The Indian Residential School (IRS) system operated in British Columbia from 1861 to 1984.1 Over a hundred years, these institutions operated to systematically carry out the cultural, and often, corporeal annihilation of Indigenous people across Canada.2 Of focus in this essay is the inextricable link between the colonizing mission of the Government, and the architectural style of Residential Schools as the vessel for the dissolution of First Nations culture. Through an exploration of space and form, it becomes apparent that the Colonial and Religious executors of the IRS system relied on these architectural moves to exacerbate the isolation, fear, and emotional abuse experienced by ‘students’ of the system. A recurrent theme that reveals itself in exploring this brutal colonial practice are the complicated relationships sustained by the architecture of these spaces that all served to the end of “sociocultural dissolution”: that of christianity, control, and physiological repression.3 Looking at the St. Eugene Indian Residential School as an example of this, I look at two specific architectural instances of decreasing scale-the facade and the dormitory-as idiosyncratic to the Government’s colonial exertion of cultural annihilation amongst First Nations groups in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Before looking specifically at St. Eugene, it is imperative to understand the context of what conditions led to the need of these architectural instruments of cultural genocide. The IRS system came about after previous unsuccessful attempts of having children from First Nations reserve voluntarily attend day schools, as “absenteeism proved problematic, [since] children traveled with parents on seasonal hunting trips and for ceremonies”.4 The Government opted then to pursue a model that sought to more forcefully ‘integrate’ to a white, catholic, anglicized society, to be achieved through Residential ‘boarding’ schools staffed by members of the Roman Catholic Church (amongst others).5 This evidences how the primary motivation behind the IRS lay in exerting assimilationist policy to “break Aboriginal children’s links with their communities and cultures [as] a means to absorb them into a dominant society”, with ecumenical rhetoric serving as an excuse of this end.6

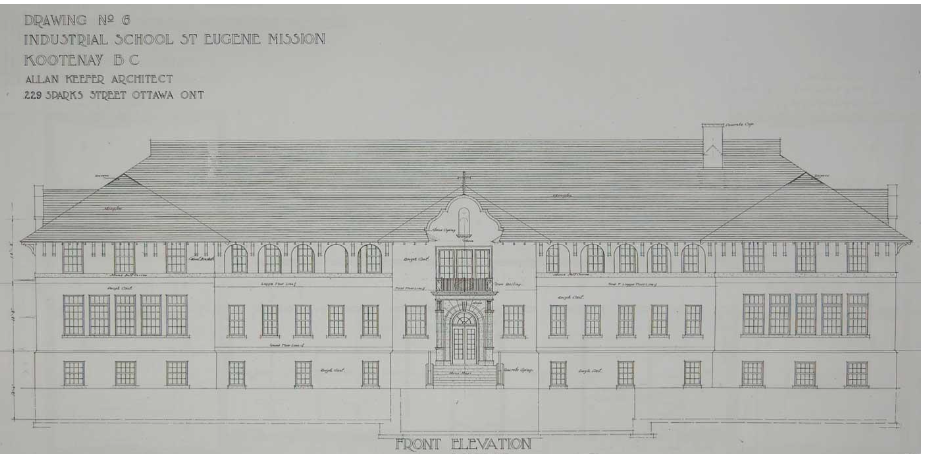

The first example of how this was done architecturally was through the exterior of these schools when children first arrived, where the looming, imposing facade immediately signalled an overbearing sense of authority.7 Constructed in Cranbrook in 1912, the St. Eugene Indian Residential School operated until its closure in 1980; it located on the territory of the Kutnaxa first nation, and was run by the Roman Catholic Church. Referring to Fig. 1 showing the facade of said school at Cranbrook, this technical architectural drawing clearly depicts the strictly symmetrical appearance of the school, with a central stairway leading to an entrance “capped by a spire, highlighting the religious curriculum taught within”, as was common with most Residential Schools.8 Comprised of three stories, the ends of the school are also capped with some type of shingling that sits atop neatly distributed windows. The lack of any finer detail, including the materiality of the building’s exterior on the drawing further communicates an overwhelming sense of functionality that these drawings, and spaces, would serve. Thus, it is the strict symmetry and imposing scale communicated by this drawing that reveals the underlying architectural moves to communicate a sense of authority and cultural-religious superiority over incoming students. The result, recounted through the stories of survivors, was a first impression upon arrival of disorientation, fear, and alienation that all accentuated the verbal, emotional, and physical abuse exerted by the colonizers.9 Therefore, it is this language of control and dominance that enabled the Government to carry out its assimilationist agenda through architectural means by pursuing a visual architectural language of fear, of the imposition of power, and of the superiority of Catholic institution evidenced in this drawing.

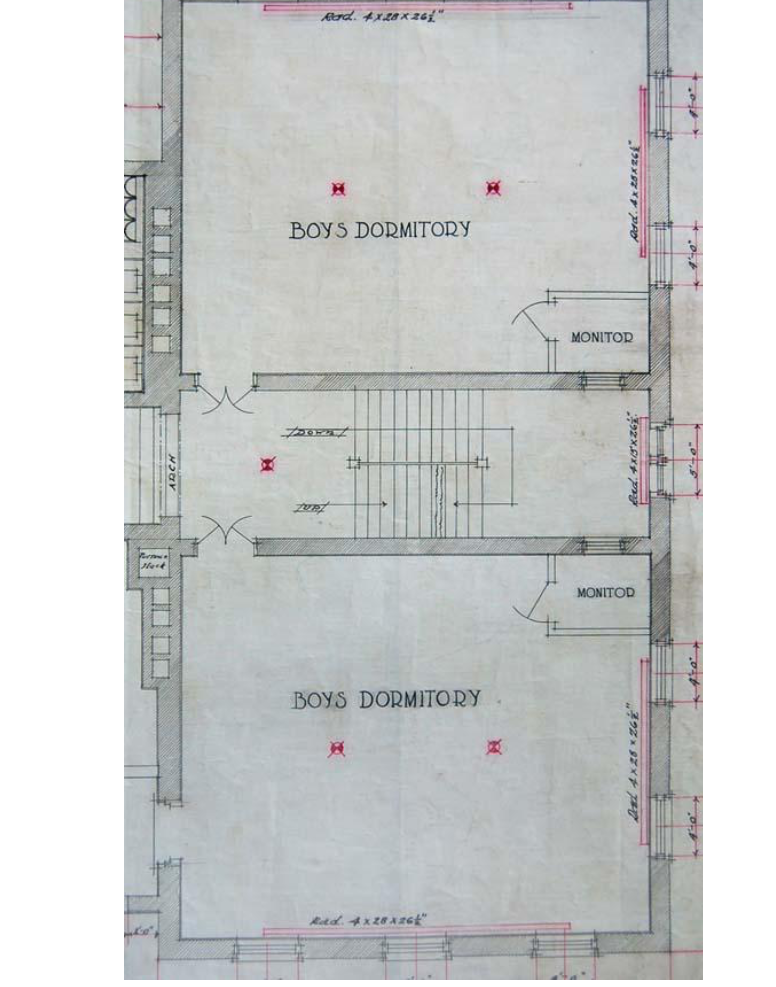

Past the facade, the interior of the Residential school was to an even greater extent complicit in exposing Indigenous children to endemic isolation, supervision, and corporeal abuse.10 The reason for this is lies in how the layout of Residential schools were fundamentally oppressive as they “produced compartmentalized spaces alien to children from Indigenous cultures” through a rectilinear layout of secluded spaces.11 This fact was exploited by colonial architects, and is most noticeable in the space of the Dormitory. On the one hand, Dormitories presented a uniquely harmful space because of its aforementioned alienness to the shared familial sleeping arrangements prevalent in First Nation’s cultures. This is demonstrated in Fig.2, a plan drawing of a section of St. Eugene’s, where two large open spaces labelled ‘Boy Dormitory’ lay intersected by a long rectilinear hallway. Of note are the lack of any human figures, or furniture, which graphically evidence the lack of importance given to the human occupants of these spaces, eventually was manifested by overcrowding and sickness of students.12 But more importantly is the space itself, as the drawing demonstrates the dimensions of the windows (around 4 feet) and the large footprint of the room that all serve as an indication of this compartmentalized yet highly vacuous room that had the effect of further disorienting children due to a feeling of vulnerability, and loneliness. As told in one experience:

“When I first got introduced to the dorms … I had never slept away from the proximity and closeness of a loving family. And suddenly there were thirty or forty little beds lined up side-by-side … in my first year it was very frightening to be in a big, huge dorm with all these other little kids […] the whole culture of the dorm was one of confinement”.13

This first hand account further supports the idea that the form and layout of the building exacerbated and instigated a sense of fear amongst sequestered children through the spaces they inhabited. It is for this reason that there is a clear link between the architectural form of St. Eugene—and residential schools at large—as an active agent in pursuing an assimilationist policy against Indigenous communities.

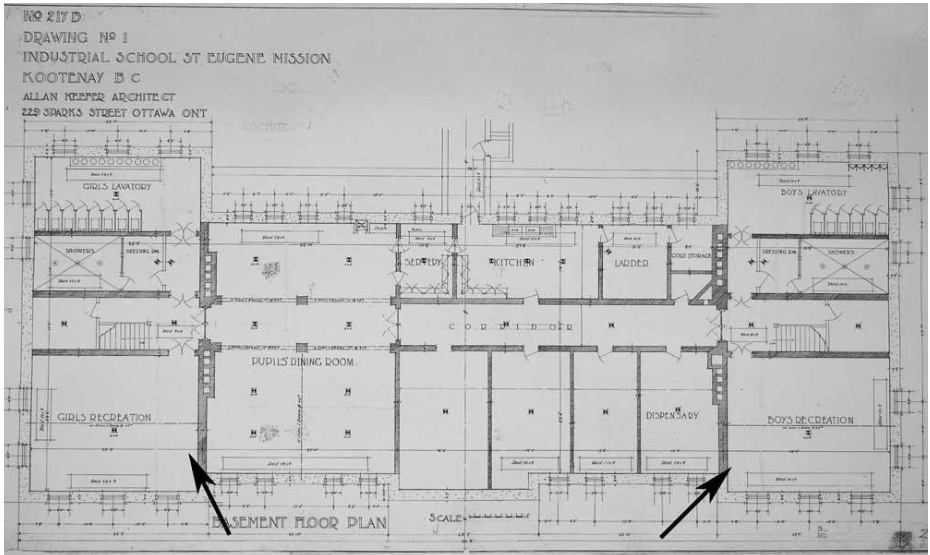

Additionally, dormitories and lavatories at IRS were designed around the aim of full surveillance, a means to also control, abuse, and intimidate Indigenous children. Much like the accounts of the vacuousness of large dorm rooms acting to increase the isolation of students, many also included an added ‘Monitor Room’.14 Again, this is seen clearly in Fig. 2, where amongst what would arguably be a large open space of rows of beds, would be a walled room contains a Monitor. This space would thus serve as a spatial reminder and apparatus for children to feel isolated, yet observed, and for the monitors to feel emboldened in having constant oversight of ‘students’; particular to this drawing, there is a window on the wall looking out into the stairway, evidence of just how significant this need to control was in the operation of this school. As mentioned by Carr, this method carried strong ties to the notion of a Panopticon, and by extension, incarceration and was certainly then exploited by Monitors and staff to ensure “the students were always within the monitoring and colonial gaze of school staffs”.15 This, however, extended into the bathrooms, where the lack of division between showers and the supervision of the Monitor boiled down to the succinctly violative act of surveying children bathed in a confined space. This is clearly depicted in Fig. 3, a similarly instructional construction plan of the layout of one floor of St. Eugene’s. It demonstrates the intensely symmetric overall layout, spatially delineating the gender-based division that existed alongside that of age. Moe importantly, the drawing also shows the respective “Showers” room as being at the ends of the building, with no divisions, and secluded behind many layers of compartmentalization. Taking these spatial qualities with the fact that Monitors oversaw the bathing of children in a room that is separated, walled, and behind closed doors further provides evidence of how an intentionally isolationist design enabled colonial abuses that sought the dissolution of Indigenous culture through the emotional and physical abuse of the Indigenous body.

It is clear now that the architecture of St. Eugene Indian Residential School, and the IRS system at large, was such a powerful agent in the cultural dissolution of Indigenous communities because of its disruption of Indigenous children’s sense of place, sense of space, and its enabling of constant surveillance. Using the example of the facade, and the interior dormitories (and by extension, lavatories) these two specific instances—and the three figures herein referenced—imposed an emotional sense of confusion, fear, and control. The former, utilized an oversized, imposing exterior rife with symmetrical and ecumenical symbolism immediately instilled in children a sense of fear, disorientation, of Colonial cultural superiority. Additionally, large vacuous dormitories, and open shower spaces, created a duality between a sense of vulnerability through isolation, and one of overwhelming surveillance; this thus acted as a backdrop by which other colonial exertions of power could unfold, often hidden from view. It is also worth mentioning the limitations of this exploration, as it does not delve into the incredibly complex and brutal narratives of pedophilia experienced in these institutions, as well as those of sickness, physical beatings, death and generational trauma that remain to this day key in understanding this period of Canadian history. Nonetheless, within an architectural lens, it is now clear that the colonial Government explicitly used the architectural style of these schools as the “material articulations both of colonialism’s assimilationist violence and its agenda of eliminating Indigenousness from the BC landscape”.16

Footnotes:

1. DE LEEUW, SARAH. 09/01/2007. “Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools.” The Canadian Geographer 51 (3): 339-359. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.2007.00183.x. p. 343.

2. Ibid.

3. Carr, Geoffrey Paul. 2011. “’House of No Spirit’ : An Architectural History of the Indian Residential School in British Columbia.” Electronic Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 2008+. T, University of British Columbia. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0071770. p. 90.

4. Carr, Geoffrey. 01/01/2009. “Educating Memory: Regarding the Remnants of the Indian Residential School.” Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada 34 (2): 87-99. P. 89.

5. Ibid.

6. DE LEEUW, SARAH. 09/01/2007. “Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools.” P. 343.

7. Ibid, 344.

8. Carr, Geoffrey. 01/01/2009. “Educating Memory: Regarding the Remnants of the Indian Residential School.” P. 92.

9. DE LEEUW, SARAH. 09/01/2007. “Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools.” P. 343.

10. Carr, Geoffrey Paul. 2011. “’House of No Spirit’ : An Architectural History of the Indian Residential School in British Columbia.” p. 92.

11. Ibid, 82.

12. DE LEEUW, SARAH. 09/01/2007. “Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools.” P. 351.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid, 343.

15. Carr, Geoffrey. 01/01/2009. “Educating Memory: Regarding the Remnants of the Indian Residential School.” P. 95/ DE LEEUW, SARAH. 09/01/2007. “Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools.” P. 345.

16. Ibid.

Bibliography:

Carr, Geoffrey. 01/01/2009. “Educating Memory: Regarding the Remnants of the Indian Residential School.” Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada 34 (2): 87-99.

Carr, Geoffrey Paul. 2011. “’House of No Spirit’ : An Architectural History of the Indian Residential School in British Columbia.” Electronic Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 2008+. T, University of British Columbia. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0071770.

DE LEEUW, SARAH. 09/01/2007. “Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools.” The Canadian Geographer 51 (3): 339-359. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.2007.00183.x