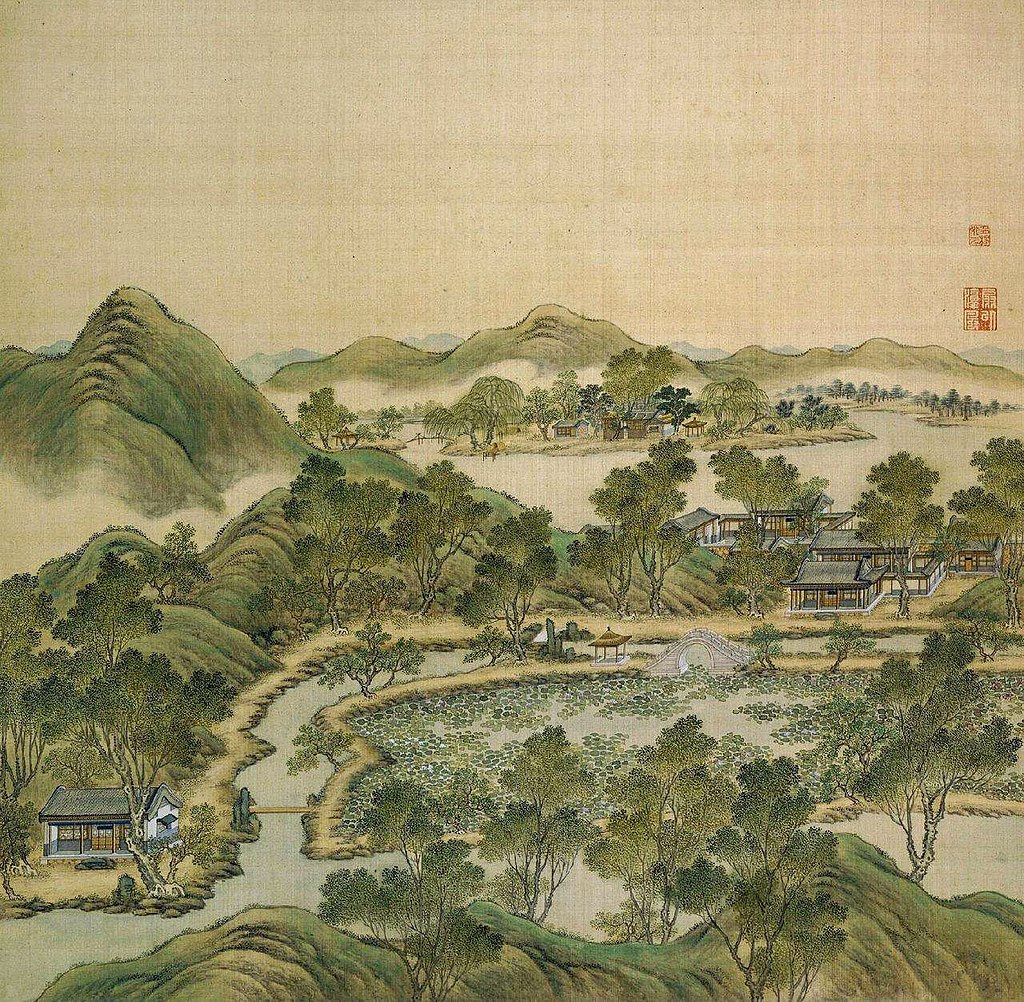

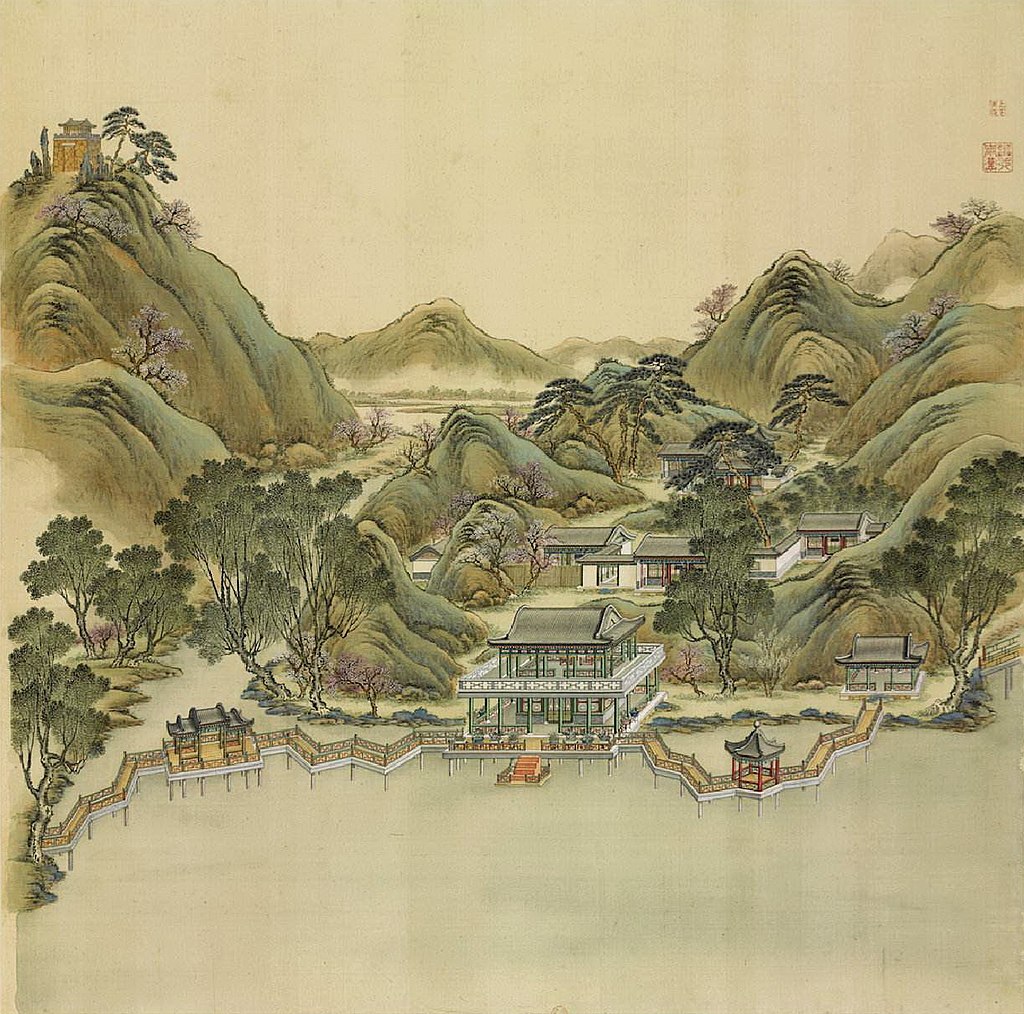

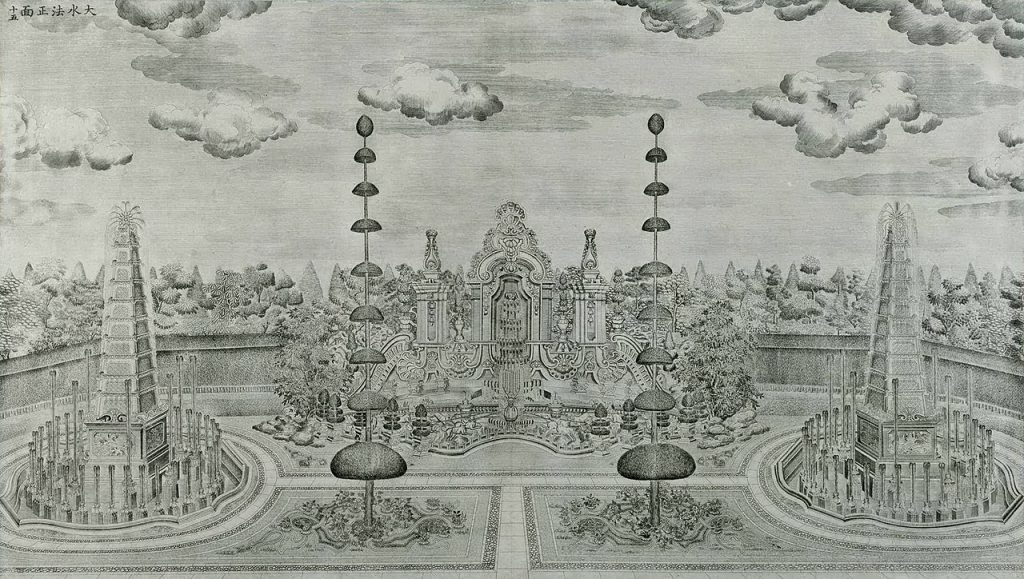

The amalgamation of the exotic at Yuanmingyuan was a mechanism for constructing imperial Beijing’s self-image. The image, embodied in forms from paintings to landscape views, is an effective means of exercising power in its ability to dispatch narratives associated with the physical form of a project and the empire’s self identity. Among its 2-dimensional representations, Yuanmingyuan is most known for a set of 20 copper engravings of the European-style Xiyanglou, and a collection of 40 paintings spanning the entire complex done by order of the emperor.

Over 200 copies of the 20 engravings were preserved within the complex, while others were given as gifts to guests and connections of the imperial court. The engravings offered the clearest depictions of the Xiyanglou’s western style facades and gardens.⁸ Copies were made easily, allowing individuals to perceive the garden’s grandeur far beyond the geographical reaches of Beijing.⁹ Meanwhile, the “40 Views of the Yuanmingyuan” served as wooden covers to pieces of poetry on the complex’s scenery, composed by the emperor.¹⁰ Each view was chosen to highlight views of particular note, playing into the principles of the picturesque garden. The painting style, just as the rest of Yuanmingyuan, was rendered in a blend of Chinese and European methods.¹¹

The 40 Views were preparatory work for one comprehensive schematic map of the entire Yuanmingyuan complex upon completion. This painting would have measured over 386 by 277cm in size, and was painted in a hybrid Sino-European style.¹² Just as the British picturesque garden, with its expansive pastoral views, is a medium for exercising power over the land and the cultures of exotic artifacts on display, the gardens and paintings of Yuanmingyuan were mediums of asserting imperial authority through the viewable image. The views that are presented to the occupants of Yuanmingyuan is one of infinite dominion, giving the eye a composition where the empire appears the surpass the horizon. The comprehensive map of all of these views illustrated Yuanmingyuan as a self-contained heterotopia, through which the emperor may survey his entire miniature global domain.

⁸ Vimalin Rujivacharakul. “How to Map Ruins: Yuanming Yuan Archives and Chinese Architectural History.” Getty Research Journal 4 (2012): 91–108. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1086/grj.4.41413134

⁹ Marcia Reed. The Qianlong Emperor’s copperplate engravings. Harvard Library Bulletin 28 (1), Spring 2017: 1-24.

¹⁰ John Finlay. “40 Views of the Yuanming yuan: Image and Ideology in a Qianlong Imperial Album of Poetry and Paintings.” PhD diss. 2011. Yale University.

¹¹ Seo Yoonjung. “A New Way of Seeing: Commercial Paintings and Prints from China and European Painting Techniques in Late Chosŏn Court Painting.” Acta Koreana 22, no. 1 (06, 2019): 61-87. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.18399/acta.2019.22.1.004.

¹² Finlay. 19

Letters to Europe and the Chinoiserie fantasy

Yuanmingyuan’s image, as it was communicated by Jesuit correspondence, guided the development of European attitudes towards Chinese aesthetics. Its imperial identity eventually contributed towards the ideological prominence of its destruction and looting in 1860.

The outward communication of Yuanmingyuan’s imperial constructions was largely facilitated by French Jesuit missionaries who served the Qianlong emperor in the late 18th century, who were responsible for major cultural exchanges between imperial Beijing and Europe during this time.

The missionaries built a relationship with the emperor as part of a top-down process of spreading Christianity: They aimed to convert more people by first gaining the favour of the imperial court, through providing records of and reproducing European technology, architecture, art and music for the court.¹³

Jesuit correspondence with France took the form of the lettres édifiantes et curieuses, which included detailed accounts of the emperor’s palaces and gardens. These letters provided Europe with what was considered the most reliable information on China in the 17th and 18th centuries, and fed directly into the European understanding of imperial China. Perhaps one of the most influential letters was one by the court painter Jean Denis Attiret in 1745, describing the luxury and beauty of the Qianlong emperor’s heterotopic paradise.¹⁴ The wondrous multiplicity of Yuanmingyuan’s architecture and landscape was evidence of the emperor’s absolute rule: It encapsulated the variety of exotic plants, animals, technology and cities of “times past and times future” (Ringmar, 278)¹⁵. Attiret further provided detailed accounts of Chinese gardens, and their employment of irregularity, meandering paths and surprising, enchanting vistas that revealed themselves to the viewer as they walked.

Attiret’s captivating letter fit well into the preexisting chinoiserie fashion in Europe, where it inspired the creation of Chinese-style architecture and gardens. However, this fashionable attitude peaked in the 1740’s and turned to disdain by the 1790’s, as Chinese styles were viewed as vulgar and overbearing in the eyes of the neoclassical man. Even as Chinese art was decried for being too feminine and undecipherable, lacking order and threatening the sanctity of rationality and intelligence, English gardens continued to employ the meandering and irregular forms of the picturesque Chinese aesthetic.¹⁶ The image of Yuanmingyuan persisted through the medium of landscape: Even while the neoclassical understanding of Yuanmingyuan discredited it as immoral and inferior, the fantastical heterotopia of the palace’s grounds remained in the picturesque gardens and imaginations of the European mind.

¹³ Erik Ringmar. “Malice in Wonderland: Dreams of the Orient and the Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China.” Journal of World History 22, no. 2 (2011): 273-98. Accessed February 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23011712.

¹⁴ ibid. 277

¹⁵ ibid. 278

¹⁶ ibid. 284-286

1860 Destruction

It was this image of Yuanmingyuan’s heterotopia, and its expression of empire through the image of total dominion, that made its destruction in 1860 an imperial act at the hands of Britain and France. As a definitive end to the second Opium war, British and French troops invaded Yuanmingyuan and looted the complex of its artwork, finishings, valuables and artifacts: The remainder was burnt and destroyed. This invasion demonstrated an attitude where by destroying the heterotopic, imperial demonstrations of another authority, European imperial forces could assert their supremacy as an uncontested imperial power. Garnet Wolsely, a British officer present in the destruction of Yuanmingyuan, wrote:

“The destruction of the emperor’s palace was the strongest proof of our superior strength; it served to undeceive all Chinamen in their absurd conviction of their monarch’s universal sovereignty.” (Wolseley, Garnet. 1862)¹⁷

Items taken during the looting of Yuanmingyuan, such as an imperial throne, were funneled towards the residences of English and French monarchs, many of them ironically gifts that had been given from the monarchs to the Qianlong emperor.¹⁸ Prominent paintings and engravings of Yuanmingyuan, largely the emperor’s own personal representations of the complex, were also taken as part of imperial plunder. The album of poetry and illustrations of the 40 Views of Yuanmingyuan were stolen by French troops and held at the French National Library, where they remained well into present day.¹⁹This violent acquisition of the painted image is a direct demonstration of the attack on the imperial authority of the emperor, even more so than the theft of 3-dimensional artifacts. The 40 Views of Yuanmingyuan, along with the comprehensive map of the grounds, were expressions of authority belonging to the emperor personally, and served as memorialized evidence of the emperor’s power on a global scale. European ownership of the image of Yuanmingyuan, therefore, holds a symbolic meaning that surpasses the physical destruction of the buildings and gardens.

¹⁷ Wolseley, Garnet. Narrative of the War with China in i860; to Which Is Added the Account of a Short Residence with the Tai-Ping Rebels at Nankin and a Voyage from Thence to Hankow. London: Longman, Green, Long man, and Robe, 1862.

¹⁸ Weatherley, Robert and Zhang, Qiang. “The Tragedy of Yuanmingyuan,” in Aggressive Nationalism: Utilising the Yuanmingyuan Incident (Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge, 2017)

¹⁹ Finlay. 37

Conclusion

Had the image of Yuanmingyuan been less marvelous in the eyes of the European troops, its destruction would not have had the same cultural weight.²⁰ By absorbing and devaluing Chinese aesthetics as they were presented by the fantastical letters from Beijing’s French Jesuits, and then ultimately destroying the icon of Beijing’s imperial prowess, European forces were able to redefine and dominate a threat to their universal dominion. The heterotopia of Yuanmingyuan, represented and understood through its picturesque and two dimensional image, established the complex as a symbol of Chinese imperialism. The notion of the picturesque and heterotopic were characteristics of empire that resonated with those of European imperial powers, ultimately setting the Yuanmingyuan as a target for the assertion of European imperialism on a global stage.

²⁰ Ringmar. 293-294

Bibliography

Finlay, John. “40 Views of the Yuanming yuan: Image and Ideology in a Qianlong Imperial Album of Poetry and Paintings.” PhD diss. 2011. Yale University.

“Garden of Perfect Brightness” (Yuanmingyuan). Govt.Chinadaily.com.cn. August 16, 2019. <https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/201908/16/WS5d562394498ebcb1905787cf/garden-of-perfect-brightness-yuanming-yuan.html>

Lee, Haiyan. “The Ruins of Yuanmingyuan: Or, How to Enjoy a National Wound.” Modern China 35, no. 2 (2009): 155-90. Accessed February 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27746912.

Reed, Marcia. The Qianlong Emperor’s copperplate engravings. Harvard Library Bulletin 28 (1), Spring 2017: 1-24.

Ringmar, Erik. “Malice in Wonderland: Dreams of the Orient and the Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China.” Journal of World History 22, no. 2 (2011): 273-98. Accessed February 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23011712.

Rujivacharakul, Vimalin. “How to Map Ruins: Yuanming Yuan Archives and Chinese Architectural History.” Getty Research Journal 4 (2012): 91–108. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1086/grj.4.41413134

Weatherley, Robert and Zhang, Qiang. “The Tragedy of Yuanmingyuan,” in Aggressive Nationalism: Utilising the Yuanmingyuan Incident (Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge, 2017)

“Western-Style Palaces”. Govt.Chinadaily.com.cn. August 16, 2019. <https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/201912/23/WS5e007fb6498e1ed196a6b620/western-style-palaces.html>

Wolseley, Garnet. Narrative of the War with China in i860; to Which Is Added the Account of a Short Residence with the Tai-Ping Rebels at Nankin and a Voyage from Thence to Hankow. London: Longman, Green, Long man, and Robe, 1862.

Yoonjung, Seo. “A New Way of Seeing: Commercial Paintings and Prints from China and European Painting Techniques in Late Chosŏn Court Painting.” Acta Koreana 22, no. 1 (06, 2019): 61-87. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.18399/acta.2019.22.1.004.

Images

Fig.1: Plan of the Old Summer Palace. Public Domain. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yuanmingyuan_plan.jpg>

Fig.2: Haiyantang. Public Domain. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=333024>

Fig.3: Shen Yuan, Tangdai, Wang Youdun. Green Wutong Tree Academy. <http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/garden_perfect_brightness/ymy1_essay03.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25049559>

Fig.4: Shen Yuan, Tangdai, Wang Youdun. Crops as Beautiful as the Clouds. <http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/garden_perfect_brightness/ymy1_essay03.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25049584>

Fig. 5: Shen Yuan, Tangdai, Wang Youdun. Heavenly Light Above and Below. <http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/garden_perfect_brightness/ymy1_essay03.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25049561>

Fig. 6: Jesuits. Letters from missions; Le Gobien, Charles, 1653-1708; Querbeuf, Yves Mathurin Marie Tréaudet de, 1726-1797

Fig.7: 清宫廷画师绘制,造办处工匠雕版.A set of twenty depicting the Xiyanglou in the Old Summer Palace, 1786, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=333019

Fig.8: Felice Beato and German Ernst Ohlmer. Yuanmingyuan. 1860 <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2016-09/19/content_26827933_2.htm>

Fig.9: Felice Beato and German Ernst Ohlmer. Yuanmingyuan. 1860 <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2016-09/19/content_26827933_2.htm>Fig.10: Felice Beato and German Ernst Ohlmer. Yuanmingyuan. 1860 <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2016-09/19/content_26827933_2.htm>