The Potala Palace is a magnificent structure built in Lhasa, China, and was finished and opened in 1649, where it served as the home to the Dalai Lamas. Unexpectedly, the palace holds a dark history of power struggles with China as conflicts arose that deemed the Tibet government a culprit to abolish the government. Though the palace was an important political and sacred strength in the 1600s, it is now a museum and World Heritage Site. Built with the massing of a fortress, the palace consisted of thick, painted brick walls and characteristic golden roofs that prompted it to draw attention to the peak of the mountain.[1] With the structure and narrative in mind, this text aims to reflect upon the political power dynamics between the Potala Palace and the Chinese government. It begins to explore the conflict that influenced the framework of society, and how this shift has been carried over history into modern society. Thus, this analysis can begin to provide an introspective lens into understanding how societies transform under the influence of symbols of power in architecture and social values.

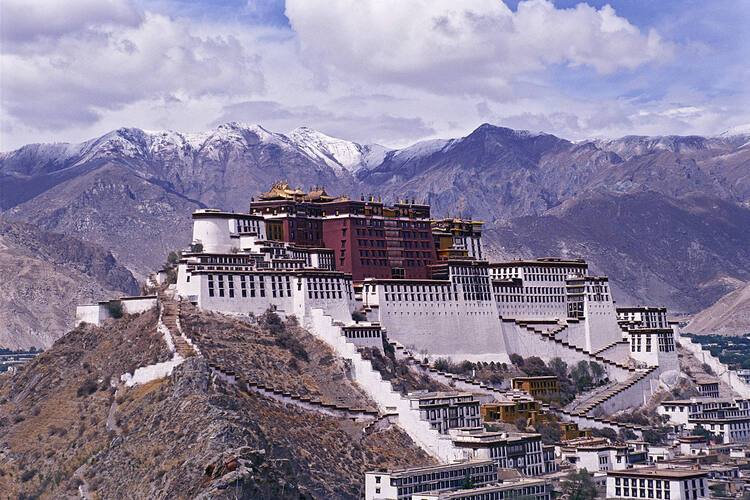

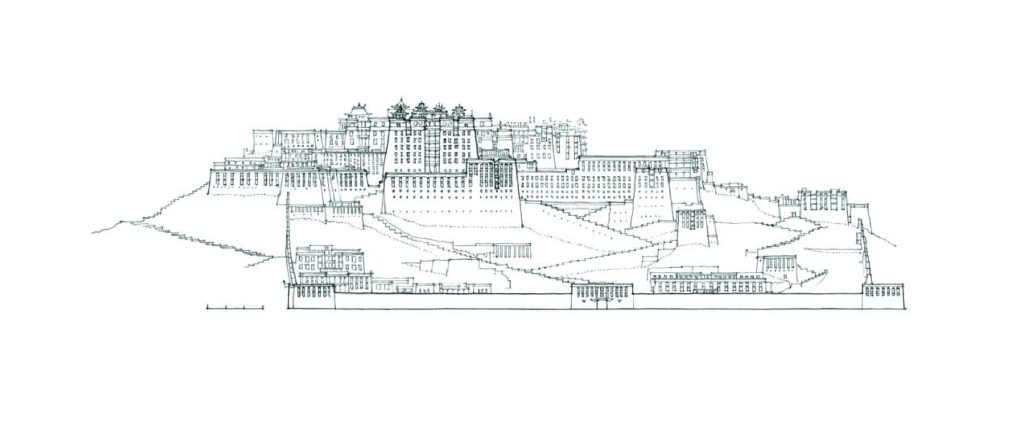

Like many temples and places of worship, the architecture is an astounding sight. The prominent structure of the Potala Palace scales along a mountain that sits with a backdrop of larger mountains. The walls appear to be impenetrable but yet slopes in compliance with the mountainous geography. Likewise, the location begins to suggest the grandeur of the structure, as if to reinforce the significance by having it rest on a mountain top. The landscape consists of dried shrubs and vegetation, spread with yellow brushes, carved out by the zigzag stairways that connect the peak of the palace to those below living in the and area called the ‘Cultural Palace of Working People’ where governmental buildings and residents were built.[2] In this organization, the design begins to reinforce the hierarchies of power; those who are of spiritual and political advantage will reside within the palace, while the rest would reside at the base of the mountain. Despite the intention to act as a spiritual sanctuary, the Potala Palace encompasses the contrasting narrative of political turmoil that tells the story of both spiritual and political power. As such, the Potala Palace became a strong and hopeful guide to life in Tibet; it was a place where citizens could look up to for spiritual guidance while understanding that the political leaders were also characters of importance in their society. The seemingly impenetrable walls of this castle suggested to its people that they could have a strong and sturdy life. In much of these descriptions, the architecture begins to silently implement this hierarchy of power, using its form and organization to impose values.

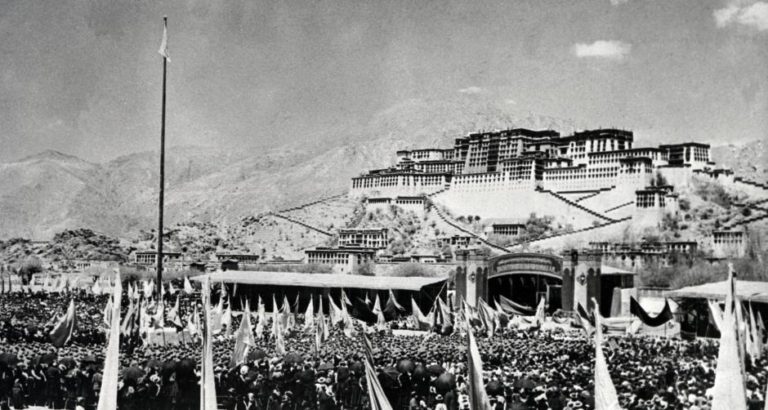

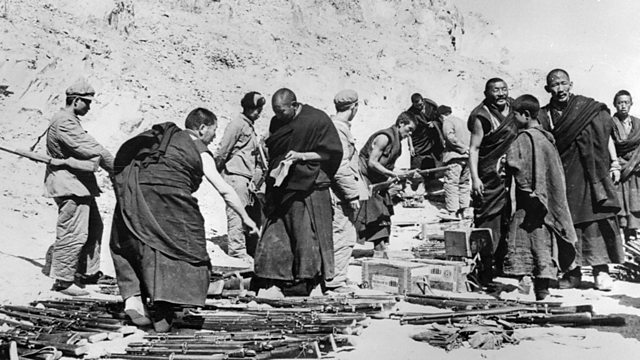

In Tibetan culture, the idea that living as a believer of Buddhism will establish a life of harmony garnered much support, even from Yu Wenliang and Liu Deshen, who were Christian leaders.[3] As Tibet culture is centered on religion, much of their way of life involved rituals that connect the physical and spiritual realm, to uphold this idea of a harmonic, perfect world.[4] Unfortunately, the peaceful life of the Tibetans abruptly ended in 1959. Since the 15th century, the Chinese government has kept a close eye on the Tibetans. Though they supported and practiced Buddhism, the monarchs and leaders had always made sure to be cautious and ensured that the regions outside of the capital obediently followed Chinese laws.[5] Thus, once the Tibetans demonstrated a sense of opposition following the communist rule of Mao Zedong to fight for socialist reform, the Chinese government sent soldiers to stop the plans of the Tibet uprising. Unfortunately, due to the masses of armed soldiers, the Tibetans did not have a choice but to surrender. With monasteries damaged and Buddha statues destroyed, the fate of Potala Palace seemed grim. Yet shockingly, its grandeur as an architectural masterpiece saved it from its demise as a structure, though its pride and image were completely stripped. As a result of this mercy on the palace, the Chinese government used the Potala Palace as a backdrop to hang Mao Zedong’s portrait, evidently reinforcing the domination of Chinese rule.[6]

One of the reasons behind the violence on Tibet stemmed from the fact that Mao found religion as something poisonous, something that will impede the reign of communism.[7] As part of Mao’s attempt to create a better China, his objective was to enact erasure on the ‘old’ Tibet and to create a new homogenous society with the same ideals; though this view was radical and upsetting to many, Mao had many supporters because it promised equality in both men and women. In many ways, Mao’s belief in communism, the equality for all, resonated with a large population, which allowed for his extended time of reign. Similar to western approaches to colonialism, Mao’s ideals were often painted in a certain way to achieve his idea of sublime and what it meant to have a perfect population and way of life. However, his tyrannical outlook, the fact that much of his exploits were to ensure the preservation of his political status, was kept secret from his supporters. And so ironically, Mao’s fear of losing power prompted him to irrationally initiate movements that resulted in a famine and both “financial and social bankruptcy” in China.[8] Subsequently, Mao’s downfall did not result in the restoration of Potala Palace. Instead, the acts of destruction of Tibetan culture paved a foundation where communist values are seemingly carried onto the present day whereby the political turmoil continues to taint the relationships between the Tibetans and the Chinese. In the end, Potala Palace in the present day is no longer a spiritual sanctuary. Instead, it has become a spectacle for tourism, events, and any activities involving economic gain. Within the walls today, over a hundred sculptures depicting the terrible events of the uprising are set on display as if performance to promote the power of the Chinese government.[9] Though its magnificent structure is still standing, the essence of this castle has been erased.

“On a visit to Tibet in 1979, Lobsang Samten, elder brother of the Dalai Lama, made this heartbroken remark as he looked at Potala Palace— still shining brilliantly under the sun, but not the same as before”

“The Decline of Potala Palace” by Woeser

The history of the Potala Palace is essential to understanding the narrative of empire and acts of colonialization even between those in the same country. At first glance, the palace may shine as a place of beauty and enlightenment but when examined closely, it is settled on a foundation of power struggles and violence, and it will always symbolize a scar in Tibetian history. Even today, China holds an indescribable amount of power amongst all its states, only beginning to suggest how these parts of the country are kept on a tight rein. Thus, this conversation of power is important when examining the Potala Palace, and offers a different perspective to understand how both architecture and social views can reconstruct formalities of power.

Footnotes:

[1] Ching, Jarzombek, and Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, 517.

[2] Woeser, Decline of Potala Palace, 45.

[3] Saxer, Re-Fusing Ethnicity and Religion: An Experiment on Tibetan Grounds, 187.

[4] Zhang and Tao Wei, Typology of Religious Spaces in the Urban Historical Area of Lhasa, Tibet, 386.

[5] Ching, Jarzombek, and Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, 516.

[6] Woeser, Decline of Potala Palace, 45.

[7] Saxer, Re-Fusing Ethnicity and Religion: An Experiment on Tibetan Grounds, 185.

[8] Zhang, The Political Leadership of Mao Zedong, 30-31.

[9] Woeser, Decline of Potala Palace, 46.

—

Bibliography:

Ching, Francis, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash. In A Global History of Architecture, 516–18. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2017.

Saxer, Martin. “Re-Fusing Ethnicity and Religion: An Experiment on Tibetan Grounds.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 43, no. 2 (2014): 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261404300210.

Woeser, B. “Decline of Potala Palace.” Chinese Rights Forum, November 2007, 44–51. (Originally posted online: Woeser, “Decline

of Potala Palace,” TibetWrites (September 2006), www.

tibetwrites.org)

Zhang, Donia. “The Political Leadership of Mao Zedong.” Journal of Contemporary Educational Research 2, no. 4 (2018): 28–33. https://doi.org/10.26689/jcer.v2i4.407.

Zhang, Yingzi, and Tao Wei. “Typology of Religious Spaces in the Urban Historical Area of Lhasa, Tibet.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 6, no. 3 (2017): 384–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2017.05.001.

—

Images:

Potala Palace Overview: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/707/

Section & Elevation: “A Global History of Architecture”

Uprising: https://www.contactmagazine.net/articles/uprising-day-remembered-around-the-world/

Disarming: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01584yt

Tourist: https://www.tibetanreview.net/china-reopens-tibets-potala-palace-for-tourists/