The concept of western entities occupying, governing, and exploiting natural resources and native people from “foreign” places around the world has been heavily documented in the relation to sugar and cotton plantations however, similar practices were and still being executed in a wide range of fields. In 1899 the United Fruit Company was formed, being one of the first major company to make bananas widely available in America. Their roots grow deep as they established multiple plantations, and dedicated railroads and shipping lines for the sake of American capitalism. The professor Geoffrey Jones “The Controversial History of United Fruit.” podcast. To appreciate the living experience of the enclaves, Laura Sibert’s “Who’s the Top Banana?: Corporate Institutionalization of Race and Mobility in Central American Banana Enclaves of the Twentieth Century,” which is key to understanding the racial and spatial segregation. Lastly, Jason M. Colby’s “Banana Growing and Negro Management,” to help draw similarities between the sugar and cotton plantations to the banana plantations and how the business scheme the United Fruit company followed piggybacked off the wrong doings of early colonialism; consequently creating a new wave of slavery. Through the exploration of the resort like conditions of the settlement towns in juxtaposition to the realities of the working plantation, an understanding of the influence and power companies were able to obtain is recognized.

The Power of the Banana

The banana’s official debut in North America was at the World’s Fair in 1876. For most people, it was their first encounter with the distinguished fruit. Americans viewed the exotic fruit as being the quintessence of upper-class privilege. Though its rise to fame grew exponentially, its dark histories and ties to colonialism were concealed till much later. When thinking of historical colonialism one might believe settlers were unaware of the implications and dangers of their actions. They had bright intentions of bettering the lives of those deemed “uncivilized” by bringing new developments, religion and education. However, in the case of The United Fruit Company, they took advantage of areas which were previously occupied by the Spanish in the 16th century where they “ruled over the descendants of the Mayans who were in terrible conditions of poverty and illiteracy employed virtually as slaves.… Spanish colonial regime was overthrown, and this white elite established themselves entirely running the country.”1 Instead of assisting those in need, they viewed this as an opportunity to build their empire upon the ruins of past civilization. The United Fruit Company strong-armed their way around Central America, destroyed natural habitats with mono crops, and enslaved the native population exposing them to toxic working environments. As bananas quickly became the biggest export for many nations, it resulted in a dependent relation of foreign interference, thus giving these companies immense power not only over their working domain but governments as a whole. These companies exercised power over mass amounts of land, infrastructure, capital and an entire market thus gave them the ability to restructure colonial economies to satisfy the needs of an American operation. Their dominating presence governed the course of countries and Central America as a whole, a term often referred to “banana republics.”

1 Jones, Geoff. “The Controversial History of United Fruit,” (20:06) Cold Call, HBR Presents, July 02, 2019. 5:08.

The Banana Resort

Though slavery was no longer formally practiced, its methods were still implemented as “They [United Fruit] also believed that racial hierarchy and segregation were essential aspects of labor control… reserving supervisory and clerical positions for whites and confining black workers to heavy plantation and stevedore work.”2 Higher ups simply viewed the workers as disposable cogs in the machine. This clear division between employers and employees, white and blacks and ladinos, was not only evident in the ranks and pay system but also in the living accommodations. Settler towns the United Fruit Company erected in the surrounding area were far removed from the harsh realities of the plantations. Demonstrating a case of a colonial power building settler towns as the architectural nodes within a system reproducing institutions of slavery.

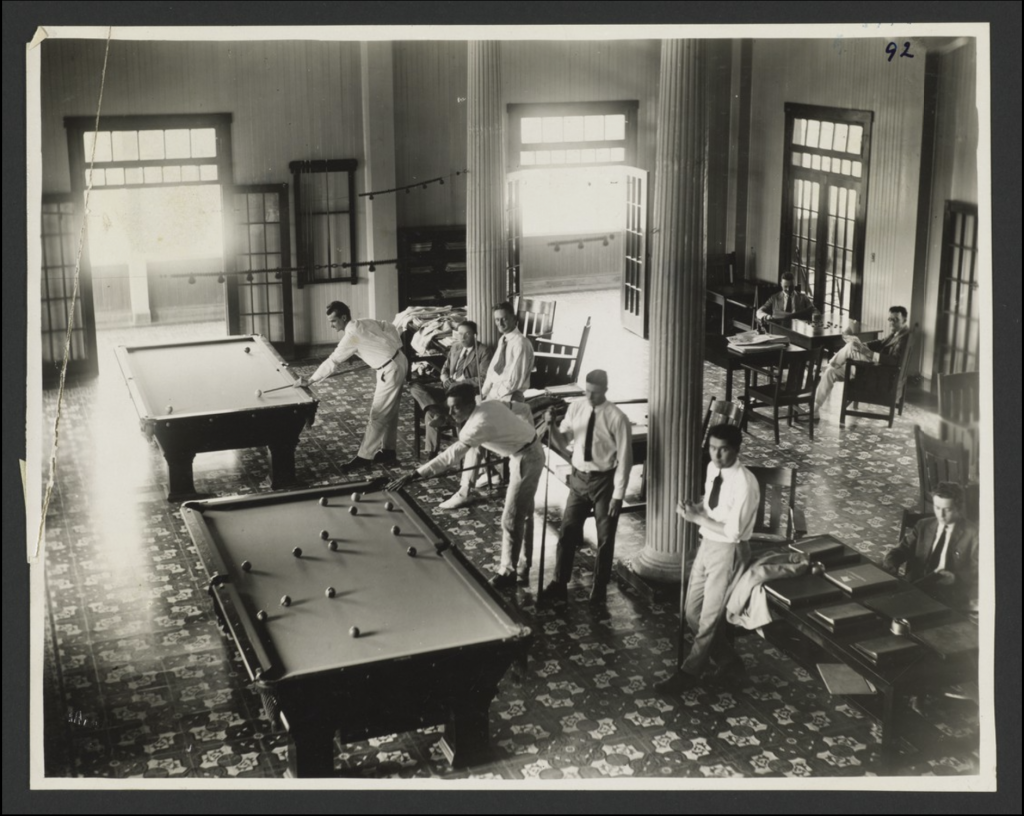

The racial segregation in these areas were blatant as dedicated housing for the highly-skilled workers brought from the United States were called “White Zones.” Tall western styled structures stood bleached and outlandish in the tropical landscape. The company established resort like conditions with tennis courts, billiard rooms, golf courses and ornate dinning halls with no intentions in allowing the black and ladino population to take part in. As Sibert 3 summarized, “In essence, the fruit companies intentionally recreated the picturesque upper-class American neighborhood within the remote jungles of Central America.” By showcasing the luxuries of upper white class, it widened the economic and racial gap between the white managers and the coloured workers. Physical obstacles, including fences, barbed wires and patrolling guards further reinforced the racial and spatial segregation.

Where one’s social hierarchy in relation to their perceived importance to the company was reflected in the provided housing. Executive personnel resided in these White Zones with pristine single-family houses, while “the native Latin American workers in the camps live in barracks, separated into single family dwellings.” The social hierarchy present in the construction of the towns was enacted upon as Colby 4 represented, the inequalities permeate the medical care system as modern hospitals were built to prioritize medical concerns that “threatened white immigrants, such as malaria and yellow fever. In contrast, illnesses common among labourers, such as tuberculosis and pneumonia, received little attention.” There was even unfortunately reluctancy to admit workers of colour but if so “within the facility itself, white patients were segregated from blacks and ladinos.” 5

2 Colby, Jason M. “‘Banana Growing and Negro Management’: Race, Labor, and Jim Crow Colonialism in Guatemala, 1884–1930.” Diplomatic History, vol. 30, no. 4, 2006, pp. 608

3 Sibert, Laura. “Who’s the Top Banana?: Corporate Institutionalization of Race and Mobility in Central American Banana Enclaves of the Twentieth Century” December 16, 2011. pp 7.

4 Colby, Jason M. “‘Banana Growing and Negro Management’: Race, Labor, and Jim Crow Colonialism in Guatemala, 1884–1930.” Diplomatic History, vol. 30, no. 4, 2006, pp. 609

5 Colby, Jason M. “‘Banana Growing and Negro Management’: Race, Labor, and Jim Crow Colonialism in Guatemala, 1884–1930.” Diplomatic History, vol. 30, no. 4, 2006, pp. 610

Where the Bananas Grow

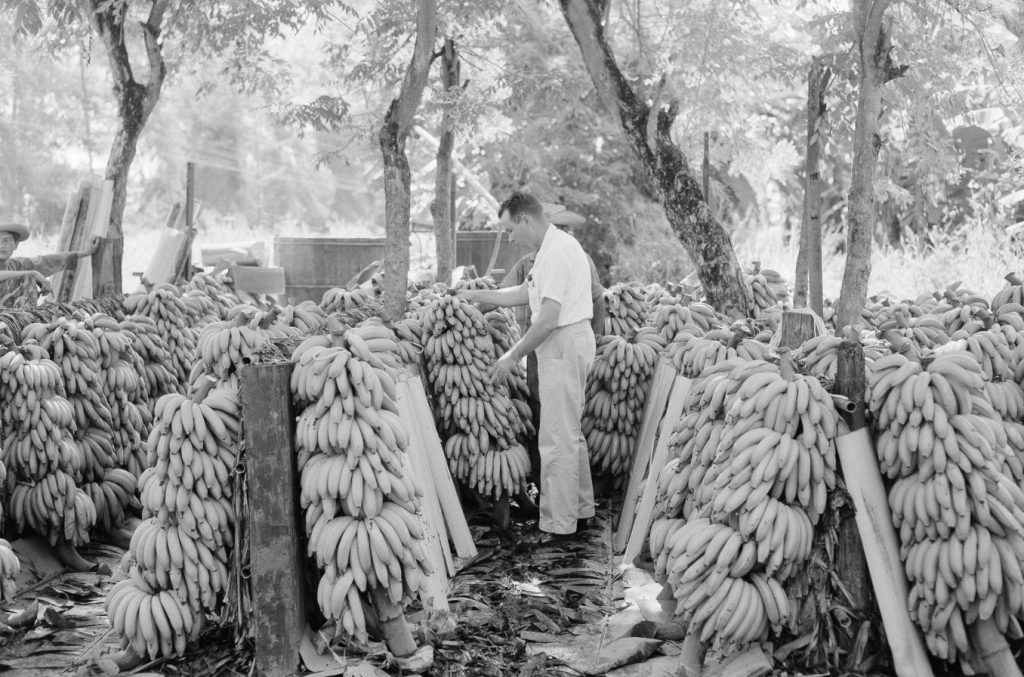

In contrast to the living quarters which empathized on the socializing and recuperating of the white population, the plantations were stringent and bare. Owing to the fact that bananas once harvested have a short timeline before going rotten. Therefore the chain of events from harvesting to shipping were as efficient as possible. The workers constantly travelled from farmland to rail carts. As depicted in figure 4, the social hierarchy is represented in the physical arrangement of subjects. Three white men wearing suits standing and sitting atop the railroad car supervising the hardworking coloured men below. This is also represented in figure 5, the white supervisor mounted on the horse while coloured workers cary bunches on bananas on the side. Though the company invested in building infrastructure to expedite the harvested bananas, the plantations were still considered manual resulting in a lot of heavy lifting.

Additional to the social hierarchy, pressing health concerns contributed to the already experienced malnutritions and poor health of the native population. The United Fruit Company had been practicing monoculture crops which were far more susceptible to pestilence, disease and major crop failure. 6 To flee disease, the company relied heavily and agrochemicals which jeopardized the health of the workers who spent lengthy hours in the crops exposed to the harmful chemicals. 7 This is problematic as it exhibits the lack of responsibility and regard the United Fruit Company has for its workers. They valued the continuous production and profits over the health of their workers. The company realized the harm they were inflicting yet still continued to use strong chemicals without any type of medical support or financial compensation.

The United Fruit Company’s plantations were no exception to colonial practices. Following the concept of a western entity occupying “foreign” land and exploiting natural resources for the benefit of their own commercial market. The fabrication of the company settlement towns registered the social hierarchy and racial segregation. This divide also permeated the work environment as the workers were employed virtually as slaves with white executives. Their domination of infrastructure, political and financial affairs still hold true today as the aforementioned plantations still exist. If anything, the stressors they face have grown due to increase of global demand and strained environmental conditions. Though the company’s history is surfacing and the workers’ best interests are being discussed, in many ways the companies roots and visions still remain intact.

6 “a potent cocktail called Bordeaux Mixture, which had the nasty side effects of turning workers’ skin blue and stealing their sense of smell and their ability to keep food down. It killed an unknown number of banana laborers.” Biuso, Emily. “Banana Kings. The history of banana cultivation is rife with labor and environmental abuse, corporate skulduggery and genetic experiments gone awry.” The Nation. February 28, 2008

6 Biuso, Emily. “Banana Kings. The history of banana cultivation is rife with labor and environmental abuse, corporate skulduggery and genetic experiments gone awry.” The Nation. February 28, 2008

Bibliography

Biuso, Emily. “Banana Kings. The history of banana cultivation is rife with labor and environmental abuse, corporate skulduggery and genetic experiments gone awry.” The Nation. February 28, 2008

Carlile, Clare. “The Story of Bananas: Banana Republics and Colonial Control.” Ethical Consumer Since 1989. February 20, 2020

COLBY, JASON M. “‘Banana Growing and Negro Management’: Race, Labor, and Jim Crow Colonialism in Guatemala, 1884–1930.” Diplomatic History, vol. 30, no. 4, 2006, pp. 595–621. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24915077.

Sibert, Laura. “Who’s the Top Banana?: Corporate Institutionalization of Race and Mobility in Central American Banana Enclaves of the Twentieth Century” December 16, 2011. Pp 1-24

Soluri, John. “Bananas Before Plantations. Smallholders, Shippers, and Colonial Policy in Jamaica, 1870-1910.” Iberoamericana (2001-), vol. 6, no. 23, 2006, pp. 143–159. JSTOR,

PODCAST: “The Controversial History of United Fruit,” (20:06) Cold Call, HBR Presents, July 02, 2019. https://hbr.org/podcast/2019/07/the-controversial-history-of-united-fruit

Images

Title Photo Loading bananas, Honduras 1926.United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, 1916-1927, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/pc/large/united-fruit.html

Fig. 1 New club house at Central Boston. 1924. United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, 1916-1927, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvgroup12724/urn-3:HBS.Baker.GEN:10707833/catalog

Fig. 2 United Fruit Company club house dinning rooms, 1924. United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, 1916-1927, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvgroup12724/urn-3:HBS.Baker.GEN:10707835/catalog

Fig. 3 United Fruit Company clubhouse, billiard and reading room,1924. United Fruit Company Photograph Collection. Baker Library Historical Collections. Harvard Business School.

http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvgroup12724/urn-3:HBS.Baker.GEN:10707834/catalog

Fig. 4 Manager’s House, United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, 1891-1962, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

http://www.library.hbs.edu/newsletter/archives/2005-11-spotlight.html.

Fig .5 6 room labor camp – $1,000,1932 United Fruit Company Photograph Collection. Baker Library Historical Collections. Harvard Business School.

http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvwork729885/catalog

Fig. 6 Loading bananas on a Train, Costa Rica, 1902, Krueger Family Paper, 1952-1991. Wendorf, William

https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM109538

Fig. 7 Bringing Fruit out to Loading Platform, Puerto Castilla, Honduras, circa 1920s. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvwork719694/catalog

Fig. 8 A United Fruit Company official looks over the harvested bananas to see which are fit for market in Honduras. 1954. NPR, There Will Be Bananas, Throughline.

https://www.npr.org/2020/01/07/794302086/there-will-be-bananas