The Bund, known as a historical and acclaimed strip of Shanghai’s riverfront, lends itself as a symbol of Sino-British relations and a shift in its Chinese architectural identity. Amongst the many tourist hot spots, The Bund iconizes itself as a “must see” destination both in historical and contemporary contexts. Littered with displaced architectural styles, buildings vary from Baroque, Gothic, Classicism, Romanesque, and Renaissance typologies. The preservation of these architectural phenomena amongst the Chinese fabric as bait for tourism speaks to the relic left through western imperialism. These styles provide the viewer with an explicit understanding of the presence and mark left by Western superpowers such as the British and French. Beyond a unique streetscape, The Bund is a spatial reminder of colonial legacy and social impositions following the Chinese loss in the First Opium War of 1839 with the British. This imperialist movement meant a social system of exclusion and exploitation by western powers to which it has imprinted the environments of Asia’s riverine and costal ports. The Bund is direct manifestation of colonial empire through the imperial processes of visual mediums. Done through architectural manipulations, skewed self-identity, tourism, and western power structures, The Bund lends itself an abrupt western nostalgia amongst the Chinese landscape.

Prominence of site as a Treaty Port still intact

The Treaty of Nanjing of August 29, 1842 [1], aids in contextualizing the Sino-British relationship and as a turning point in China’s treaty ports. Following China’s defeat in the First Opium War, against the British, many demands were imposed on the Chinese government through this treaty signed in the city of Nanjing[2]. An excerpt from the treaty details that,

“His Majesty the Emperor of China agrees the British Subjects, with their families and establishments, shall be allowed to reside, for the purpose of carrying on their commercial pursuits, without molestation or restraint at the Cities and Towns of Canton, Amoy, Foochow‐ fu, Ningpo and Shanghai, and Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain […] It being obviously necessary and desirable, that British Subjects should have some Port whereat they may careen andrefit their Ships, when required, and keep Stores for that purpose”.[3]

A historically well-known condition within this Treaty included China’s debt to Britain of ceding the territory of Hong Kong along-side the establishment of a fair and reasonable tariff.[4] Additionally, to these conditions, British Merchants were granted the permission to trade at five ports rather than just the South China port of Canton, this including Shanghai.[5] With this allowed for god like exemptions where citizens of with a high-ranking nation status were excused from Chinese legal jurisdiction.[6]

Prior to the British settlement and French concession, what is now known as The Bund was described by Chinese tourism sites as, “The Bund was nothing more than a muddy riverbank covered in reeds. Eventually, the area became a British settlement and in 1846, Shanghai was deemed an important trading port”.[7] It is important to note the terminologies used to describe the initial state of this historically significant site in Shanghai and what is now the face of Shanghai tourism. The use of the words “nothing more than” immediately reduces the significance of the site prior to the British imperialist processes that built up what The Bund is today. As a site which promotes Chinese tourism, it speaks volumes to the colonial legacy left by the British in which the original Chinese identity of the site is disregarded to monumentalize the extravagance of western architecture. The sequence of that sentence must also be noted. The claim of Shanghai as an important trading port as a product of British settlement sets the bar to westernization as the standard and bestows the power to them. It muddles the identity of Chinese landscapes and places the western landscapes in high regards.

Colonial architectural styles dominating the site

Shanghai’s architectural transformation along its waterfront reflects the significance placed on this principal entrepot between Western powers (Britain) and China. Its transformative state quickly put the Bund on a pedestal, as a nexus of trade and finance for Shanghai.[8] The Bund’s architectural evolution could be understood through three successive waves of renewal. Between the 1850s to early 1870s, the Bund skyline could be catalogued with one to two storey buildings that struck the landscape not by height but by their aesthetics.[9] The third wave of construction was where the prominence of Western style of architecture dominated this Chinese landscape. Consisting of primarily commercial compounds, called hongs, these building typologies reserved the back rooms and upper floors for accommodations and the ground floor as office spaces.[10] Mimicking our current understanding of multi-use buildings often found in condominiums downtown. The turn of the nineteenth century brought forth “modern” construction and a wider range of programmatic integration into the Bund. During this time, the banking presence along the Bund became more prominent whereas the treaty ports original purpose to host the loading and unloading of ships began to disperse.[11] By the 1930s, the Bund was at the apex of its development with its “billion-dollar skyline” and an agglomeration of industrial, financial, and mercantile powerhouses.[12]

This transformative waterfront was a demonstration of an insurgence of power and an establishment of a colonial empire in China. Becoming an architectural monument for the locals and a moment of nostalgia for foreign travellers, the Bund has become and remains and icon that neither fully westernized nor fully Chinese. Embracing architectural styles most commonly found in the west, the Bund’s skyline disrupted and continues to disrupt the Chinese landscape, demanding to be seen. The perceptions of the Bund from both perspectives of locals and western biases could be thoroughly understood by tourism excepts and travel reviews from the early twentieth century. Heriot summarizes these two contrasting perspectives as, “while the former [western] wrote about it as an ode to their accomplishment in Shanghai, the latter [local] used it to convey a sense of urban modernity”.[13] This quote aids in understanding this skewed sense of identity in Shanghai in architectural theory. It sets the pedestal that Western architecture is a reflection of what is “current”, “desired”, and “well-mannered”. Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher’s “History of Architecture brushes on the topic of “the other” in context to western, primarily European, architectural history. Where they hold themselves in such high regard, that anything of non-conformity is seen as “the other” or “grotesque”. These self-absorbed values manifested itself into the Chinese urban fabric and skewed their importance of placed based architecture. What is “modern” is now a series of displaced architectural styles that have no necessity of being present in this landscape. However, its presence forcibly demands for the juxtaposition amongst the Shanghai skyline for both local and foreign understanding of power.

Juxtaposition of Colonial relics with contemporary city high rises

Its presence is an architectural monolith that encapsulates the whole city in such a fraction of the area. This disregard for the original Chinese landscape and identity. As the Bund gained more traffic for foreign (western) travel, the original site conditions to which the British sought after began to recede in the background to the empire that was built. The Bund in in itself possessed its own identity, separate from the context of Shanghai and by extent China. Chris Henriot’s text describes various travel excerpts from British travelers that were shocked that there were Chinese culture and/or people in Shanghai, and especially on the Bund. The British obsession in “elevating”, and more accurately, colonizing the world gives way for a naïve and close-minded understanding of what is beyond the British empire. Shanghai became just another city within Great Britain, an extension of its geography. For what is The Bund is no longer, “just Chinese” but a manipulation to believe that it is in fact better and is what shall represent the city of Shanghai.

Through the visual medium of architectural invasions, the Bund was a product of imperial processes that has marked the Chinese landscape as a colonial relic for tourism of the past and present. Though the specifics of architectural spatial organization, façade ornamentation, or urban planning was not discussed specifically, it is important to understand how the Bund as a commodity for British imperialism. Its romanticization of the past and present reflects its western counterparts as the “Paris of China” and “Wall-Street of China”. As the shear presence of baroque architecture directly correlates with love and finance with the hustle and bustle of Wall Street. To make these comparisons insinuates the inability to understand The Bund without the prior establishment of a western context. The British Empire is built upon the urgency to find nostalgia in parts of “the other”, the worlds of the grotesque and unfamiliar. To reduce its cultural significance and skew their own sense of identity to believe their imposition is what is civilized and “modern”. Understanding the Bund in today’s context does not differ from the past that greatly. As bait for tourism and the face of Shanghai, the colonial legacy of British imperialism remains, and their relics have continued to be monumentalized for the sake of capitalism and aesthetic.

Endnotes

[1] Samuel Y Liang, “Where the Courtyard Meets the Street: Spatial Culture of the Li Neighborhoods, Shanghai, 1870–1900,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 67, no. 4 (2008): 48.

[2] “The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment: Asia for Educators: Columbia University,” The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment | Asia for Educators | Columbia University, |PAGE|, accessed February 17, 2021, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/china_1750_opium.htm#treaty)

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Cary Y. Liu. “Encountering the Dilemma of Change in the Architectural and Urban History of Shanghai.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians73, no. 1 (2014): 118.

[7] “The Bund, History, Interesting Facts, Culture, Tours,” Sublime China, |PAGE|, accessed February 17, 2021, https://sublimechina.com/attraction/the-bund/)

[8] Christian Henriot, “The Shanghai Bund in Myth and History: An Essay through Textual and Visual Sources,” Journal of Modern Chinese History 4, no. 1 (May 26, 2010): 11.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 12.

[11] Ibid., 15.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 24.

Figures List

Feature Image

“Geographical Locations.” Inside Dreams of Joy. Accessed February 04, 2021. https://www.lisasee.com/dreamsofjoy-inside/geographical-locations/.

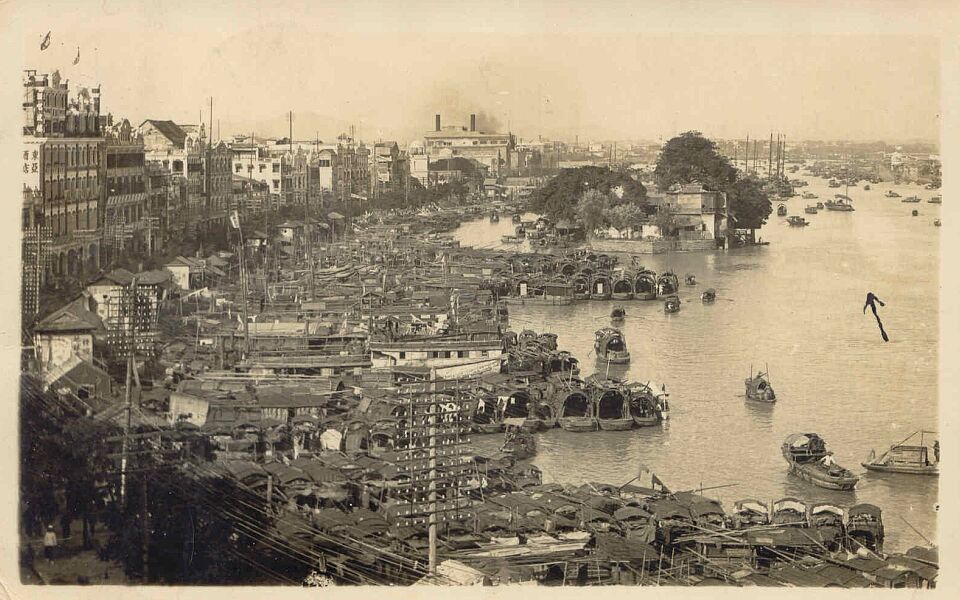

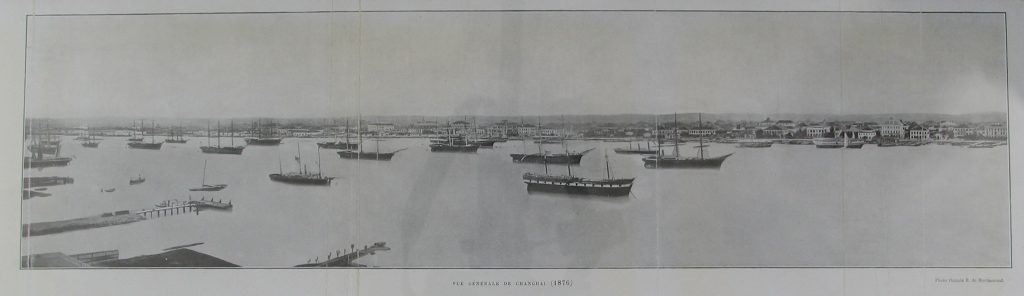

Figure 01 |

Henriot, Christian. “General View of the Bund – 1873: Virtual Shanghai.” General View of the Bund – 1873 | Virtual Shanghai. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.virtualshanghai.net/Photos/Images?ID=17618.

Figure 02 |

“Geographical Locations.” Inside Dreams of Joy. Accessed February 04, 2021. https://www.lisasee.com/dreamsofjoy-inside/geographical-locations/.

Figure 03 |

“Geographical Locations.” Inside Dreams of Joy. Accessed February 04, 2021. https://www.lisasee.com/dreamsofjoy-inside/geographical-locations/.

Works Cited

Cary Y. Liu. “Encountering the Dilemma of Change in the Architectural and Urban History of Shanghai.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians73, no. 1 (2014): 118-36. Accessed January 28, 2021. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.1.118.

Henriot, Christian. “The Shanghai Bund in Myth and History: An Essay through Textual and Visual Sources.” Journal of Modern Chinese History 4, no. 1 (May 26, 2010): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535651003779400.

Horesh, Niv. “The Bund and Beyond: Rethinking the Sino-Foreign Financial Grid in Pre-War Shanghai.” China Review 7, no. 1 (2007): 1-26. Accessed January 28, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23461863.

Jeremy E. Taylor. “The Bund: Littoral Space of Empire in the Treaty Ports of East Asia.” Social History 27, no. 2 (2002): 125-42. Accessed January 28, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4286873.

Liang, Samuel Y. “Where the Courtyard Meets the Street: Spatial Culture of the Li Neighborhoods, Shanghai, 1870–1900.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 67, no. 4 (2008): 482-503. Accessed February 17, 2021. doi:10.1525/jsah.2008.67.4.482.

“The Bund, History, Interesting Facts, Culture, Tours.” Sublime China. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://sublimechina.com/attraction/the-bund/.

“The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment: Asia for Educators: Columbia University.” The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment | Asia for Educators | Columbia University. Accessed February 17, 2021. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/china_1750_opium.htm#treaty.