Displacements and Dispossessions resulting from The Public Lands Act of 1853

The road systems constructed in Ontario as a result of The Public Lands Act of 1853 have historically played a significant role in the processes of displacement and dispossession of indigenous communities from their traditional territories and homes, reinforcing the mechanisms of settler colonialism through infrastructural efficiency and European modes and techniques of land re-organisation and construction. These road networks in many cases became the basis of today’s modern road system, preserving and perpetuating these historic systems of destruction, control, and exploitation.

The construction of solid roadways is anything but new. Humans have been manufacturing roads from as far back as 4000 BCE in ancient Mesopotamian – using mud bricks held together by naturally occurring bitumens. [1]

The Roman Empire, often pointed to as the nucleus of European modes of thinking and organisation today, were historically significant road builders. From as early as 312 BC, the Roman Empire (in support of its military campaigns) built strong stone roads throughout Europe and North Africa. At its peak, the Roman Empire was connected by 29 major paved roads branching out from Rome and covering 78,000 kilometers.[2]

In the Canadian context, historically the river systems of Ontario were its first transport networks: networks which were used by the indigenous communities of the area and which where initially adapted as critical transportation routes by the European settlers upon their arrival in the Americas. [3] However, as Europeans began colonizing the Americas, they carried with them across the ocean the habits and legacies of road building from their homes.

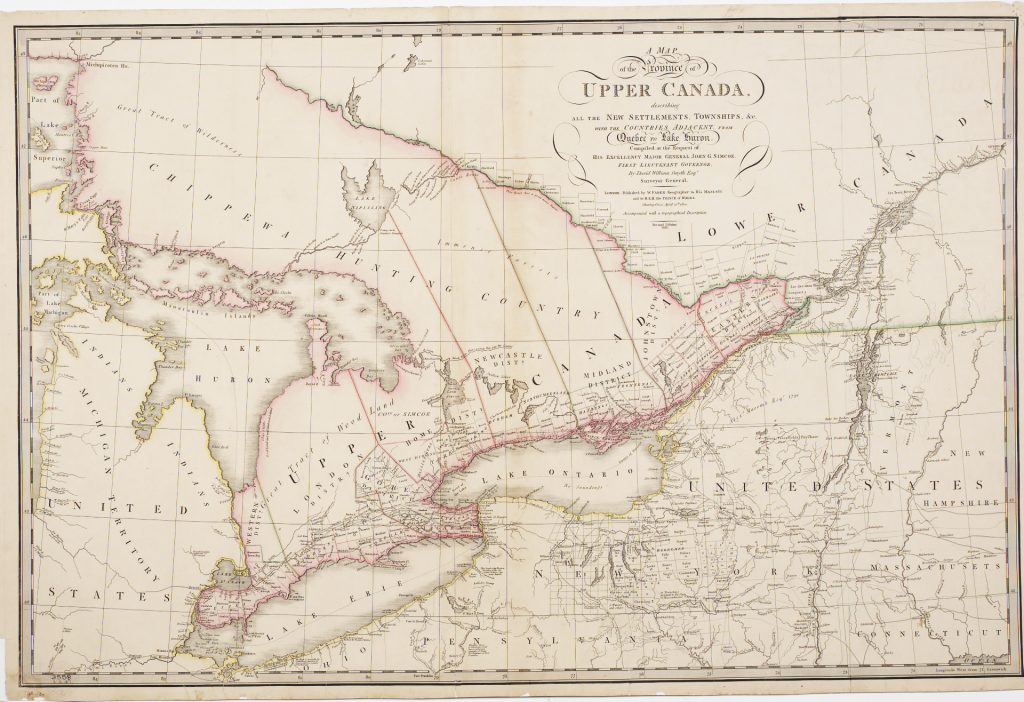

In Figure 1, the first printed map of Upper Canada from 1818, you can see that most of what is now Northern Ontario is left blank, labeled only as a “Great Tract of Wilderness” and “Immense Forests” and identified broadly as “Chippewa Hunting Country.” It is also clear from the map that most of the settler activity at this time was located along the major water routes – such as the shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie and along the Ottawa River, where land is beginning to be surveyed, grided, and sold to Europeans. As the colonisation of this area continued and the populations of settlers increased, the colonial ambitions of the settler government turned to these previously less documented landscapes. As with all of Canada however, these areas were already home to multiple Indigenous communities and nations, including the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee, the Cree, and others.

In 1853, The Government of Canada passed The Public Lands Act as a mechanism to increase settlement and colonisation in these northern areas of what is now Ontario. As described in Information for Immigrants, Settlers and Purchases of Public Lands, published in 1862, the Act gave legal authority for land to be given to European settlers upon the conditions that they build a house and clear the land for farming:

“Government has opened several great lines of road on which free grants of one hundred acres are given to actual settlers. The conditions of location are:—That the settler be eighteen years of age. That he take possession of the land allotted to him within six months. That he build a log house 16 by 20 feet. That he reside on the lot and clear and cultivate 10 acres of land in the course of four years. Members of a family having land allotted to them may reside on a single lot, thereby exempting them from building and residence on each location.” [4]

The government in turn promised to provide access to this land as a means of incentivising the settlements and to increase its efficiency – a promise which become physically manifested in the construction of the colonization roads. The government went on to build over 1,600 kilometres of road networks over the following 20 years to provide access to these grants as a direct result of the legal mechanisms of the Public Lands Act.[5]

The rights of the Indigenous communities who had previously occupied these lands were articulated quite differently from those of the settler population. They were officially excluded from the resettlement project. Although there is currently a treaty in negotiation covering much of the land area of the historical Ottawa-Huron region, during the resettlement process when free land grants were given to European settlers, local Indigenous communities petitioned the state for their own lands and were rejected. Reserves where created and these communities were relocated to make way for these new settler communities.[6]

This colonial settlement process was also driven by the economic consumption of Europe via Canadian extracted lumber and produce.[7] The majority of the lumber milled in the area was transported back to Europe for construction, positioning these forests of northern Ontario as reciprocal landscapes to the structure in Britain and France being built with this Canadian lumber. [8] This material and economic entanglement provides additional context for the expansion of the colonial footholds in Ontario during this period.

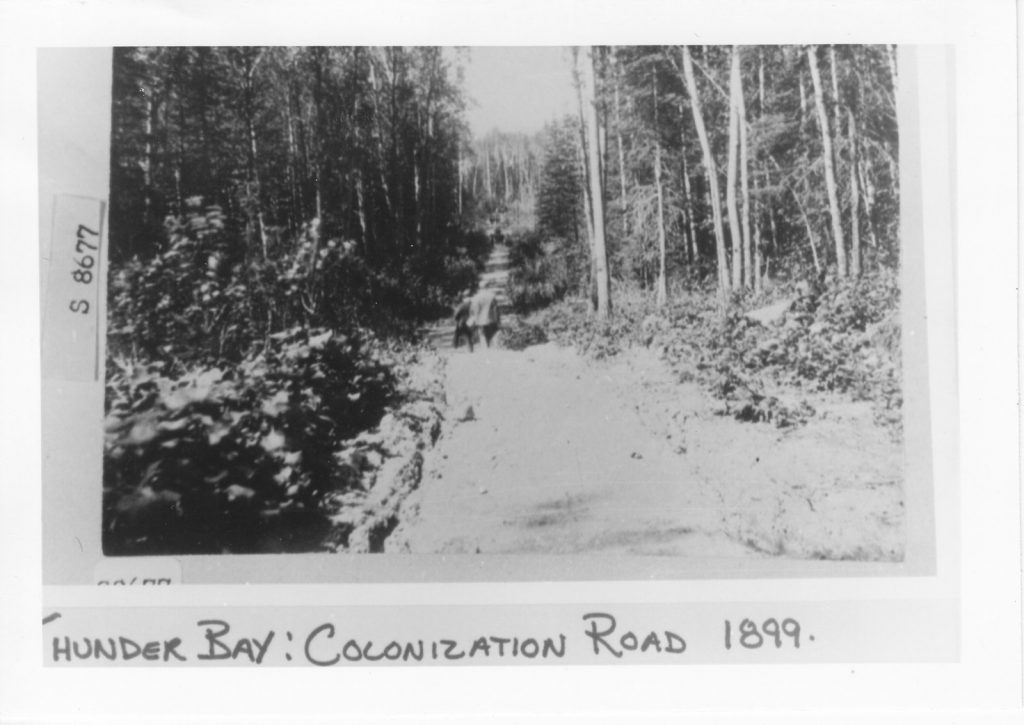

The construction of these road networks was also physically violent and destructive in their own processes of creation. The roads required large areas of forests to be cleared and existing ecological communities to be severed by these pathways. These physical scars resulting from these 1,600 kilometers of road can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, historic images of early colonisation roads in Ontario. Figure 2 shows the division of a forest by the creation of a colonization road near Thunder Bay, and Figure 3 shows a similar division of an ecosystem during the construction of the colonisation road between Fort Frances and Emo.

While most of these early roads were simple dirt tracks, early methods of road improvement included the “corduroy” roads: rows of cut logs. These roads where notoriously uncomfortable for both horses and riders, and destructive for wheels. Later, more effective plank roads were introduced. They became the preferred technology by the 1850s when split and sawn timber became readily available from local mills. However, these plank roads often only survived a couple seasons without proper maintenance. Later in the century macadam roads would become the preferred technology. [9]

Macadam roads, invented in England by John Loudon McAdam, a road builder who began running a horse drawn roller over a gravel layer to compact it, are considered the origin of modern asphalt roadbuilding techniques. Other road builders later began to add hot asphalt to the gravel to keep down dust and hold together the stone, a process called “tarmacadam” after its inventor.[10]

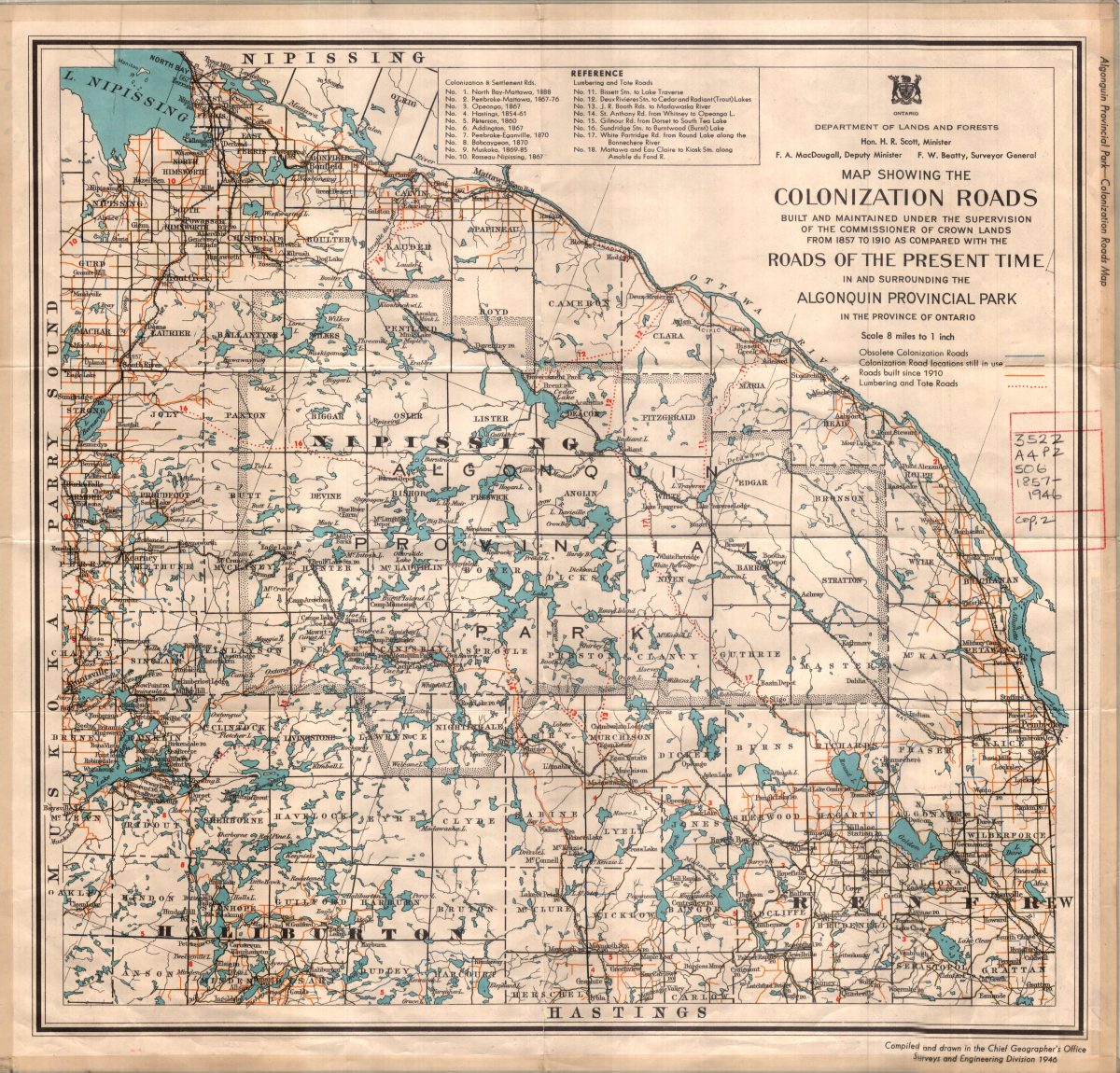

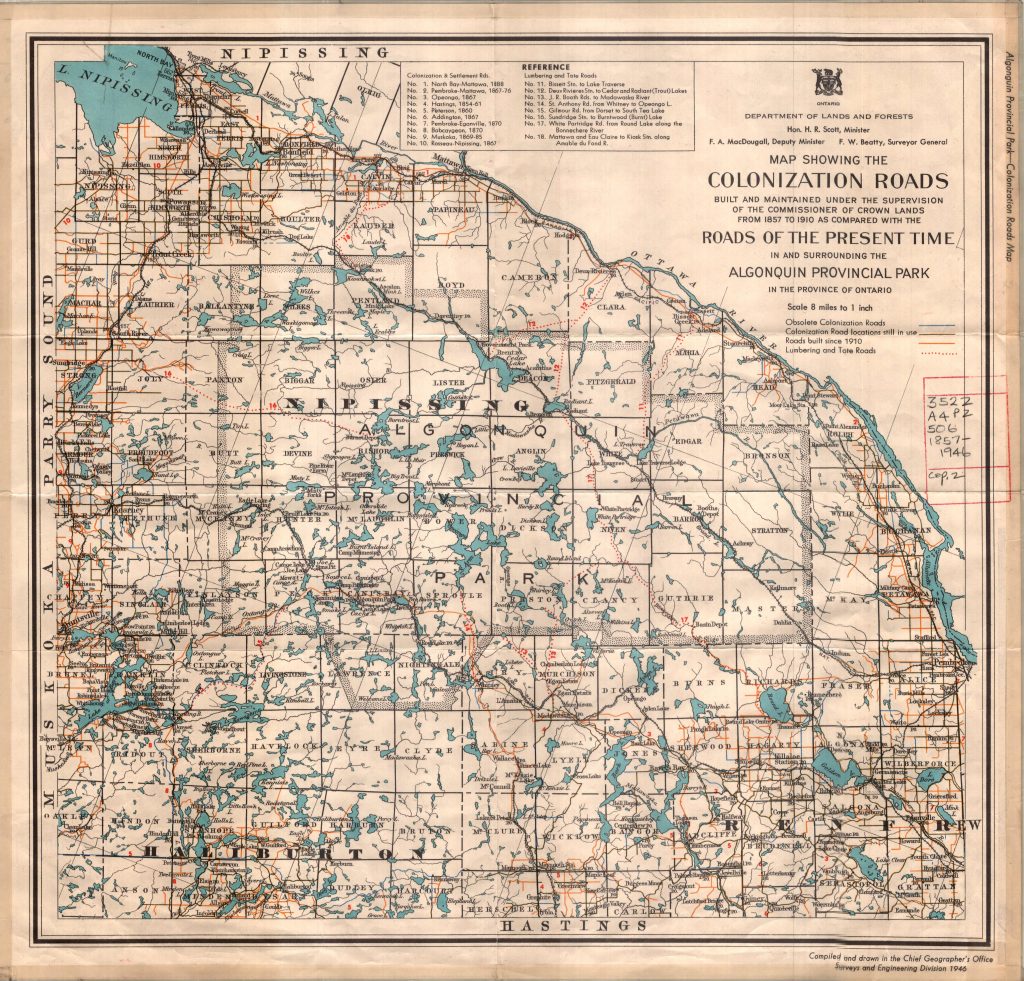

Figure 4 shows the extent of the colonization roads built and maintained under the supervision of the commissioner of Crown Lands from 1857 to 1910 in the Nipissing and Algonquin Provincial Park areas of Ontario. It is worth noting some critical inclusions and exclusions related to these maps. Waterways are the only element of the existing landscapes which are included (as they form the historic backbone of the transportation infrastructure). Otherwise, information about topography, vegetation, existing ecosystems and communities are all left out. This allowed for easy subdivision of the land into grided parcels along the East/West and North/South axis of the map – ideal to transfer the land to new settlers for forestry and agricultural production. The increasing presence of the settler merchants, lumbermen, and farmers in these areas brought about the shift to new forms of social organization based on permanent, as opposed to seasonal, habitation and on roads and railways, as opposed to lakes and rivers, as primary modes of transportation.[11] These shifts are manifested and embodied in the maps produced at the time, which can be viewed as both artifacts of this colonisation and enabling tools of its processes.

In this way, the process of colonisation in Ontario was as much founded and enabled by a production and accumulation of knowledge about the landscapes as it was by the physical infrastructure of the roads. The understanding of these ecosystems and communities as potential agricultural production networks and the various surveys and maps created to document these spaces gave the state the confidence to open the areas of Upper Canada for settlement by laying out townships and building these networks of colonization roads. These events all played pivotal roles in the shift toward the accelerated exploitation of natural resources and the expansion of a settler population in the region.[12] By connecting these new settler communities via these new infrastructural systems which spanned huge distances, the time and space between them were compressed and the power geometries of the areas were remade, all in an effort to increase the efficiency of these new landscapes of production.[13]

Many of these early colonization roads are still in use today and have in fact been expanded. Many of these roads have become a part of the modern provincial highway network and even the Trans-Canada highway.[14]

For Indigenous communities living in Canada today, multinational forces colonizing Indigenous lives and territories remain foreign empires, regardless of whether the power that is exerted comes from a single state source (such as the Canadian government during its creation of the Colonization road networks in the 1800s) or combined state, corporate, and multinational sources (as are more common today in the context of globalisation and multinational corporate power structures).[15] These colonisation roads which have survived thus can be seen as a historic and lasting severance of these peoples and communities from there traditional homes and ways of life. These roads continue to reinforce these mechanisms of settler colonialism through infrastructural efficiency and reproduction of European modes and techniques of land re-organisation and construction, the same ideals as those of the colonial power structures they were founded upon and built to support.

Endnotes

[1] Rickie Longfellow, “Back in Time: Building Roads,” Highway History, Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot. gov/infrastructure/back0506.cfm5

[2] C. A. O’Flaherty, Andrew Boyle, Highways, Fourth Edition. Elsevier, 2002.

[3] Murray, Derek. Equitable Claims and Future Considerations: Road Building and Colonization in Early Ontario, 1850–1890, Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, Volume 24, Number 2, 2013, https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/jcha/2013-v24-n2-jcha01408/1025077ar.pdf, 162.

[4] WM. M’Dougall, Information for Immigrants, Settlers and Purchases of Public Lands, With Maps, Showing The Newly Surveyed Townships, Colonization Roads, &c, of Canada. Hunter, Rose & Lemieux, 1862, 9.

[5] Sharon Bagnato, and John Shragge. Footpaths to freeways: the story of Ontario’s roads: Ontario’s bicentennial 1784-1984. Downsview, Ont: Ontario Ministry of Transportation and Communications, 1984, 17–19.

[6] Murray, Equitable Claims and Future Considerations, 166.

[7] Graeme Wynn. Timber Trade History, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2013. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/timber-trade-history

[8] Jane Hutton. Reciprocal Landscapes, Stories of Material Movements. Routledge, 2019, 16-17.

[9] The Ministry of Transportation 1916-2016: A history, Ontario Ministry of Transportation, accessed 15/02/2021, http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/about/mto-100/index.shtml

[10] Vince Beiser. The world in a grain : the story of sand and how it transformed civilization. Riverhead Books, 2018, 52-53.

[11] Murray, Equitable Claims and Future Considerations, 162

[12] Ibid, 163-166.

[13] Deborah Cowen. Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method Urban Geography, 41:4, 469-486, 2019 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02723638.2019.1677990?needAccess=true, 480.

[14] Bagnato, Footpaths to freeways, 2.

[15] Adam J. Barker. The Contemporary Reality of Canadian Imperialism: Settler Colonialism and the Hybrid Colonial State. American Indian Quarterly, University of Nebraska Press, 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40388468, 333.

Bibliography

Bagnato, Sharon. And Shragge, John. Footpaths to freeways: the story of Ontario’s roads: Ontario’s bicentennial 1784-1984. Downsview, Ont: Ontario Ministry of Transportation and Communications, 1984

Barker, Adam J. The Contemporary Reality of Canadian Imperialism: Settler Colonialism and the Hybrid Colonial State. American Indian Quarterly,University of Nebraska Press, 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40388468

Beiser, Vince. The world in a grain : the story of sand and how it transformed civilization. Riverhead Books, 2018

Cowen, Deborah. Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method Urban Geography, 41:4, 469-486, 2019 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02723638.2019.1677990?needAccess=true

Hutton, Jane. Reciprocal Landscapes, Stories of Material Movements. Routledge, 2019

Longfellow, Rickie “Back in Time: Building Roads,” Highway History, Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/back0506.cfm5

M’Dougall, WM. Information for Immigrants, Settlers and Purchases of Public Lands, With Maps, Showing The Newly Surveyed Townships, Colonization Roads, &c, of Canada. Hunter, Rose & Lemieux, 1862

The Ministry of Transportation 1916-2016: A history, Ontario Ministry of Transportation, accessed 15/02/2021, http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/about/mto-100/index.shtml

Murray, Derek. Equitable Claims and Future Considerations: Road Building and Colonization in Early Ontario, 1850–1890, Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, Volume 24, Number 2, 2013, https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/jcha/2013-v24-n2-jcha01408/1025077ar.pdf

O’Flaherty, C. A. and Boyle, Andrew. Highways, Fourth Edition. Elsevier, 2002.

St. John, Michelle. Colonization Road, CBC Television, 2016, https://gem.cbc.ca/media/firsthand/season-2/episode-9/38e815a-00b9abca4fc

Wynn, Graeme. Timber Trade History, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2013. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/timber-trade-history