The Elmina Castle in Ghana was the first European fortress built in the tropics in 1482, it was originally built for trade and missionary work by the Portuguese.1 The castle was an important node in the transatlantic slave trade along with several other fortresses and trading posts built along the West African coast.2 By examining the division and inhabitation of space through the ideas of gender and race at the Elmina Castle the building design could be further understood. It is also important to look at how these ideas dictated accessibility and restriction of parts of the building. Along with this looking at the choreography of movement of particular occupants and how that influenced the creation of the architecture. The complexity and multiplicity of dualities at play looking at male and female, free and enslaved and European and African informed how the project operated. This helps to show why the project has been of interest to scholars, locals and foreigners alike. The Elmina Castle has been a pertinent artifact of slave trade architecture for centuries and it will likely be relevant for many centuries to come.3

The hierarchy of spaces at the Elmina Castle is crucial to understanding the organization of the building. The large scale of the project allowed it to operate as a small town within its walls.4 Within the building the greater importance that a individual was thought to have the higher up in the building that they would have lived.5 At the very top of the building was the living quarters of the governor. The governor was the official in charge of the castle and this residence had optimal views for surveillance of the inner castle activity.6 Immediately below that was the deputy governor’s quarters and underneath the deputy governors’ quarters were the quarters for the traders, pastors and the soldiers.7 When under the Portuguese rule there was a church and administrative center facing each other and opposite ends of the courtyard.8 In 1613 the castle was taken over by the Dutch, they rebuilt parts of the castle and expanded it to become a slave collection and trading point.9 The former Portuguese church in particular became a slave trading point on the bottom floor and a soldier meeting space on the top.10 As well the store rooms that we the Portuguese used for storage were converted to dungeons for the enslaved Africans.11

The advantage to keeping the enslaved underground was good security and since there were very few entrances, these entrances could be closely monitored by the garrison to protect against any insurrection.12 There were separate dungeons for male and females each of which had very little natural light and ventilation.13 The dungeons for enslaved men were the darkest and most cavernous spaces in the building.14 The size of the male dungeons in relation to the smaller female dungeons helped to reflect the ratio of males to females that were shipped away to work on plantations.15 In both cases there wasn’t adequate space to bathe and to clean oneself.16 As well these dungeons emitted the stench of human excrement, bodily fluids and death.17 Often times the slaves had to dwell in their own feces as they were tightly packed together.18 When the Europeans were to open the entrance to the dungeons certain mornings the stench could spread over the entire fortress.19 It is supposed that 600 men and 400 females were in the slave dungeons at one time.20 Within the building a space that was of particular importance was the main courtyard that was able to serve many functions.21 Some of the spaces that could be accessed from this courtyard were the condemned cell and the solider cell.22 The solider cell was for drunken soldiers who misbehaved, and they would be put in the cell as punishment. 23 Though the condemned cell was for the slaves who would resist or would fight for freedom, they were kept in the cell without any food and any water and they were left to die.24 There would be particular instances where dead or decomposing slaves would be placed with slaves who were alive, and this was used as deterrent for those in the dungeons in order for them to behave.25Another important use of the key use of the courtyard was in preparation for the slave sales when ships would arrive at the castle.26For this preparation castle slaves would wash and oil the bodies of the Africans to be sold.27 This event took place in the courtyard with the slaves either chained or loose so that they would form a circle.28After that the buyer would examine the teeth, eyes and body of the slave.29 The slave would have to perform several movements with their arms and legs and would also have their private parts examined as well.30 Slaves that were selected for sale were physically marked as human property branded like livestock.31

By looking at the Elmina Castle the hierarchy of space set up an interesting relationship between race and space. In this relationship where the occupants’ race would not only determine what parts of the castle that they would inhabit it would also dictate the amount of space they would have to bathe, to sleep and their proximity to other bodies.32 These aspects along with others such as natural lighting and ventilation which are all drastically different for occupants of the castle based upon race and enslavement.33

Choreography of Movement by the Female Slaves of the Elmina Castle

A key aspect of the spatial organization of the Elmina Castle was that it facilitated the exploitation and abuse of the female slaves. There were 400 female slaves in the dungeon at a time and their presence was important because many Europeans did not bring their wives to West Africa.34 The governors, traders and soldiers were all male and they would deliberately sexually abuse the female slaves from the dungeons.35 Spatially the governor’s quarters were in close proximity to the female dungeons.36 The governor was able to stand on his balcony and order female slaves from the dungeons into a small courtyard and from there he would make his choice.37 If a female was chosen it was up to the soldiers to clean her and to do so they brought water from the cistern and they washed the woman in the courtyard, after that she would then be given something to eat.38 When that was complete, she would have to go up a narrow flight of stairs to the governor’s bedroom.39 This choreography of movement for the female slaves was important because it gave a spatial sequence to the exploitation of the females in the castle and this sequence from the dungeon to the courtyard up the small staircase to the governor’s bedroom was undertaken frequently by countless enslaved women.40 This helps to show the relationship between the enslaved African females and the European castle occupants. This abuse of female slaves could also be seen in Jefferson’s Monticello centuries later.41 At Monticello there was narrow private stairway from the slave quarters to Jefferson’s bedroom that he would use to exploit female slaves.42 The occupant behaviors’ and choreography of movement seen at the Elmina Castle helps to foreshadow the activities at slave plantations like Jefferson’s Monticello centuries later.43

Conclusion

The Elmina Castle was a crucial node in the transatlantic slave trade for centuries after its inception.44 By analyzing the division and inhabitation of space through the ideas of gender and race the building design of the castle could be further understood. It is also important to look at how these ideas dictated accessibility and restriction of parts of the building. This restriction presented itself looking at how the slaves were relegated to the dungeons underground and the Europeans were housed in the upper levels.45 As well the choreography of movement of the female slaves as they were only allowed to access the upper levels when they were being exploited and abused by the European males. This complexity and multiplicity of dualities at play looking at male and female, free and enslaved, European and African informed how the castle operated. In the contemporary time the Elmina Castle still contains valuable information to be observed, recorded and disseminated for generations to come.

Notes

1Carl Anthony. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters: Part I, Prelude to New World Architecture.” (Landscape 20, no. 3, 1976), 14.

2Carl Anthony. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters: Part I, Prelude to New World Architecture.”, 14.

3Ibid.

4Cheryl, Finley “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles: The Former Sites of the Slave Trade on the Ghanaian Coast” in and D. Medina Lasansky, eds. Architecture and Tourism: Perception, Performance and Place (Berg, 2004), 110.

5Cheryl, Finley “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles: The Former Sites of the Slave Trade on the Ghanaian Coast”, 110.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.

8Jordan Coleman A. “Rhizomorphics of Race and Space: Ghana’s Slave Castles and the Roots of African Diaspora Identity.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 60, no. 4 (2007): 50-51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40480850.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

11Ibid.

12Louis P. Nelson. “Architectures of West African Enslavement.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 21, no. 1 (2014): 108-109 doi:10.5749/buildland.21.1.0088.

13Cheryl, Finley “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles,” 110.

14Ibid.

15Ibid.

16Ibid.

17Ibid.

18Ibid.

19Ibid.

20Peter Kwame Womber. “From Anomansa to Elmina: The Establishment and the use of the Elmina Castle – from the Portuguese to the British.” Athens Journal of History 6 no.4 (October 2020): 356-358. doi:10.30958/ajhis.6-4-4.

21Womber. “From Anomansa to Elmina,” 356.

22Finley “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles,” 110.

23 Edward M. Bruner “Tourism in Ghana: The Representation of Slavery and the Return of the Black Diaspora.” American Anthropologist, New Series, 98, no. 2 (1996): 295. http://www.jstor.org/stable/682888.

24Edward M. Bruner “Tourism in Ghana,”295.

25Ibid.

26Louis P. Nelson. “Architectures of West African Enslavement,” 108.

27Ibid.

28Ibid.

29Ibid.

30Ibid.

31Ibid.

32Ibid.

33Ibid.

34Finley “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles,” 116.

35Ibid.

36Ibid.

37Ibid.

38Ibid.

39Ibid.

40Carl Anthony. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters: Part I, Prelude to New World Architecture.”, 14.

41Ibid.

42Ibid.

43Ibid.

44Ibid.

45Finley “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles,” 116.

Images

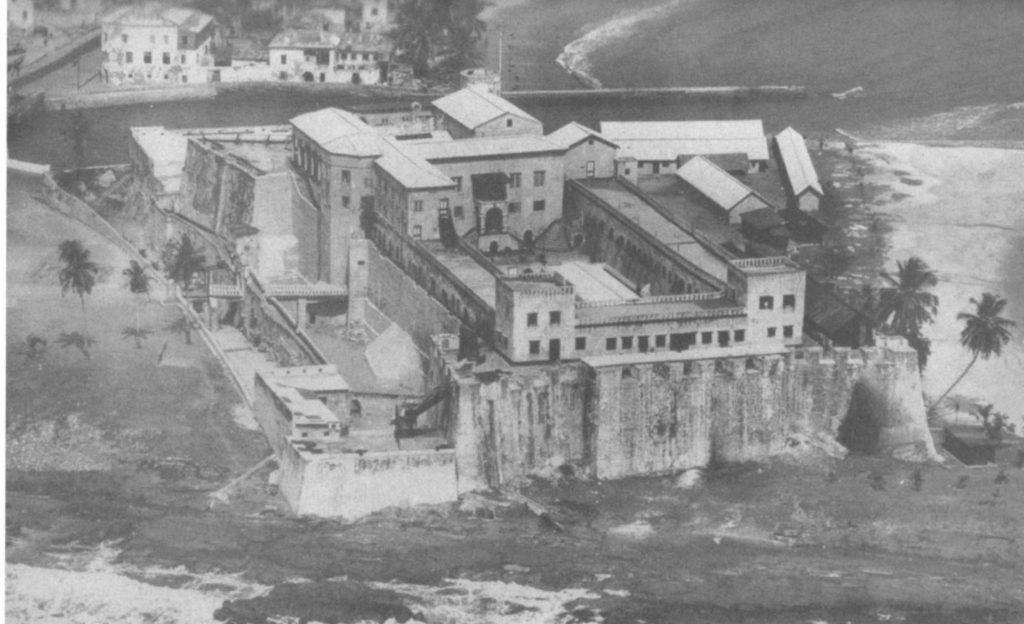

Figure 1: A.W. Lawrence. Aerial Perspective of Elmina Castle.1964, Trade Castles and Forts of West Africa (Stanford University Press) Accessed February 16, 2021.

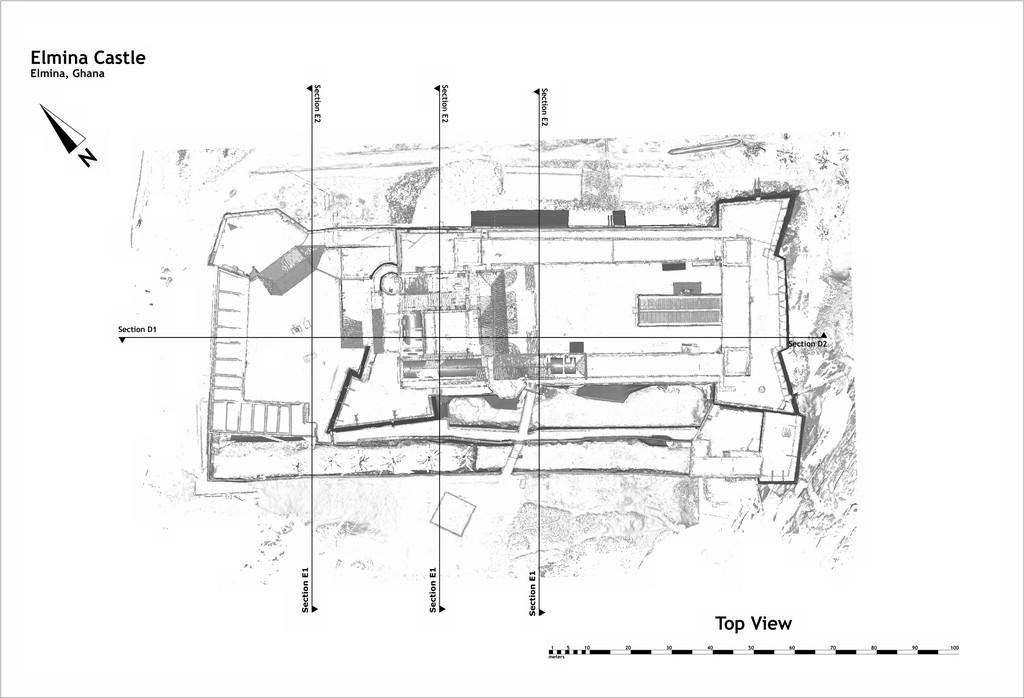

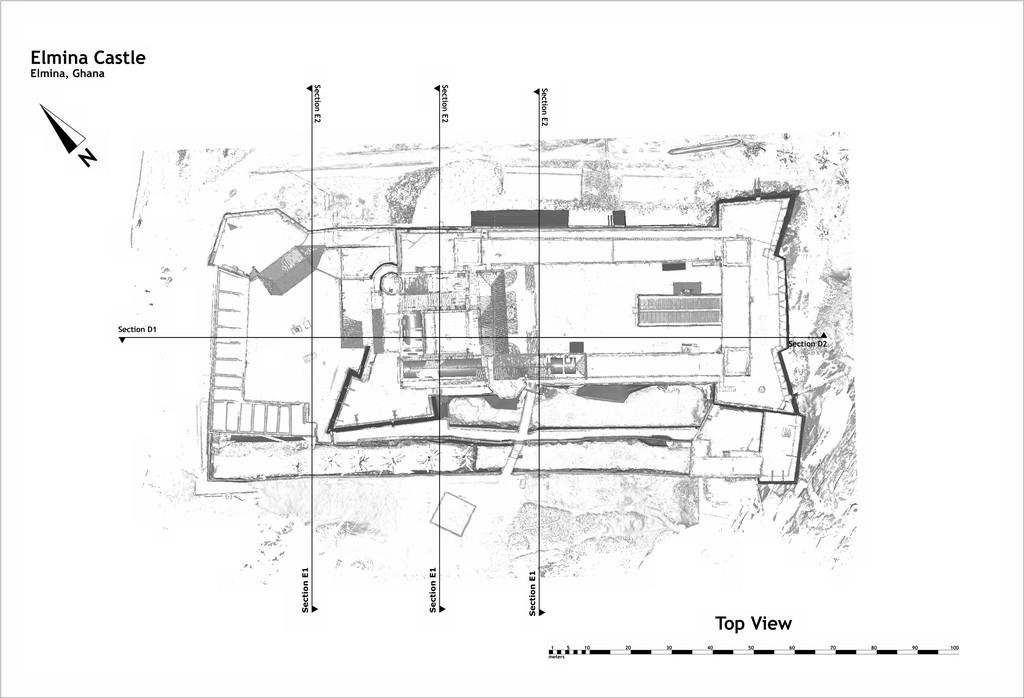

Figure 2: Ruther, Heinz, Held, Christoph, Neeser, Rudolph, and Schroeder, Ralph. Top View of Elmina Castle, Ghana. 2006. Accessed February 16, 2021. doi:10.2307/al.ch.document.uctnew0002483.

Figure 3: Ruther, Heinz, Held, Christoph, Neeser, Rudolph, and Schroeder, Ralph. Condemned Cell Image, Ghana. 2006. Accessed February 16, 2021. doi:10.2307/al.ch.document.uctnew0000552.

Figure 4: Ruther, Heinz, Held, Christoph, Neeser, Rudolph, and Schroeder, Ralph. Main Courtyard Image, Ghana. 2006. Accessed February 16, 2021. doi:10.2307/al.ch.document.uctnew0001148.

Figure 5: Ruther, Heinz, Held, Christoph, Neeser, Rudolph, and Schroeder, Ralph. Governor’s Balcony Image, Ghana. 2006. Accessed February 18, 2021. doi:10.2307/al.ch.document.uctnew0001804.

Bibliography

Anthony, Carl. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters: Part I, Prelude to New World Architecture.” Landscape 20, no. 3, 8-19, 1976.

Bruner, Edward M. “Tourism in Ghana: The Representation of Slavery and the Return of the Black Diaspora.” American Anthropologist, New Series, 98, no. 2 (1996): 290-304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/682888.

Coleman A, Jordan. “Rhizomorphics of Race and Space: Ghana’s Slave Castles and the Roots of African Diaspora Identity.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 60, no. 4 (2007): 48-59.http://www.jstor.org/stable/40480850.

Finley, Cheryl “Authenticating Dungeons, Whitewashing Castles: The Former Sites of the Slave Trade on the Ghanaian Coast” in and D. Medina Lasansky, eds. Architecture and Tourism: Perception, Performance and Place ,109-126. Berg, 2004.

Kabir, Ananya Jahanara . “Elmina as Postcolonial Space”, Interventions, 22:8 (2020), 994-1012, DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2020.1753555

Kwame Womber, Peter. 08/2020. “From Anomansa to Elmina: The Establishment and the use of the Elmina Castle – from the Portuguese to the British.” Athens Journal of History 6 (4): 349-372. doi:10.30958/ajhis.6-4-4.

Nelson, P. Louis. “Architectures of West African Enslavement.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 21, no. 1 (2014): 88-125. doi:10.5749/buildland.21.1.0088.

One reply on “Elmina Castle 1482: Division of Race and Hierarchy of Space”

Nice work ????????????