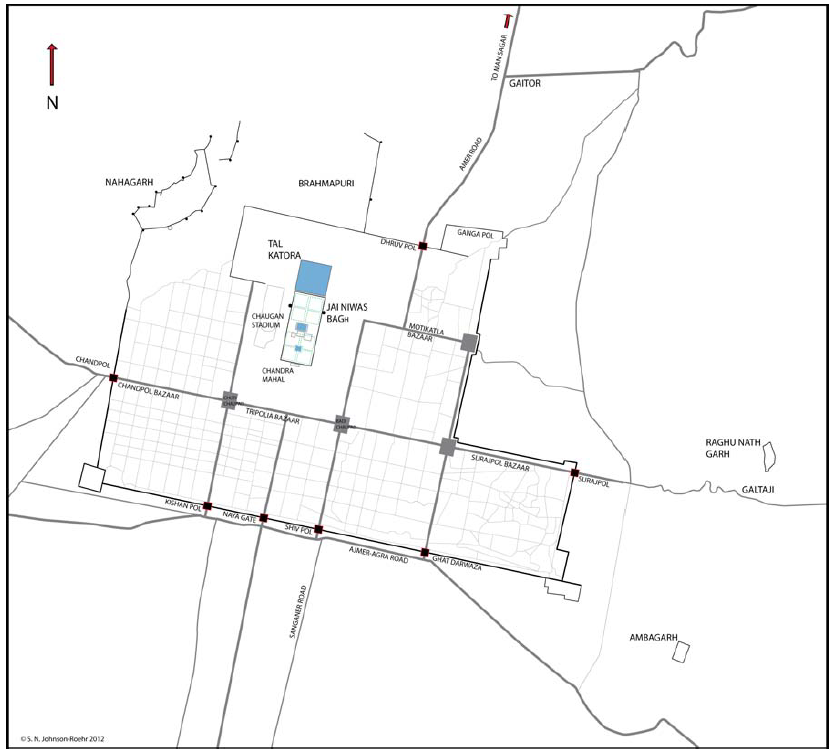

Jaipur, the capital of India’s Rajasthan state, is notably one of the first planned cities in India’s history. Inaugurated in 1727, the new city was a mathematically organized urban landscape that promoted growth for the Kingdom of Amer and encouraged cultural diversity. The Kingdom of Amer, led by Sawai Jai Singh, was originally located in Amber. This city had a fortified palace that had protected the royal family for a long time, however, as trade was increasing and there was much potential for growth in the city, Sawai Jai Singh felt a relocation to accommodate expansion was necessary1. The construction process involved definition of blocks and boulevards. Streets were wide to accommodate processions for events with shops lined up along them. And while Jaipur was also designed as a fortified city, the Prince paid special attention to a permeability within the city walls by incorporating multiple gates. These gates connected the town to existing major trading roads to establish Jaipur as a critical location along the route2 as well as defined major corridors within the city (see Figure 1). Further to the trading route, the location of Jaipur was also positioned close to a popular pilgrimage route with multiple villages scattered nearby, serving as an opportunity for labour and consumers for exports from the new city.

Historically, the organization and planning of Jaipur has often been thought of as influenced by a nine-square mandala3, specifically out of the assumption that Jaipur was constructed out of a Hindu-focus design. However, Jaipur is known as a city that includes multiple religious groups that live and work together respectfully. When analyzing the influences present in the design strategy of this new city, it is important to consider what narrative has led to the assumptions to date, how the influence of multiple religions, as opposed to a singular one, impacted the design of the city, and what other possible sources of influences could have been.

In the traditional narrative of the history of Jaipur, scholars and historians discuss in great detail the influence that a Hindu-Vedic approach has had on the layout of this city, largely attributing this to the fact that the Prince, Sawai Jai Singh, was of the Hindu religion. However, this also requires the assumption that the city planning and design focuses on one particular religious view that guided its conception. It is important to consider why the history of Jaipur has been so focused around this particular perception. The narrative surrounding architectural history is largely driven by European interest. When there was growing interest in Europe of “discovering” South Asia’s architectural history, the Europeans developed a classification system with which to discuss and organize their findings4. In particular to this system, categorization of these works was heavily dominated by classification of the relevant, or perceived, religion. The European interest of South Asian art and architecture led to the founding of the Asiatic Society in 17845. Since then, textbooks used in architecture schools have trained students in the thinking of this classification system. As new textbooks were produced, they relied heavily on the work of the textbook previously, deeply instilling this classification system that focused intensely on race and religion being primary drivers of art and architectural development6. The use of this classification system has thus hindered a critical analysis of the planning of Jaipur as a city outside of the bounds of Hindu influences. It discredits the importance of harmony behind multiple cultures and religions that was made possible in the construction of Jaipur and does not consider how key landmarks could have held more significant importance to the location and setting of the city.

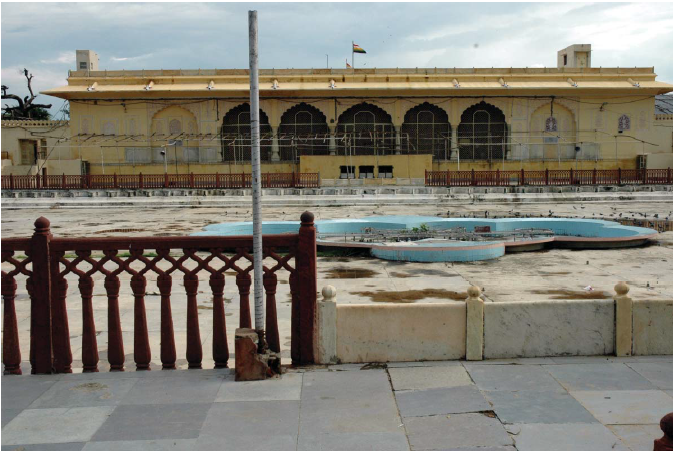

Ganga-Jamni tehzib, as defined by Yamini Narayanan, “symbolizes a union of two vital and diverse religio-cultural strands that are far mightier together than each would be separately.”7 In other words, the acceptance, acknowledgement and recognition of multiple religions played a crucial role in the design of this new city. Further, as spoken by a local in our current time period, “We are nothing in Jaipur without it, this is how the city was born, and how will it then live without it?”8 As mentioned, cultural diversity had a role to play in the very conception of the city of Jaipur. Sawai Jai Singh made obvious efforts to cultivate cross-pollination. For example, members and advisors of his court came from various religions, ensuring that there was a diverse range of intellectual thought and concern, with none dominating9. Further, the discrete presence of temples and mosques do not alienate any particular religious group in the city and the wide streets are designed to accommodate many types of processions10. The main streets were prioritized to showcase shops that promoted the city’s economies, with mosques respecting this design mandate by being constructed within inner lanes so as not to disrupt the cohesive look of the city11. Despite the bold forms that were found in the original capital, Amber, temples were also inconspicuous (see Figure 2). Sawai Jai Singh’s respect and allowance of various religious practices to exist in one city encouraged a dynamic city that could thrive both culturally and economically12.

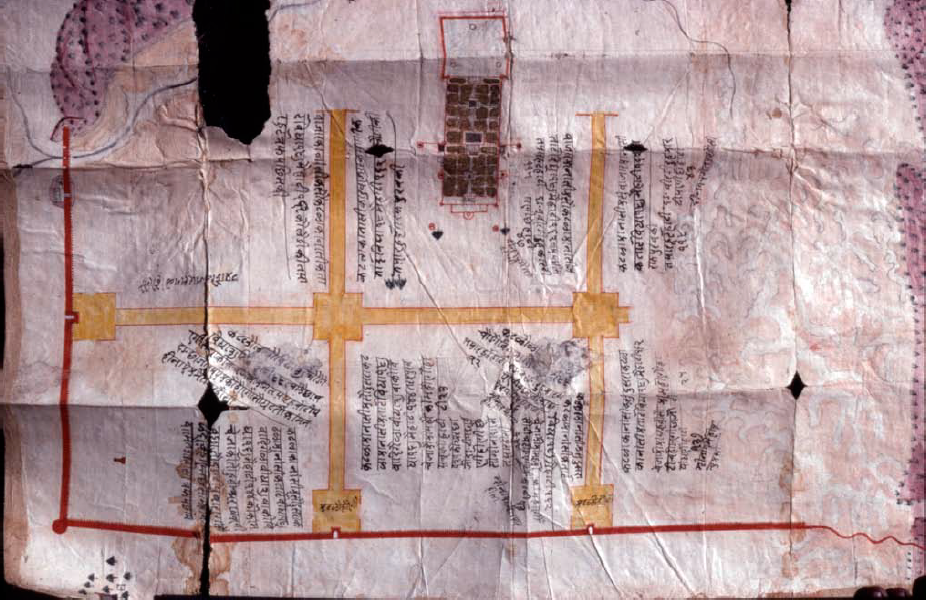

It is somewhat logical to consider the main influence for the organization of the city of Jaipur originated from Vedic reasoning, as the Prince was educated in the formal study of Sanskrit texts13. However, in all the documentation found of the planning of the city, there is no mention of reference to Hinduism and any symbolic or literal references14. According to Susan N. Johnson-Roehr, most of these assumptions have been based on the series of plans created to document the development and construction of Jaipur. These maps have taken on an understanding that they are progressive documents, with more detailed plans referring to a further developed construction stage15. Johnson-Roehr debates this and questions what the different lines and symbols used could mean alternatively if not supporting a Vedic-focused city design. In support of this argument, Johnson-Roehr proposes that the map designated by scholars as a first stage planning document, determined to be showing an arrangement of walls and streets, could actually be viewed as a canal construction document16 (see Figure 3).

Throughout the various maps available of the city, there are two key elements that are repeated. These elements, the Jai Niwas Bagh, which was a pleasure garden located in the centre of the city, and the Tal Katora tank, which was the water source to the garden, display an importance of the place that was being designed (see Figure 3, 4). Jai Niwas Bagh was constructed by Sawai Jai Singh in 1713 in the manner of Mughal chārbāgh. This quadrilateral garden style features cross-axial canals and a centralized pavilion and originated from Persian garden design17. Amer held many of these garden designs, such as the Aram, Mohan Bari and Dilaram Baghs, making it clear that Sawai Jai Singh was familiar with developing the ideologies of different architectural styles throughout his kingdom in various forms and sizes18 (see Figure 5).

When looking at the planning of Jaipur, it is clear to see how the relationship the city had with Jai Niwas Bagh and its location was key in the strategy for development. As the city was planned mathematically, the relationship between this space and the larger network of bazaars and streets are visibly proportional19. While this module of chārbāgh could be interpreted as not too different from the proportions of mandala in pattern, the philosophy that the city follows chārbāgh seems more in line with how the city identified itself then and today.

European analysis of indian art and architecture has aided in an often one-sided discussion about the foundation and formation of work in South Asia, including the discourse around the formation of Jaipur as a planned city. This likely stemmed from a long-distilled history of how to approach non-European artwork, that still has impacts today on how South Asian work is discussed. However, by recognizing these barriers in our understanding of architecture, there is opportunity to reexamine the influences present and gain a deeper understanding of what made cities like Jaipur so influential and critical in our global history.

Notes

1Susan N. Johnson-Roehr, “Centering the Chārbāgh.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians, 2013), pp. 28-47, 32.

2Johnson-Roehr, 32.

3Francis D. K. Ching, Mark M. Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash, “South Asia: Jaipur and the End of the Mughal Empire,” A Global History of Architecture (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2017), pp. 611-612, 612.

4Jyoti Hosagrahar, “South Asia; Looking Back, Moving Ahead-History and Modernization,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians, 2002), pp. 355-369, 356.

5Hosagrahar, 356.

6Hosagrahar, 358.

7Yamini Narayanan, “Hinduism and Space: Place and Identity in Old Jaipur.” Religion, Heritage and the Sustainable City: Hinduism and Urbanisation in Jaipur, (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), pp. 125-158, 129.

8Narayanan, 129.

9Johnson-Roehr, 31.

10Catherine B. Asher, “Jaipur: City of Tolerance and Progress,” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (South Asian Studies Association of Australia, 2014), pp. 410-430, 418.

11Asher, 421.

12Asher, 420.

13Johnson-Roehr, 33.

14Johnson-Roehr, 33.

15Johnson-Roehr, 33.

16Johnson-Roehr, 34.

17Johnson-Roehr, 38.

18Johnson-Roehr, 38.

19Johnson-Roehr, 42.

Bibliography

Asher, Catherine B. “Jaipur: City of Tolerance and Progress.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, South Asian Studies Association of Australia, vol. 37, no. 3, 2014, pp. 410–430., doi:10.1080/00856401.2014.929203.

Ching, Francis D. K., Jarzombek, Mark M., and Prakash, Vikramaditya. “South Asia: Jaipur and the End of the Mughal Empire.” A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2017, pp. 611-612.

Hosagrahar, Jyoti. “South Asia: Looking Back, Moving Ahead-History and Modernization.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 61, no. 3, 2002, pp. 355–369., doi:10.2307/991789.

Johnson-Roehr, Susan N. “Centering the Chārbāgh.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 72, no. 1, 2013, pp. 28–47., doi:10.1525/jsah.2013.72.1.28.

Narayanan, Yamini. “Hinduism and Space: Place and Identity in Old Jaipur.” Religion, Heritage and the Sustainable City: Hinduism and Urbanisation in Jaipur, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017, pp. 125–158.

Images

Asher, Catherine B. “Jaipur: City of Tolerance and Progress.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, South Asian Studies Association of Australia, vol. 37, no. 3, 2014, pp. 410–430., doi:10.1080/00856401.2014.929203.

Johnson-Roehr, Susan N. “Centering the Chārbāgh.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 72, no. 1, 2013, pp. 28–47., doi:10.1525/jsah.2013.72.1.28.