The Fall of the Tokugawa Era and the Rise of Imperial Japan

The tail-end of 19th century Japan saw a major transition of authoritative power that sparked a new era of rule throughout the nation. In 1868, Emperor Mutsuhito, later known by his reign name Meiji, and his Imperial forces recognized the fragile rule of the Tokugawa regime and overthrew their power at the political center of the nation, Edo, now known as modern-day Tokyo. The Tokugawa Period (1603-1867) was a military dictatorship consisting of Japan’s samurai class, or shoguns, that assumed power over the Emperor and ruled Japan for over 250 years. Leading up to their fall during the Boshin War of 1867, the shoguns experienced detrimental financial strain as castle maintenance throughout their empire became a burden on the overall regime1. Moreover, the reliance of these traditional castle reflected a lack of faith in military competence of the samurai, leading to internal political and social unrest. As a result, the Tokugawa’s commitment to traditional castles also meant a commitment to the symbol of a feudal past. Beginning from the south-west of the Imperial capital of Kyoto, the Emperor’s military exerted their superior forces upon numerous shogun castles until arriving at the Tokugawa’s capital of Edo. Overwhelmed by the Imperial army, the Boshin War ultimately decided the surrender of the Edo Castle of the shogun’s and thus the fall of the Tokugawa began simultaneously with the Rise of the young Emperor Meiji. The early view that castles were primarily symbols of authority with little or no practical purposes was deeply rooted in Tokugawa precedents. For the Emperor, and in-turn Imperial power, the transition of the Edo Castle into the Imperial Castle entailed the appropriation and redefining Japan’s heritage of the shogun’s dynasty into a new modern nation. The design of the new Imperial Castle was instrumental in the nation casting off its feudal past that allowed the nation to transition into a new era of civilization and enlightenment.

1Oleg Benesch. Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 28, 2018, pp 107-134.

Edo and the Way of the Warrior: Bushido

The Edo Castle was the largest castle in Japan during the Tokugawa rule and its city was built from the core outwards. This meant that the castle was the nucleus of the city while the dense urban fabric radiated outwards towards beyond the city’s limits (figure 1). Edo did not have a perimeter wall which meant that its surrounding context of winding streets, close neighbourhoods and moats consisting of warriors, merchants, peasants, and farmers acted as the city’s defense for external attacks. This was a strict ideology of the Tokugawa rule: the way of the warrior, known as the bushido. Late 19th century architectural historians Orui Noboru and Toba Masao described the castles of the Tokugawa era as made to be expressive of fearless composure of mind, invincible fortitude, and unshaken faith – the qualities representing the noblest mind and highest spirit of the samurai2. There was a clear link between the Tokugawa castles and the ideology of the bushido, but especially crucial within the shogun’s headquarters of the Edo Castle. Given its unique location was critical that this ideology extended to the daily lives of the city’s residents. Architect Furukawa Shigeharu also argued that Japanese castles were the background for and an extension of the bushido spirit and that these ideals must flow beyond castle walls and into each of the nation’s citizens3. Interestingly, the fall of the Tokugawa rendered the meaning of the bushido problematic as numerous castles were inevitably taken by Imperial forces and ultimately the Edo Castle, the national core of the way of the warrior. As a result, the conquering of Edo Castle was the conquering of the idea of the bushido and therefore an opportunity for the Emperor his Imperial loyalists to redefine its meaning through the new Imperial Castle.

2Orui Noboru and Toba Masao, Castles in Japan, Tourist Library, (Tokyo, 1935), pp 72-73.

3Oleg Benesch. Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 28, 2018, pp. 107–134.

From Edo to Imperial

This idea of the bushido became integral in the Emperor’s design of the Imperial Castle in 1888. Rather than prescribing bushido with historic Tokugawa ideology, the Imperial Castle was an opportunity to redefine the bushido and separate it from its feudal precedents of the Tokugawa castles. The way of the warrior should not reflect a military dictatorship but rather exhibit a unified nation of peace and solidarity through the Meiji Restoration of the Imperial Castle. Rather than military association, the Imperial Castle reflected a new era of union and civilization through values borrowed from the West. The momentous transformation of the Imperial Castle occurred during the Fall of 1888, designed by Japanese architect Katayama Tokuma4. Tokuma was trained by British architectural professor Josiah Conder who was recruited by the Imperial Government to teach architecture at the Imperial College of Engineering in 1876. The Imperial government recognized his talents after winning the Soane Medallion in Britain a few years prior; a prestigious architecture award for his work. Through his work and many oligarchs that ventured to the West, the Meiji government, especially the Emperor, began to understand Western architectural models were a symbol of a new era that would demonstrate Japan’s modernity. Conder’s admirations for indigenous Japanese architecture along with his teachings of imposing neo-classical and Baroque interventions allowed his pupil Tokuma to apply these methods upon the Imperial Castle5.

4Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 76–80.

5Olive Checkland, Japan and Britain after 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015, pp. 73–82.

The Design of the Imperial Castle

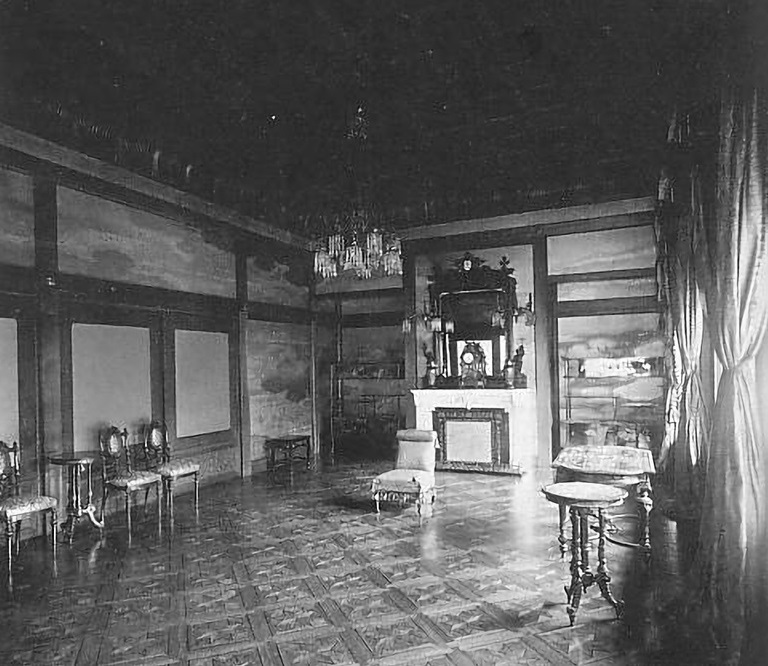

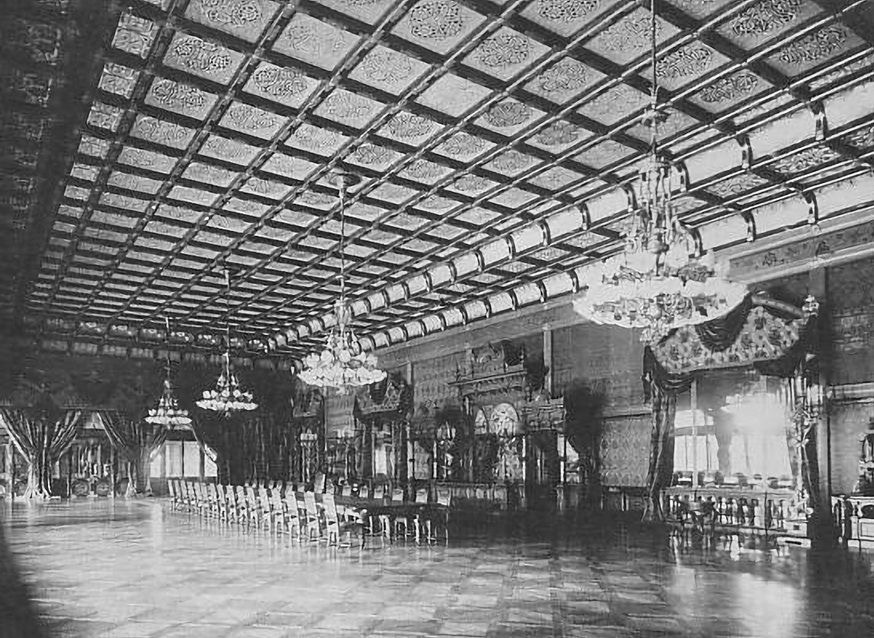

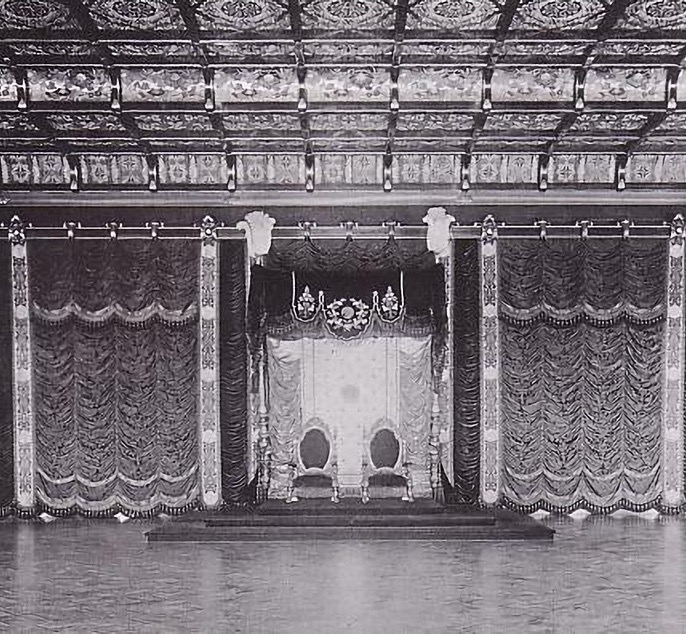

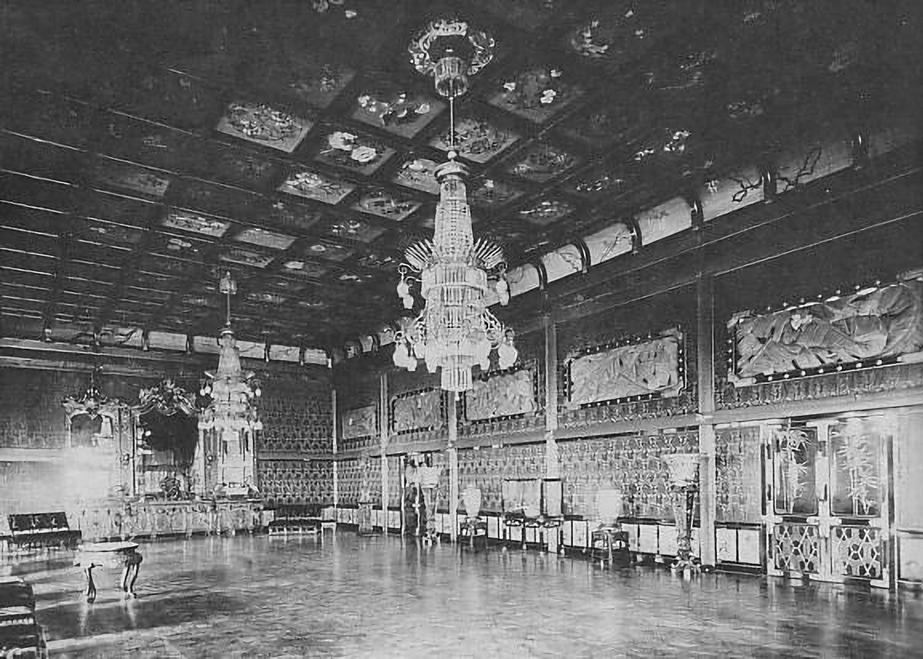

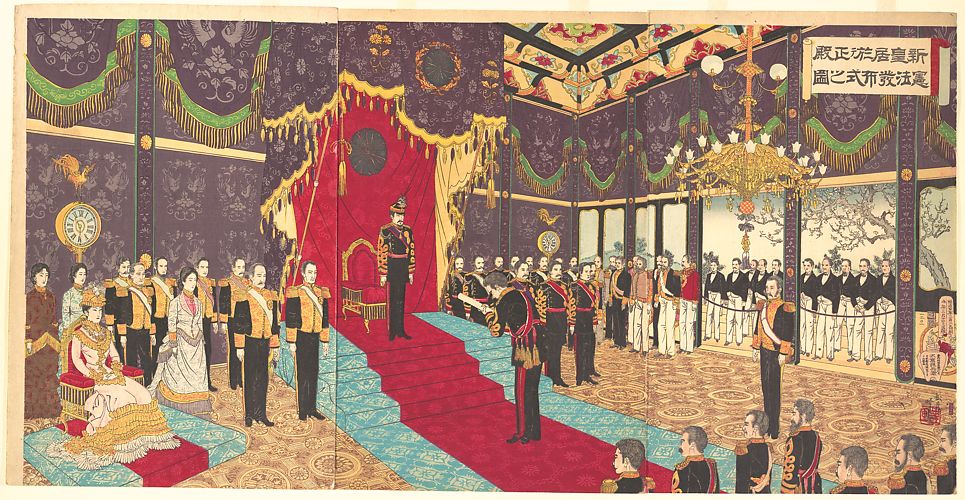

The Office of Palace Construction, the committee responsible for constructing the new Imperial Castle, employed Tokuma for its new design. However, prior to his designs, he was sent to various parts of Europe to consider the Western’s architectural styles as well as interior furnishings and decoration. France became an inspiration for him and was used as a reference in the Emperor’s Imperial Castle6. It is interesting to see the Meiji government slowly adopting the Western influence as a means to exhibit national power. Moreover, the idea of having a Japanese architect learn the pedagogy of European architectural styles yet preserving the indigenous nature of Japanese heritage was critical in developing the new meaning for the bushido. Using what he learned from his mentor and combining it with his experienced travelling abroad, Tokuma had a unique approach to the design of the Imperial Castle. While the exterior carried traditional Japanese style (referencing the heritage of the Tokugawa era) the contrast of the interior was completely different in exhibiting lavish Western influence. The public spaces of the Castle were designed in a mixed style of neo-classical and baroque interventions seen in decorations and furnishings imported from the countries Tokuma visited for his research such as England, Germany, and most notably, France (figure 2). Here is how Tokuma aligned the creation of a new Japan identity with the values of the Meiji Restoration. The design of the castle’s interior reflected those of the most powerful and civilized nations. This was particularly clear in the design of the Throne Room (figure 3). Understanding that at its core, the Imperial Castle was Japanese in conception however the noble chamber of the Throne Room emphasized Japan’s new era of modernity through interventions from the West7. The ceiling had vast tessellations of historic paintings framed by curved cornices that descended to the walls panelled with flowering designs. What is interesting here is how the room has multiple layers to the ceiling, rather than the wall simply meeting the ceiling. Yet this simple act of multiple planes of highly ornamented features allowed Tokuma to communicate that the new era of Japan’s identity. The Throne itself was coloured in bright red and gold with silk canopies hanging on the sides with the Imperial coat of arms displayed forcefully. The lavish design of the public rooms such as ornamented furniture, exaggerated chandeliers and decorative flooring evoked ideas of Western influence that Japan was now adopting for the Meiji Era.

Traditional Japanese Architecture Adopting Western Styles

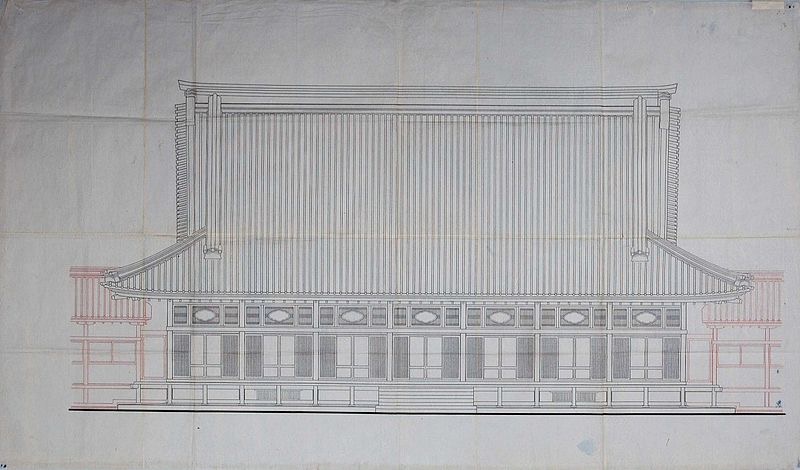

The relationship between the interior and exterior emphasized the narrative of the new monarchy evolving beyond its traditional past. While Tokuma embraced the heritage of traditional Japanese architecture, it is interesting to see elements of the baroque and neo-classical style present in the exterior of the Audience Hall (figure 4). Columns were evenly spaced similar to the arcades created by Corinthian pilasters as well as a central entrance flanked by evenly spaced windows. There was a unique dialogue between the interior and exterior that bridges the gap between European style and traditional Japanese architecture. In addition to the audience hall rooms such as the banquet halls, reading rooms, and administrative offices all displayed highly decorated interiors not for purely aesthetic reasons but because aesthetic choices were predicated on perceptions of relative national power8. What all these areas had in common was a ceremonial setting that set a standard for the new monarchy. By assimilating the lavish interiors with the idea of procession through the space, Tokuma designed a series of spaces that constantly reminded the observer of the power of the new Emperor.

7Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 76–80.

8Ibid, pp. 77.

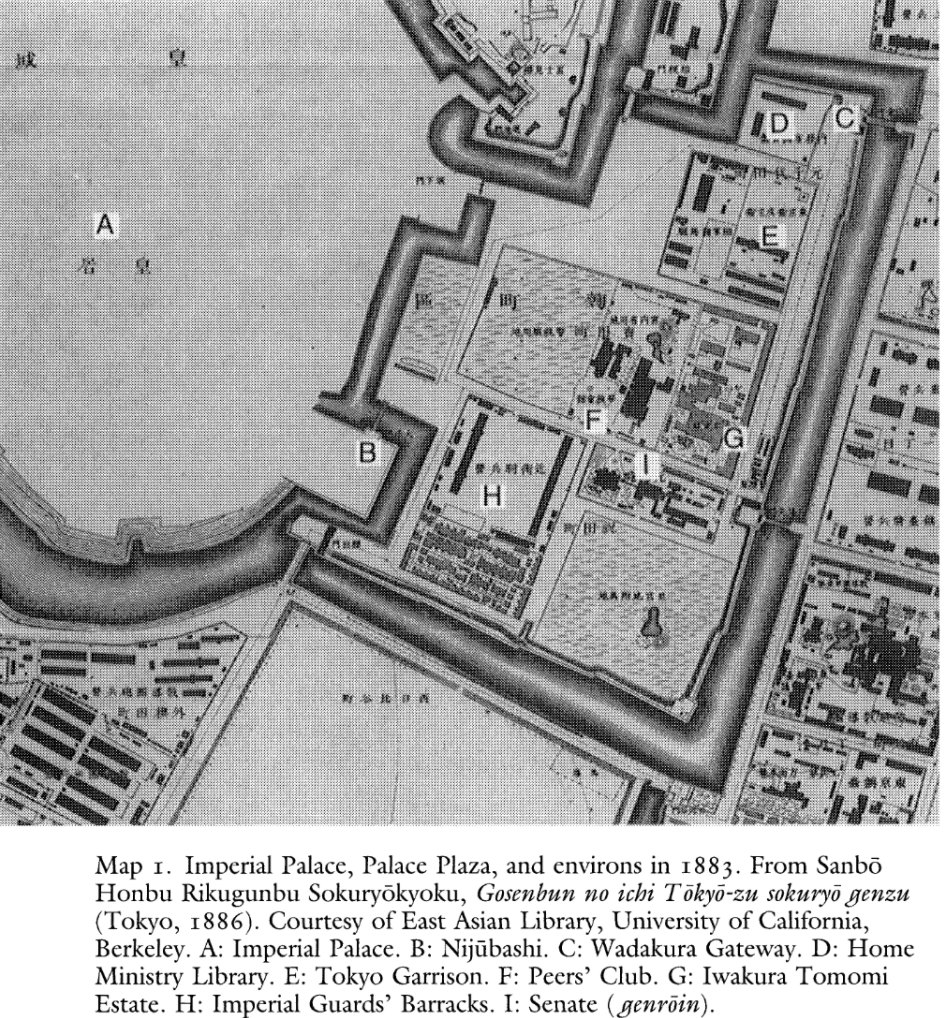

At the same time, the Office for Palace Construction took over the area in front of the main entrance to the castle to be used for the masses. During the Tokugawa Era, this space was used solely for high-ranking military officials and residences that did not engage with the public. A map of the area demonstrated the fragmented compartments over the area and did not respond to the castle’s surrounding context (figure 5). As a result, a new grandeur plaza was created such that the area would be a sublime stage for public rituals9. This cemented the values of the Imperial Castle to be a catalyst for the new era of Japan. The architectural language of national power extended beyond the castle interiors and into a new ceremonial public space that allowed the crowds to see and be seen by the Emperor. The plaza space allowed the values of the Emperor and the government to flourish among the lives of the Japanese people and thus redefining the idea of the bushido.

9Ibid, pp 78.

Conclusion

The design of the Imperial Castle, with a traditional Japanese exterior and innovative Western influence of the interior, created a new narrative of the bushido. While the traditional Tokugawa design of the Edo castle represented ideas of war, military defense, and dictatorship the unique design of the Imperial Castle exhibited ideas to those of the West of a united national identity. This empirical power represented the new era of Japan, one that remembers its heritage while striving towards a bright future. Furthermore, the plaza space directly fronting the main entrance to the Imperial Castle provided a location on which to diagram a new era for the nation. In the Meiji Restoration, the bushido was not the way of the warrior, but more importantly the way of a nation. However, this can be further interrogated as the basis of the Japan’s modernity through the rise of the Imperial government was predicated on the ideology of Western architectural influence. More specifically, the product of the colonial empire of Britain. While Katayama Tokuma was praised for his designs within the Imperial Castle, it must not be forgotten that his education was built upon the teachings of Josiah Conder, an architectural professor of the British Empire. Therefore, it is clearly evident within the Imperial Castle that although its interventions represent a new era of Japan, the building, the monarchy, and the redefining of the bushido ultimately follows the path of controversial ideologies of colonialism.

References

Oleg Benesch. Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 28, 2018, pp. 107–134.

Orui Noboru and Toba Masao, Castles in Japan, Tourist Library, (Tokyo, 1935), pp 72-73.

Oleg Benesch. Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 28, 2018, pp. 107–134.

Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 76–80.

Olive Checkland, Japan and Britain after 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015, pp. 73–82.

Images

Title Image: Birds Eye of the Imperial Castle completed October 1888. Tokyo Metropolitan Library. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tokyo_Imperial_Palace_pic_08.jpg

figure 1: Map of Edo, Japan in 1848. Public Domain

figure 2: Interior images of the Imperial Palace, 1889. Public Domain. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Tokyo_Imperial_Palace

figure 3: Illustration of the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55232

figure 4: Audience Hall elevation drawing. Tokyo Metropolitan Library. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tokyo_Imperial_Palace_pic_09.jpg

figure 5: Map of the Imperial Palace plaza space. Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 80.