Introduction

The role of public architecture serving as a channel for filtering nineteenth-century French ideals is explored in the town hall of Annaba. Public architecture, such as town halls, schools, or chambers of commerce1, were built as a reflection of colonial strength, consequently resulting in many buildings related to administration expressing the “aesthetic revolution imported by the French to Algeria”2. Although the diffusion of power during the mid 1860s in Algiers allowed “pockets of local power”3 by the indigenous population, it was designed to give the Algerian people only the illusion of independence4.

The French colonization of Algiers took place over three distinct stages: the initial military occupation during the first half of the nineteenth century, settler colonialism, and the period of decolonization culminating in the Algerian Revolution of 1954-19625. During this era, Algiers’ bureaucracy has undergone “constant transformations at the administrative, political, social and economic levels”6. Through different policies from domination to subjugation, the city became a palimpsest, where “traces of history shine through each transformation”7. Urban design and modes of colonial architecture were deployed as tools for subjugation, which served as discursive strategies for administrative power and colonial authority. Hence, the administrative and symbolic power of the town hall of Annaba reflect the transforming colonial policies throughout the nineteenth century, signified by its strategic position within the urban landscape and its neoclassical architectonic elements.

Urban Structure of Annaba

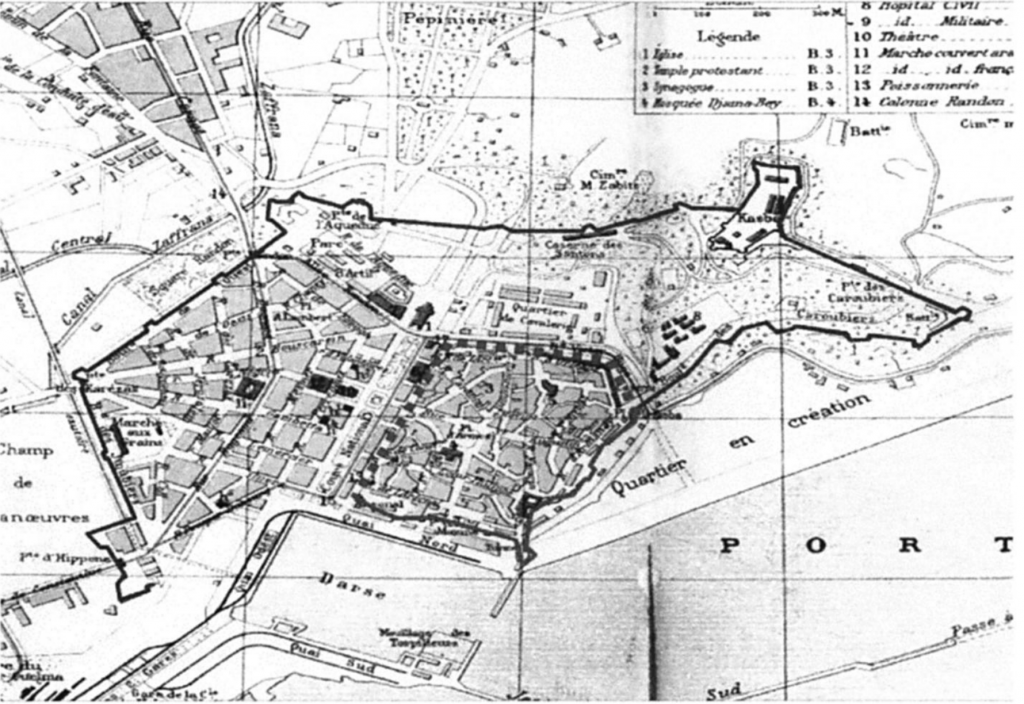

At the urban scale, the French assimilation of Algeria meant “eradicating the existing Algerian socio-physical environment and implanting a new and modern society,” where “parcels of land…a number of buildings…were appropriated, either to be demolished or rehabilitated in accordance with military and administrative functions”8. Annaba, or formerly known as Bône, is a coastal town in eastern Algeria. The town is no exception to the French disruption of Algeria’s socio-urban landscape, where its urban tissue is clearly delineated by two zones; “the organic [on the right] represents the old town and the other geometric or axial [on the left] symbolizes the French colonial urban structure”9 (Fig 2). The town hall is strategically located at the intersection of these two fabrics, symbolizing its ability to connect and govern both sides, simultaneously implying that “the Algerian society was incapable of self-sovereignty”10.

The town hall is located on a trapezoidal piece of land, near the “Revolution Square” (450 E.H–1058 E.C) with a garden in front that conforms to market places, thereby adapting the design of Middle Ages squares to new contexts11. This principle of urban design (a square connecting long axes to give a sense of space and openness12) developed in France during the eighteenth century, where it is also echoed elsewhere in French Algeria, such as the Place du Gouvernement (Fig. 3). However, the organic tangled form of Algiers being shaped by centuries of Islamic life had “prioritized introverted, domestic life,” where homes are turned inward and open around an interior courtyard13. These disruptive modifications drove the local population away as they felt their privacy had been violated, inevitably making more room for European arrivals14. Hence, the town hall as a central monument that disregarded local cultures and patterns of life became a potent symbol of colonial power.

Architectonic Elements as Signifiers of Colonial Policy

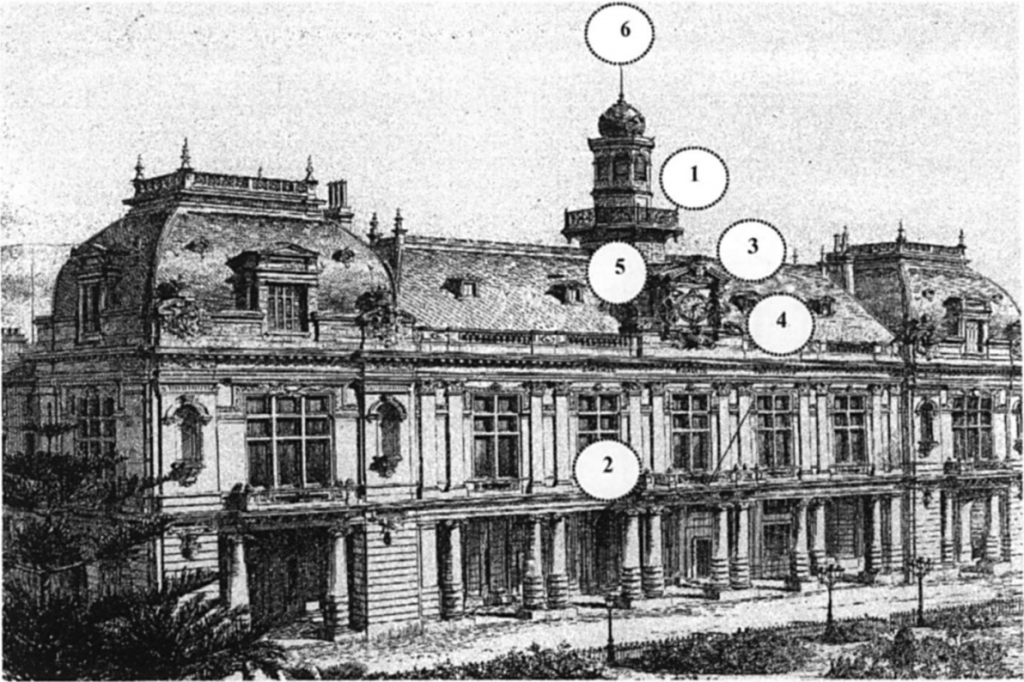

The town hall of Annaba was initially erected around the 1880s15 under a style similar to buildings in northern France, specifically of neo-Greek and neo-Renaissance characteristics that reflected the Second Empire16. This is the period of direct colonial rule in Algeria from 1830 to 1870, where the military regime exerted control over bureaucratic institutions and administrative affairs17.

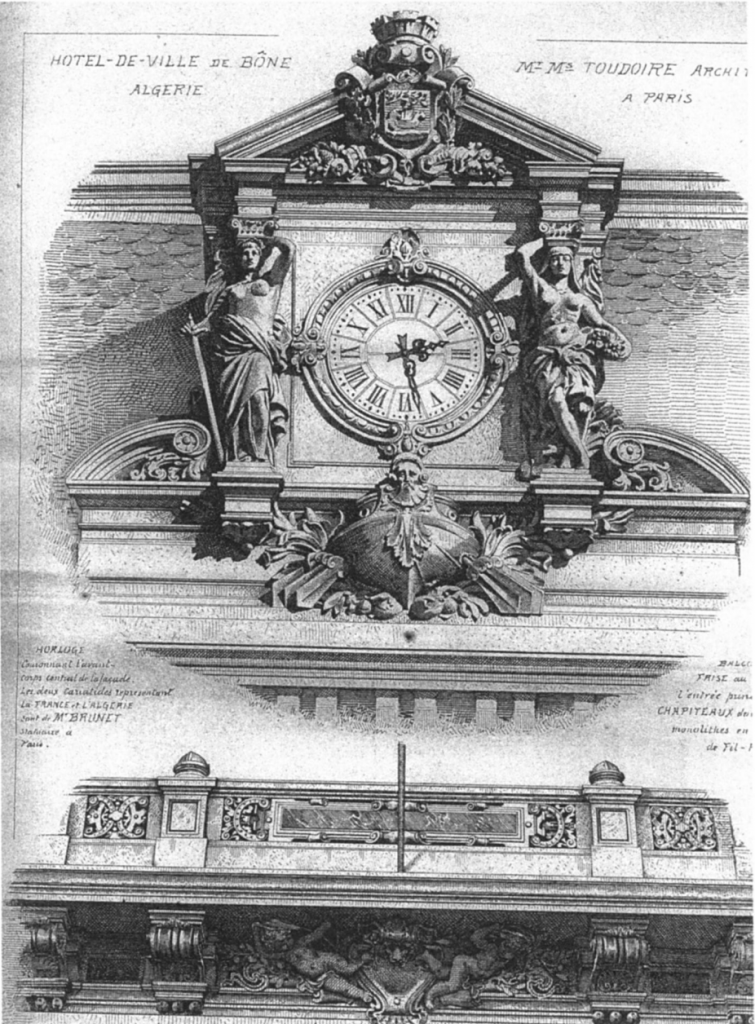

There are five elements of typical town halls in France are identified by Loyer (1987), Gaudet (1929), Narjoux (1870), Viollet Le Duc (1856), and Gloc-Dechezlepretre (2001) to being: The Belfry, the balcony, the clock, the maxim, the armorial bearings, and the arrow18 (Fig. 4). These elements bear commonality in that they all intervene on some level of communal life, as Laure Delrue claims “municipal architecture is an instrument of power”19. For instance, the square-based belfry tower calls citizens together as a sign to the bourgeois that popular assemblies would occur. The clock is an essential composition of the belfry, where the control of time is a measure of power. While the balcony originated as a defensive element in fifteenth century Europe, it took on a decorative function and became a symbol of the oral expression of power towards the people. The armorial bearings, maxim, and arrows are signs displayed to ensure the continuity of European tradition20. Although many of these elements have discontinued their original functions and may seem ornamental, they are inherently coded with colonial meaning that reinforces the power imbalance between the colonizers and the colonized.

By the mid 1860s, the violent transformation of Algiers slowed down as the initial military outpost turned into a permanent French settlement, beginning the settler stage of colonialism. Opposition to the assimilation strategies previously employed arose among members of the colonial administration due to potential economic conflicts, leading the French administration to transition into policies of association instead. In theory, it was based on “cooperation between colonized and colonizer, on working within the framework of native institutions”21. Yet, this method of diffused control is what Foucault describes as the substitution of “a power that insidiously objectifies those on whom it is applied…to…a body of knowledge about these individuals rather than deploy the ostentatious signs of sovereignty”22.

This policy is reflected through the municipal council of Annaba on March 31st, 1883, when they decided to construct their town hall “with an appearance reminiscent of the Metropolis while respecting the local cultural context”23. There were considerations given to the adaptation of local climatic requirements, such as raising the entablature galleries of the edifice to provide more fresh air. Muslim art also inspired the style of the Moorish room, another facet of French architecture adopting to local contexts of climatic conditions24. Other elements such as the encrusted armorial bearing and maxims recall the entangled history of France and Algiers (Fig. 5). As for the pediment, it is supported by two high caryatids that respectively represent Algiers and France. Yet, the middle figurine representing Poseidon is a reference to colonial strength by means of Annaba’s invasion, where swords replace the original paddles on the ship.

The visual expression of architecture and urbanism in French Algiers were the most “accessible signs of the French policy,” where the diffused power is toned down through intermediaries of the “rhetoric of protection, cooperation and preservation, based solidly on the…fundamental difference between the West and the rest of the world”25. The role that the town hall of Annaba plays is twofold: its typological reading is explicitly the production of French culture, but combined with appropriated elements of Algerian culture, it created a new mode of association under the guise of a liberating policy26.

Despite the numerous elements of the town hall, they are not a random sum of parts but can be regarded as constituents of invented traditions meant to serve both the French and the Algerians. Nearing the end of the Algerian Revolution, the belfry tower of the town hall burned down in the fire of June 21st, 1962. Perhaps symbolically, the belfry, “whose aim is to claim the autonomy and power of the city and to stress its space”27 was destroyed. The transformation of Algeria from a highly contested colonial space into an independent landscape continues to undergo change and reclamation in the decades afterwards, where the appearance and meaning of place, the power of place to shape behaviour and customs of the people reflected in its urban design and architecture continue to hold real and symbolic power.

Notes:

1 Khelifa-Rouaissia, Sihem, and Heddya Boulkroune. “The Architecture of the Town Halls of the French Colonial Period in Algeria: The First Half of Nineteenth Century.” p. 421

2 Ibid.

3 Prochaska, David. “Making Algeria French and Unmaking French Algeria.” p.299

4 Hamadeh, Shirine. “Creating the Traditional City: A French Project.” p. 246

5 Prochaska, David. “Making Algeria” p. 300

6 Hadjri, K., & Osmani, M. “The spatial development and urban transformation of colonial and postcolonial Algiers” p. 1

7 Grabar, Henry S. “Reclaiming the City: Changing Urban Meaning in Algiers after 1962.” p. 391

8 Prochaska, David. “Making Algeria” p. 244

9 Khelifa-Rouaissia, “The Architecture of the Town Halls” p. 422

10 Hamadeh, Shirine. “Creating the Traditional City: A French Project.” p. 245

11 Khelifa-Rouaissia, “The Architecture of the Town Halls” p. 462

12 Hadjri, K., & Osmani, M. “The spatial development” p. 4

13 Grabar, Henry S. “Reclaiming the City” p. 392

14 Hadjri, K., & Osmani, M. “The spatial development” p. 4

15 Cannot find historic record of which year it was exactly built, only the dates of when the municipal council were discussing its construction.

16 Oulebsir, N. Heritage uses: Monuments, Museums and Colonial Policies in Algeria (1830-1930)

17 Prochaska, David. “Making Algeria” p. 300

18 Khelifa-Rouaissia, “The Architecture of the Town Halls” p. 423

19 Ibid. p. 424

20 Ibid.

21 Hamadeh, Shirine. “Creating the Traditional City: A French Project.” p. 246

22 Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison.

23 Khelifa-Rouaissia, “The Architecture of the Town Halls” p. 246

24 Ibid.

25 Hamadeh, Shirine. “Creating the Traditional City: A French Project.” p. 247

26 Ibid.

27 Khelifa-Rouaissia, “The Architecture of the Town Halls” p. 246

Bibliography

Barclay, Fiona, Charlotte Ann Chopin, and Martin Evans. “Introduction: Settler Colonialism and French Algeria.” Settler Colonial Studies 8, no. 2 (2017): 115–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473x.2016.1273862.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. (1979) Vintage Books, New York.

Grabar, Henry S. “Reclaiming the City: Changing Urban Meaning in Algiers after 1962.” Cultural Geographies 21, no. 3 (2013): 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474013506361.

Hadjri, K., & Osmani, M. “The spatial development and urban transformation of colonial and postcolonial Algiers” In Y. Elsheshtawy (Ed.), Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope in a Globalizing World (2004): 29–55. London, UK, Routledge

Hamadeh, Shirine. “Creating the Traditional City: A French Project.” Forms of Dominance: On the Architecture and Urbanism of the Colonial Enterprise. (1992): 241-259. Avebury

Khelifa-Rouaissia, Sihem, and Heddya Boulkroune. “The Architecture of the Town Halls of the French Colonial Period in Algeria: The First Half of Nineteenth Century.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21, no. 2 (2016): 420–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0352-7.

Oulebsir, N. Heritage uses: Monuments, Museums and Colonial Policies in Algeria (1830-1930). (2004) House of Human

Prochaska, David. “Making Algeria French and Unmaking French Algeria.” Twenty Years of theJournal of Historical Sociology, n.d., 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444309720.ch13.

Photo Sources

Figure 1 – Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies (TALIM), Paul Servant (photographer), ca. 1910-1930

Figures 2, 4, 5 – Khelifa-Rouaissia, Sihem, and Heddya Boulkroune. “The Architecture of the Town Halls of the French Colonial Period in Algeria: The First Half of Nineteenth Century.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21, no. 2 (2016): 420–32.

Figure 3 – M. Osmani, 2003