An Architectural Gesture of British Industrial and Imperial Omnipotence

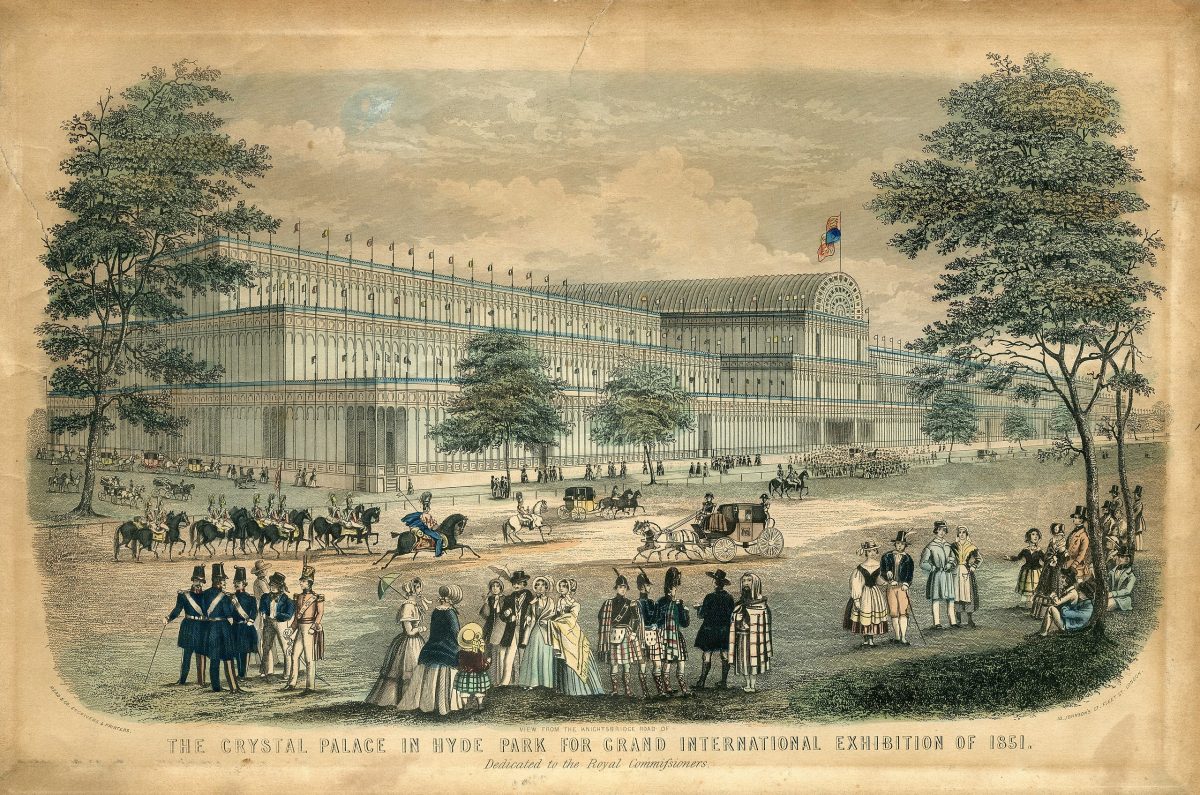

The Great Exhibition of 1851, also known as The Crystal Palace, located in Hyde Park, London, is generally referred to as a renowned architectural gesture of universal peace, welcoming accomplishments in science, technology, and industry.[1] It is known to have “emphasised the commercial importance of more than thirty colonies and dependencies whose manufactures and raw materials were displayed.”[2] The Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton, has “stood as the leading symbol of the mid-Victorian era, symbolizing peace (in international affairs), progress (socially, politically, technologically), and prosperity (in economics).”[3] It was therefore implemented in an effort to extend Britain’s cultural reach. In contrast to this perception, in reading multiple interpretations of this progressive event, it is apparent that this building paid a contribution to affirming Eurocentric values through the exertion of British industrial and imperial omnipotence. Not only did this exhibition allow for global networks of exchange, it also contributed to the global expansion of Victorian assimilation. While the innocent intention spoke to Britain’s display of global unity, it ultimately resulted in a clear and utter distinction between civilized and savage/European and other. This will be affirmed through the exploration of the intention versus the result of the exhibition by analyzing key efforts of showcasing including Eurocentric dominant ideologies, racial inequality as well as social and political power dynamics.

Britain’s ultimate and advertised efforts of The Crystal Palace posed to unite the global population, people of all kinds, and celebrate the progress of humankind. Through this British led endeavour would come a united front of cultural bodies allowing for new ways to feed into and infiltrate these surrounding capitals. From its inception, the intentions of Britain came across as pure and subtle, however, it is difficult to oppose an actual truth of rationale in which Britain could come to influence the non-European world after the image of Victorians. The Great Exhibition has been further analyzed “as a cartographic validation of free trade’s new world order, setting out an Anglocentric industrial and cultural mission at the same time as it further opened up the world to British hegemonic ambition.”[4] This globally discussed building would not only allow Britain to showcase its superiority in regards to industrial development, but also allow it to exert global rule and pre-eminence. Paul Young’s Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition indicates the underlying intentions of Britain’s so-called pure motives:

What emerged at the Crystal Palace was the notion of a mission which elided metropolitan gain with an unselfish belief in the idea of regeneration. This was not a conquest of the earth, but rather a means by which those inhabitants of the world with ‘a different complexion or slightly flatter noses’ than their Victorian counterparts could be reunited with the earth and their Western relatives in productive and progressive ways. Furthermore, the process of economic elevation was presented not simply as an opportunity to enrich the world materially, but also to enlighten non-Europeans culturally.[5]

It is seeming that while the Crystal Palace encouraged a united front, it desired this united front to follow under European practices and rule, and ultimately under European tradition, culture and values. This in turn would allow Europe to take on the role as the all-seeing, all knowing, and most powerful body amongst the globe.

The acts of Britain’s united intention were implemented through segregation and dissociation. Through observation and commentary on the exhibit, it is apparent that The Crystal Palace was instrumental in racialized and xenophobic representations, further creating a clear divide amongst an event that was intentioned to unite.[6] During this time period, Britain played a contributory role in the construction of global inequality “along lines of colour as well as cultural difference, and eradicated millions of those peoples.”[7] The representation of non-Europeans in commentary of the exhibition “reveals a mindset which not only justified such exploitative trading relationships but sanctioned the violence which accompanied them”.[8]

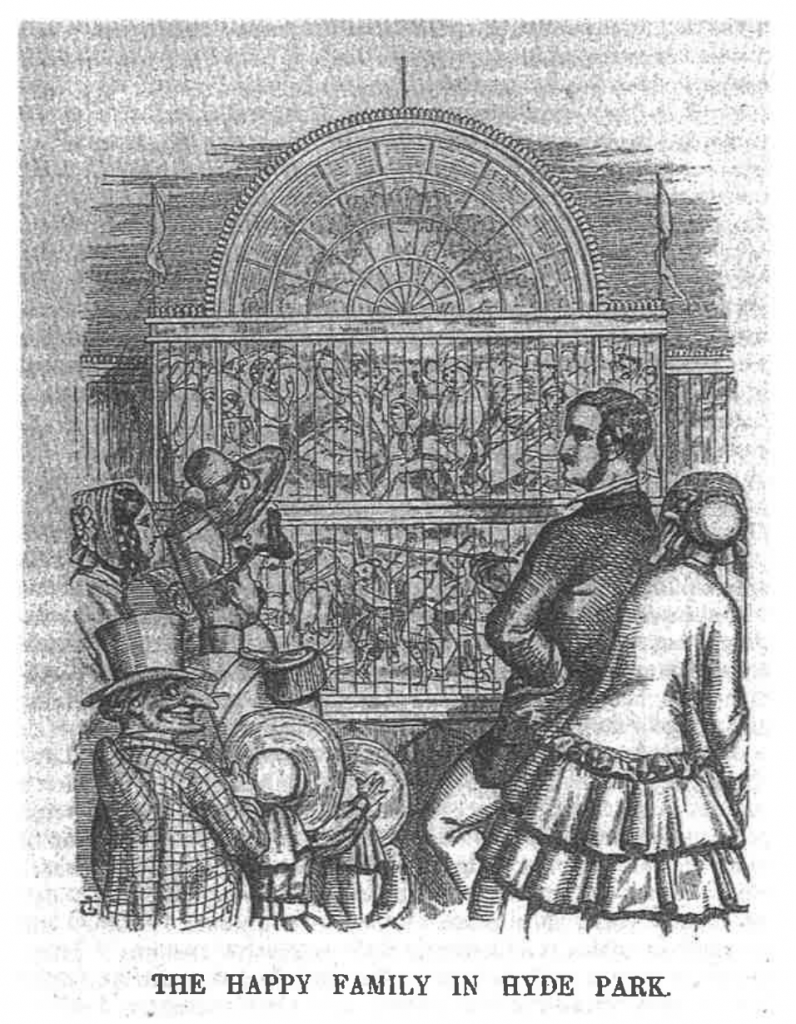

In “Empire Under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851-1911,” Jeffrey Auerbach touches upon the piece, “The Happy Family in Hyde Park.” He refers to the image as “a clear demarcation between the Europeans…and the foreigners”.[9] This image contributes to not only the ways in which this exhibit was represented, but also the ways in which it was interpreted. It allows the Victorian viewer to not only internalize a clear separation between Europeans (standing outside the building) and foreigners (located inside the building) but also depicts the foreigners as the observed, the performer, the entertainment. This affirms the notion that Europeans have the control to watch over and showcase their empire, ultimately inheriting the world’s accomplishments as their own accomplishment. On top of this, the dynamic depicted works to displace and exoticize non-Europeans, further sustaining and reaffirming their title as ‘other’.

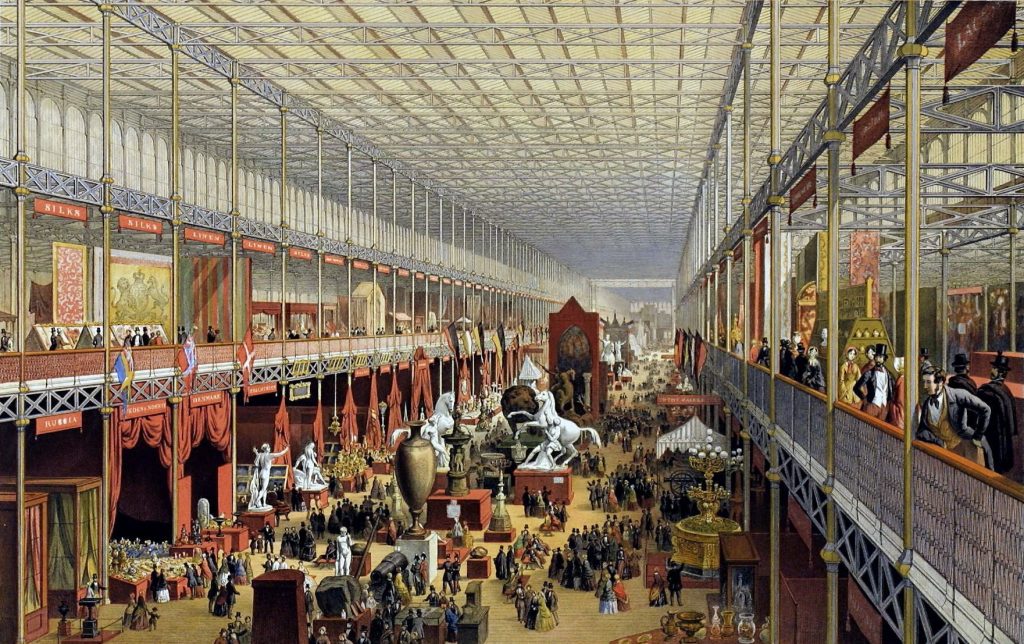

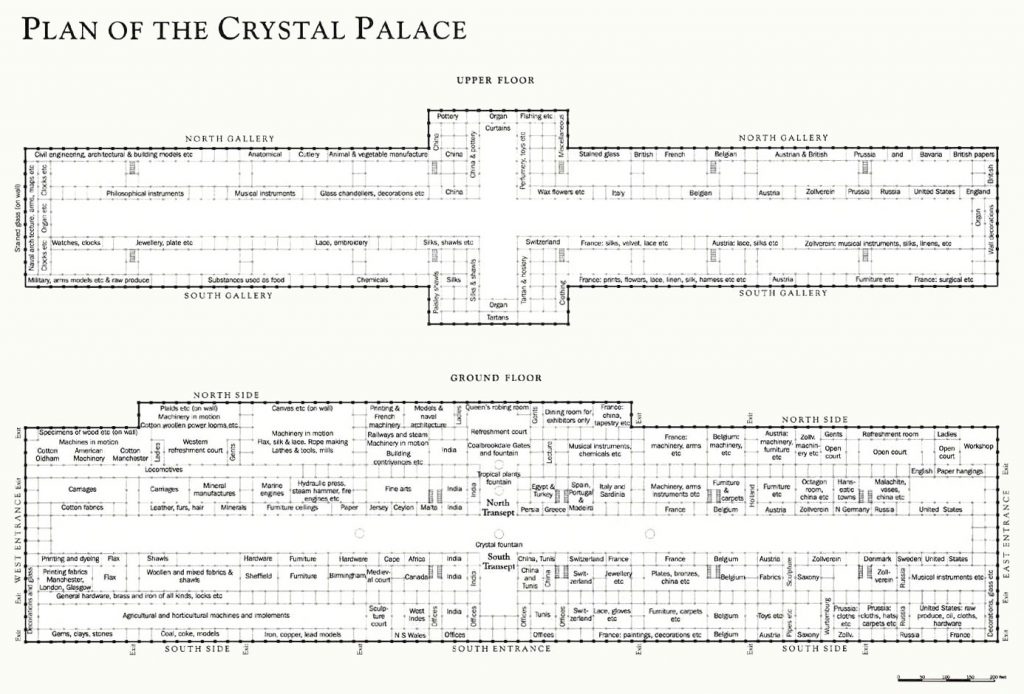

The Crystal Palace, furthermore, created a space that congregated various nations, however, each nation was clearly categorized and distinguished from one another in its design. Rather than showcasing a collective body, each nation was distinguished, in turn separating one nation’s progress from another.[10] However, what is valuable to recognize “is not so much the particular categorizations into which these ‘backward’ peoples were seen to fall, so much as the idea of the Palace as a global chart of things which established the West, and particularly Britain, as the ‘Bearer of Progress.’”[11] This separation further deemed non-European nations as rendered dependent upon their European and civilized counterparts.[12] This permitting Europeans to maintain a hierarchy amongst human life. The Crystal Palace was “not simply a cultural event aimed at education and enlightening, but a purveyor of coded messages about the alleged racial superiority of European civilization.”[13] It primarily served to satisfy the Victorian visitor hence, racial biases persisted throughout.

Ultimately, The Crystal Palace poses an example of the use of architecture as a didactic tool to relay information regarding culture, technological progress and historical significance, in which ultimately empowered European authority to penetrate. The simple acts of architecture can come together to have a major impact globally, in this case, to unite as well as conquer. This architectural piece provided a territory to conceive a manifestation of hierarchy, which was further embellished through subtle acts in design, organization and tactic of display. Overall, “the Exhibition’s rationale, was to create a world after the image of the Victorians.”[14] While it is melodramatic to assume The Great Exhibition instigated all Eurocentric domination, this structural body definitely had an agenda as well as an impact on its repertoire of visitors in regard to the supremacy of Victorian culture. The Great Exhibition “can no longer stand for the peace, progress, and prosperity that did not exist,” it should be regarded for the characteristics of the mid-Victorian era including xenophobia, aristocratic power, division of societal classes, as well as “the entrenchment of racial attitudes that would characterize the expanding British empire.”[15] In the grand scheme, acts of colonization led to the bloated egos of Victorians further resulting in imperial dominance. This inherently showcases colonizers efforts to demonstrate the exertion of power through the use of architecture.

Notes:

[1] Geoffrey Cantor. “Science, Providence, and Progress at the Great Exhibition.” Isis 103, no.3 (2012): 439.

[2] Tim Barringer. “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project,” in Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, ed. Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn (London: Routledge, 1998), 12.

[3] Jeffrey Auerbach. “The Great Exhibition and Historical Memory.” Journal of Victorian Culture 6, no.1 (2001): 107.

[4] Paul Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” In Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851, ed. Jeffrey A. Auerbach and Peter H. Hoffenberg (Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2008): 5.

[5] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 17.

[6] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 6.

[7] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 6.

[8] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 6.

[9] Jeffrey Auerbach. “Empire Under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851-1911,” in Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire, ed. John McAleer and John M. MacKenzie (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2015): 117-119.

[10] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 12.

[11] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 13.

[12] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 12.

[13] Auerbach. “The Great Exhibition and Historical Memory.”: 98.

[14] Young. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” 17.

[15] Auerbach. “The Great Exhibition and Historical Memory.”: 107-108.

Bibliography:

Auerbach, Jeffrey. “Empire Under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851-1911,” in Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire, edited by John McAleer and John M. MacKenzie, 111-141. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2015.

Auerbach, Jeffrey. 2001. “The Great Exhibition and Historical Memory.” Journal of Victorian Culture : JVC 6 (1): 89-112

Cantor, Geoffrey. 2012. “Science, Providence, and Progress at the Great Exhibition.” Isis 103 (3) 439-459.

Barringer, Tim. “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project,” in Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, edited by Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, 11–27. London: Routledge, 1998.

Young, Paul. “Mission Impossible: Globalization and the Great Exhibition,” In Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851, edited by Jeffrey A. Auerbach and Peter H. Hoffenberg, 3-25. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2008.

Images:

Cover Image: Read & Co. Engravers & Printers, View from the Knightsbridge Road of The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park for Grand International Exhibition of 1851. Dedicated to the Royal Commissioners., London: Read & Co. Engravers & Printers, 1851.

Figure 1: McNeven, J., The Foreign Department, viewed towards the transept, coloured lithograph, 1851. Prints, Drawings & Paintings Collection, V&A South Kensington. Great Britain: 1851.

Figure 2: Tennial, John, The Happy Family in Hyde Park. July, 1851. In “Empire Under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851-1911.” Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2015.

Figure 3: Plan of the Crystal Palace. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Crystal_Palace