Introduction

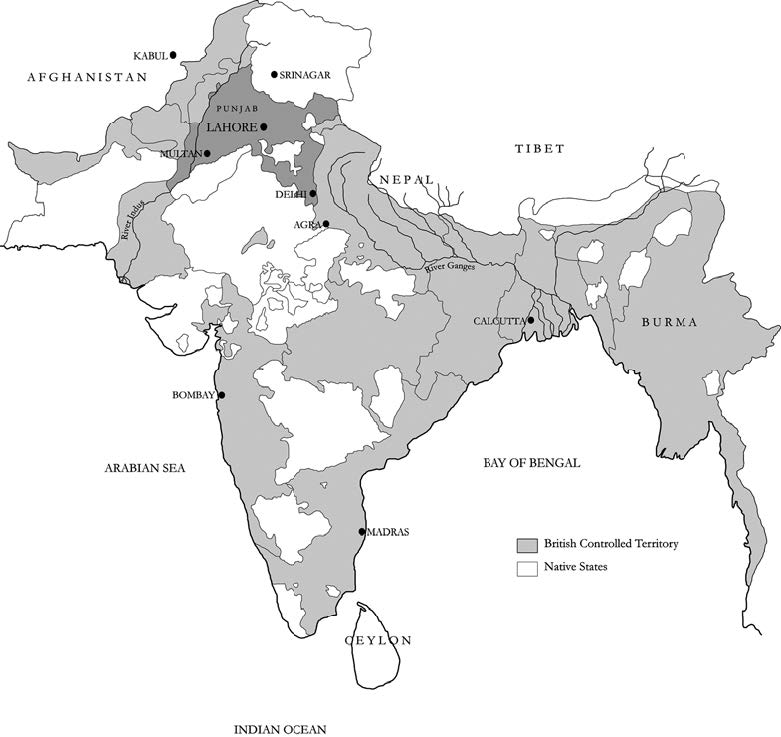

By the end of the 19th century, it is estimated that close to 150 million pounds-sterling was invested by British companies in the Indian railway system; the single greatest investment in the British Empire.[1] By 1947, the end of the British Raj, 57,000 miles of track had been laid down in Colonial India, 225,000 freight cars amassed, and 26-billion-ton miles of freight carried.[2] The railway networks were essential to Imperial Britain, supplying British industry with substantial imports of raw materials, a forced customer of British manufactured products, and the military security against internal and foreign threats. Unsurprisingly, the railways also had the effect of transforming the urban fabric of India, shaping the growth of crucial port cities, such as Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, where railway terminals were eventually built.

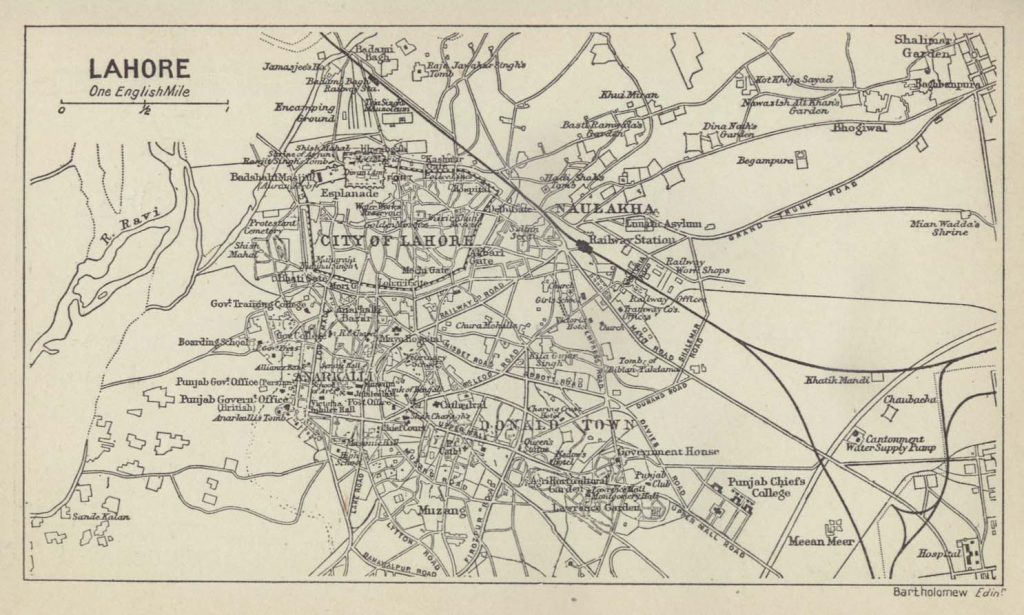

Lahore, in contrast, based deep within the subcontinent’s interior was already a prominent city long before British rule. Located in the Punjab province and present-day Pakistan, Lahore was the political and commercial capital of the Mughal Empire from the 16th to 18th century, and the Sikh Empire from 1801-1849, before the region was annexed to British India in 1849 after two Anglo-Sikh wars.[3] The agriculturally rich plains surrounding the city made Lahore a key target for railway development and colonial intervention.[4] However, British rule was met with consistent and widespread resistance in the culturally and historically diverse districts of the Old Walled City.[5] Combined with the violent Indian Rebellion of 1857, the siting and design of the eventual railway station at Lahore was greatly influenced by concerns for security and the urgent need to project imperial strength.

‘Making Lahore Modern’ by William J. Glover documents the urban transformation of Lahore under British rule, investigating the traditions and actors that came to organize the material fabric of the city. In his book, Glover quotes David Scott’s description of colonial governmentality as “concerned above all with disabling old forms of life by systematically breaking down their conditions, and with constructing in their place new conditions so as to enable—indeed, so as to oblige—new forms of life […]“.[6] Glover argues that the British exerted their colonial power through the built environment, rebuilding the material conditions that enabled “old forms of life” and gradually reshaping society in Lahore without the “need for more forceful approaches”. [7] The Lahore Railway Station, completed in 1861, can thus be understood not only through the economic, strategic, and administrative functions it served the British Empire, but also by the architectural expressions of authority, control, and legitimacy that helped secure their rule in Lahore.

Economic Function & Expression of Authority

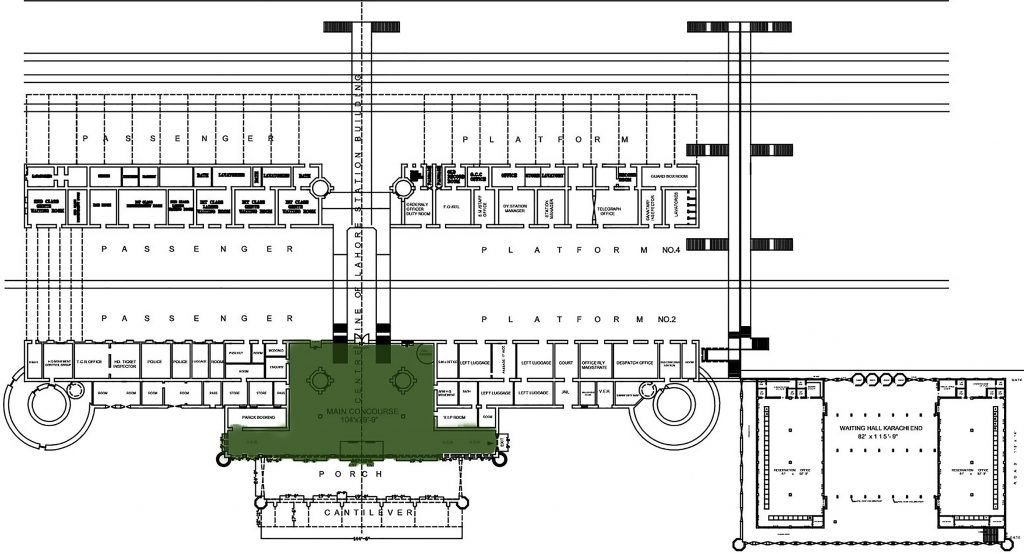

In 1855, a railway line in Northern India was proposed, linking Lahore with the major port city of Karachi.[8] The Punjab region was a highly fertile agricultural zone that not only produced tobacco and indigo, by supplied cotton, wool, and salt as well.[9] Connecting all the major towns within the highly productive Punjab province to the seaport was thus essential to unlocking the opulent store of raw materials for export. The railway station at Lahore was designed by civil engineer William Brunton and approved for construction by the Scinde Railway Company on July 15th, 1857.[10]

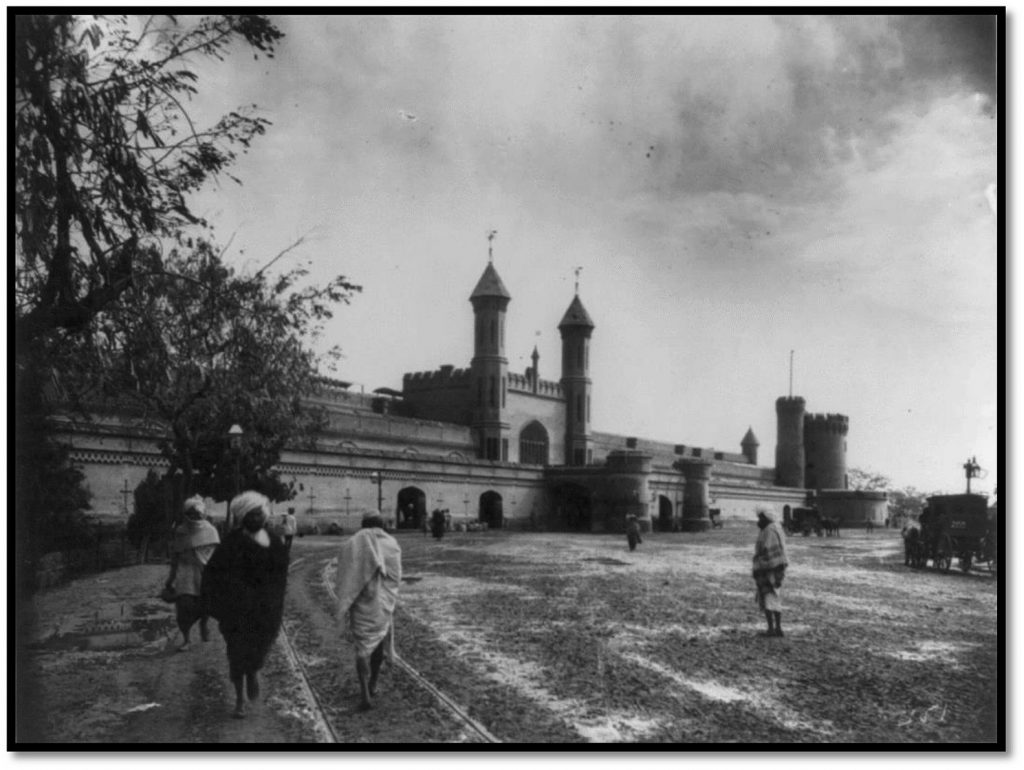

Brunton sited the railway station in the suburbs of Lahore, 400 yards east of the Old Walled City constructed during the Mughal Empire, and atop the ruins of the old Sikh Cantonment of Naulakha.[11] Besides being a safe distance away from the flood zone of the River Ravi, the decision to build the railway station near the provincial center of the two previously conquered empires was no mistake. Railways were a symbol of progress and technological achievement in Victorian England.[12] However, in colonial India, the railway symbolized Britain’s vehicle of colonial domination and imperial authority. What better site to impose this symbol of power than atop the spoils of British military victory? Mosques and tombs from the Mughal and Sikh empires were either repurposed or demolished for the construction of the station, “asserting the authority to rule by physically appropriating (and sometimes destroying) a previous ruler’s buildings.[13]

By physically dismantling the significance of the city’s past and ushering in a new symbol of power in its place, the British constructed a new way of life through the built environment that served imperial interests first and foremost. For example, railway companies charged reduced rates on the carriage of bulk goods for export to Britain, as well as British imports to the Indian interior.[14] The interlocking of the British and Indian economies awarded Britain with a trade surplus with India, while deepening India’s economic dependence on Britain. As a result, millions of artisans in villages and towns throughout India that could no longer compete with the import of British manufactured products and had no choice but to assimilate into the new colonial way of life.[15]

Strategic Function & Expression of Control

Despite receiving approval in 1857, construction of Lahore Railway Station did not begin for another two years. The project was delayed by the May 10th, 1857 Indian Rebellion that erupted in Northern India. The uprising against the British East India Company began as a mutiny by locally employed sepoys in the cantonment of Meerut, 270 miles southeast of Lahore.[16] This revolt triggered further unrest and violence throughout central India and the upper Ganges plain, with many rebels occupying British quarters and attacking British civilians.[17] After a year of conflict and war, control of central India was re-established by the British Army in June 1858.[18] However, British rule in India was for the first time under serious threat.

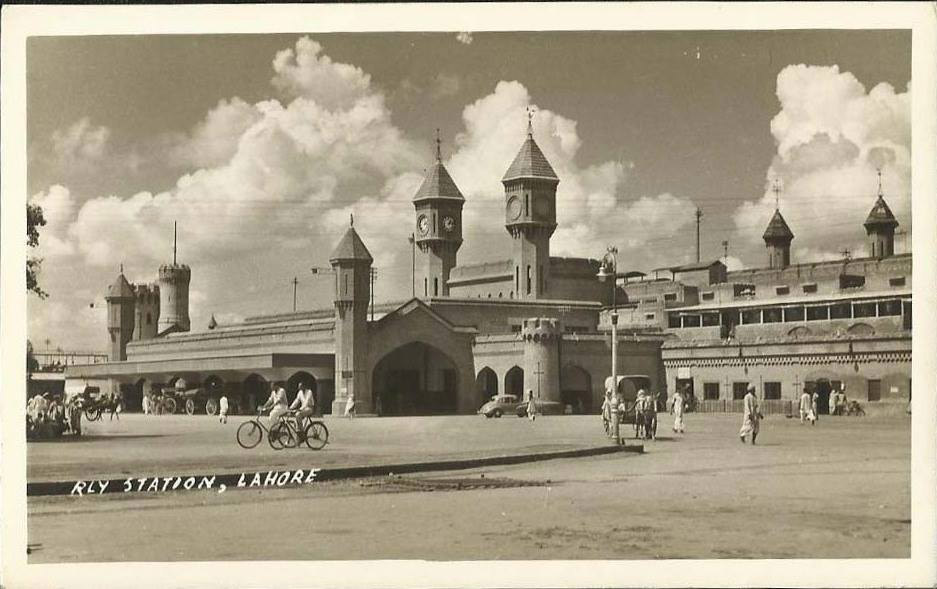

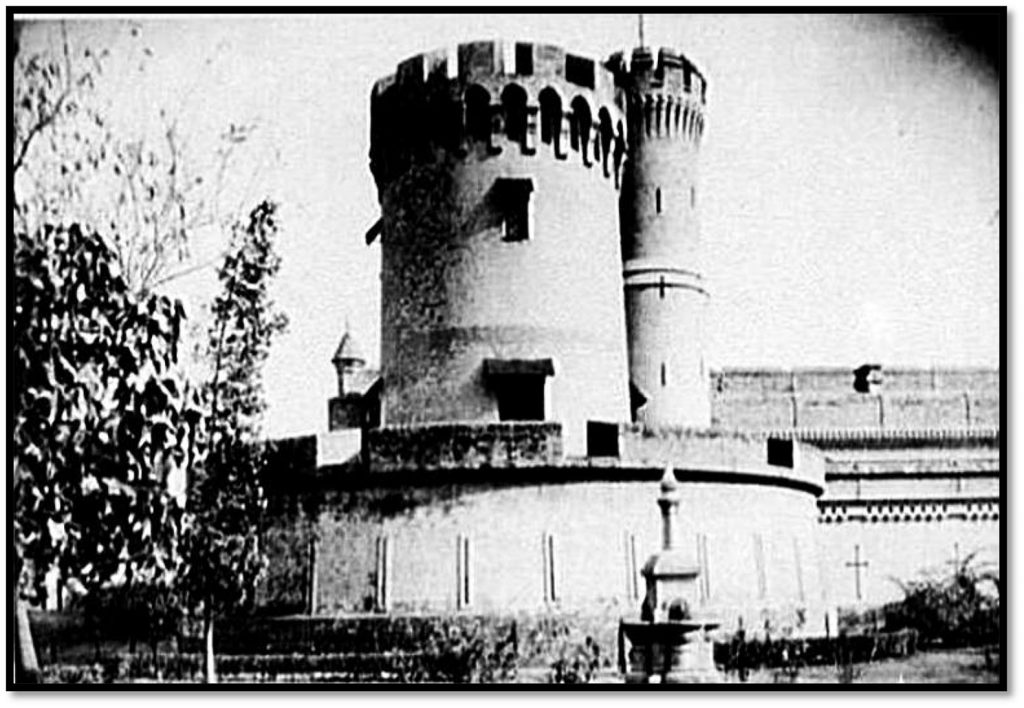

As construction of the Lahore railway station resumed in 1859, its final design reflects the fear of a future rebellion and an attempt to reassert control in the region. Documenting the urban history of Lahore in 1892, author Syad Muhammad Latif describes the railway station as resembling, in appearance, “[…] one of the forts of the country, and is, in fact, a fortified position, provided with the means of defense in case of emergency“.[19] Like a fortified medieval castle, the two rectangular blocks that house the station facilities are protected by thick walls populated with projected turrets and bomb-proof towers toped with crenellations.[20] Each turret is complete with loopholes for 360° view of the surrounding city and directing rifle fire along the building’s main approaches.[21] To secure the station against attack and provide refuge for British civilians, two heavy iron gates were installed at the entrances and exits of the train sheds that could seal off the rest of the city forming a fortified bunker.[22]

Following the 1857 Rebellion, the security of British citizens and its infrastructure become the Empire’s primary concern. Significant financial investments were directed away from civil projects towards military expenditures and the fortification of the railway network, the key to Britain’s colonial rule in India.[23] The castle-like design of Lahore Railway Station is a testament to this imperial obsession, which is in stark contrast to the extravagant and proud Victoria Terminus in Bombay built in 1887, several decades after the rebellion.[24] Despite the characterization of Lahore railway station as a defensive citadel in the literature, I would argue that its design had the opposite effect of projecting strength, control, and dominance. Siting this fortified bulk 400 yards from the city center sends an imposing message of surveillance and acts as a physical deterrent against future revolts, much like Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon. Similarly, the fortification of a railway station ensures that British troops can be rapidly and securely deployed should another revolt erupt in the city. The design of the station in a sense pacified the surrounding population and exerted pre-emptive control over the city.

Administrative Function & Expression of Legitimacy

The Lahore railway station was completed in 1861 by Mian Mohommad Sultan Chughtai, a contractor with the Public Works Department of Lahore.[25] The station officially opened on March 1, 1862.[26] Interestingly, the building combines both classic European and Islamic architectural elements, an amalgamated style known as ‘Indo-Saracenic‘ architecture.[27] Drawing from the Mughal and Sikh heritage of the Punjab region, the British appropriated Islamic design elements for decoration on the exterior of the building, while planning the interior according to British design standards.[28]

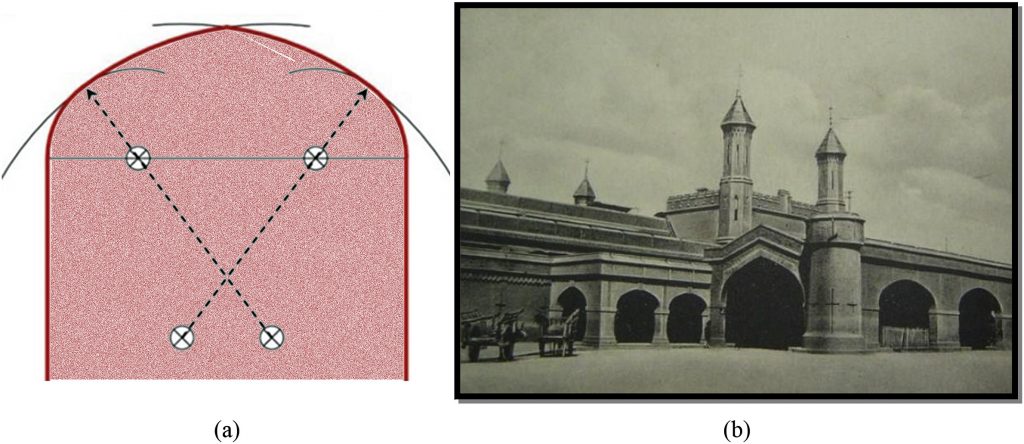

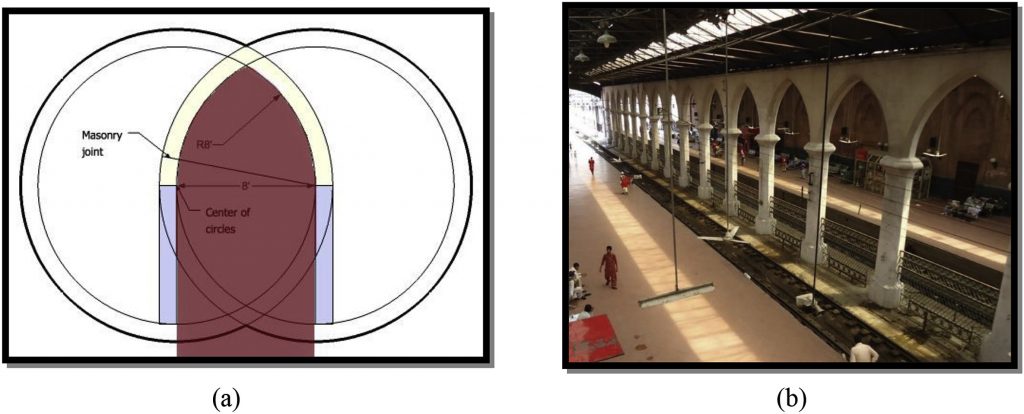

An example of this fusion is the use of Tudor arches on the building’s exterior and the use of Gothic arches inside the station. Tudor arches, an important architectural feature of the Mughal empire, is characterized by it four-centered arch that terminates at a distinct apex and its tendency for the arch to be wider than it is tall.[29] Tudor arches were used primarily at the station entrances (on either side of the entry portico), and as windows on the building’s façade. Gothic arches in comparison, come from a European tradition and are distinguished by its large height two-arc segments that form a sharp point.[30] Rows of gothic arches can be found inside the station’s train shed supporting the longitudinal span and cavernous height of the roof.

Besides adapting to the local climate and building materials, incorporating Islamic architectural features was a conscious decision to “give an illusion of traditional authority and continuity between the Mughal, Sikh, and British empires and so help to validate the latest colonial administration“.[31] Seeking to project themselves as legitimate successors to the Sikh and Mughal empires, the British co-opted traditional design cues that would be more readily accepted by the local and native population.[32] Additionally, the mostly brick masonry building was constructed with both newer bricks and bricks taken from the ruins of the old city.[33] Reusing elements from the older city and incorporating Indo-Saracenic architecture in the railway station served an administrative function in reshaping life in Lahore according to British rule and further cementing their colonial power.

Conclusion

The railway station at Lahore represents an integral node in the Indian Railway network for the British Empire. The station sits at the center of the capital of the Punjab province, linking a highly productive agricultural region with prominent port cities across the subcontinent. However, the station at Lahore is unlike others that were built subsequently. Designed during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the siting and architectural design of the station at Lahore reflect the entangled relationship between the railways and the colonial state, when the later was threatened and at its most vulnerable. The decision to site the station next to the Old Wall City from the Mughal Empire, design an imposing citadel, and appropriate Islamic architectural features expresses the authority, control and legitimacy that was most important to the British Empire in solidifying their rule of colonial India.

Bibliography

Ali, Naubada, and Zhou Qi. “Defensible Citadel: History and Architectural Character of the Lahore Railway Station.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 9 (June 1, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2020.05.003.

Bryant, Julius. “Colonial Architecture in Lahore: J. L. Kipling and the ‘Indo-Saracenic’ Styles.” South Asian Studies 36, no. 1 (January 2, 2020): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2020.1721111.

Chrimes, Michael. “Architectural Dilettantes: Construction Professionals in British India 1600-1910. Part 2. 1860-1910: The Advent of the Professional.” Construction History 31 (January 1, 2016): 99–139.

Din, Naeem. “Shadows of Empire: The Mughal and British Colonial Heritage of Lahore.” Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects, May 1, 2018. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2691.

Glover, William J. Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. NED-New edition. University of Minnesota Press, 2008. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttskzh.

Kerr, Ian J. “Representation and Representations of the Railways of Colonial and Post-Colonial South Asia.” Modern Asian Studies 37, no. 2 (2003): 287–326.

Khan, A., S. Arif, O. Nadeem, and A. Anwer. “British Railway Architectural Legacy in Lahore: History, Importance and Buildings’ Priorities for Conservation.” Pakistan Journal of Science 65, no. 3 (September 2013): 392–98.

Latif, Syad Muhammad. Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities: With an Account of Its Modern Institutions, Inhabitants, Their Trade, Customs, &c. Printed at the New Imperial Press, 1892.

Ovais, Hira. “Architectural Styles during the British Raj in Lahore.” International Journal of Environmental Studies 73, no. 4 (July 3, 2016): 616–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2016.1192407.

Satya, Laxman. “British Imperial Railways in Nineteenth Century South Asia.” Economic and Political Weekly 43 (November 22, 2008): 69–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/40278213.

Thorner, Daniel. “The Pattern of Railway Development in India.” The Journal of Asian Studies 14, no. 2 (February 1955): 201–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2941731.

Notes

[1] Satya, “British Imperial Railways”, 69.

[2] Thorner, “The Pattern of Railway Development in India”, 211.

[3] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, xi-xii.

[4] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, 4.

[5] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, 28.

[6] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, xxii.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Khan et al., “British Railway Architectural Legacy in Lahore”, 392.

[9] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, 4.

[10] Khan et al., “British Railway Architectural Legacy in Lahore”, 392.

[11] Ali and Qi, “Defensible citadel”, 809.

[12] Din, “Shadows of Empire”, 40.

[13] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, 18.

[14] Thorner, “The Pattern of Railway Development in India”, 208.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Chrimes, “Architectural dilettantes”, 100.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Latif, Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities, 286.

[20] Ovais, “Architectural styles during the British Raj in Lahore”, 623.

[21] Glover, Making Lahore Modern, 23.

[22] Ovais, “Architectural styles during the British Raj in Lahore”, 623.

[23] Chrimes, “Architectural dilettantes”, 100.

[24] Kerr, “Representation and Representations”, 291.

[25] Bryant, “Colonial Architecture in Lahore”, 63.

[26] Khan et al., “British Rail Architectural Legacy in Lahore”, 392.

[27] Ovais, “Architectural styles during the British Raj in Lahore”, 617.

[28] Ovais, “Architectural styles during the British Raj in Lahore”, 618.

[29] Ali and Qi, “Defensible citadel”, 813.

[30] Ali and Qi, “Defensible citadel”, 814.

[31] Bryant, “Colonial Architecture in Lahore”, 62.

[32] Ovais, “Architectural styles during the British Raj in Lahore”, 617.

[33] Ali and Qi, “Defensible citadel”, 815.