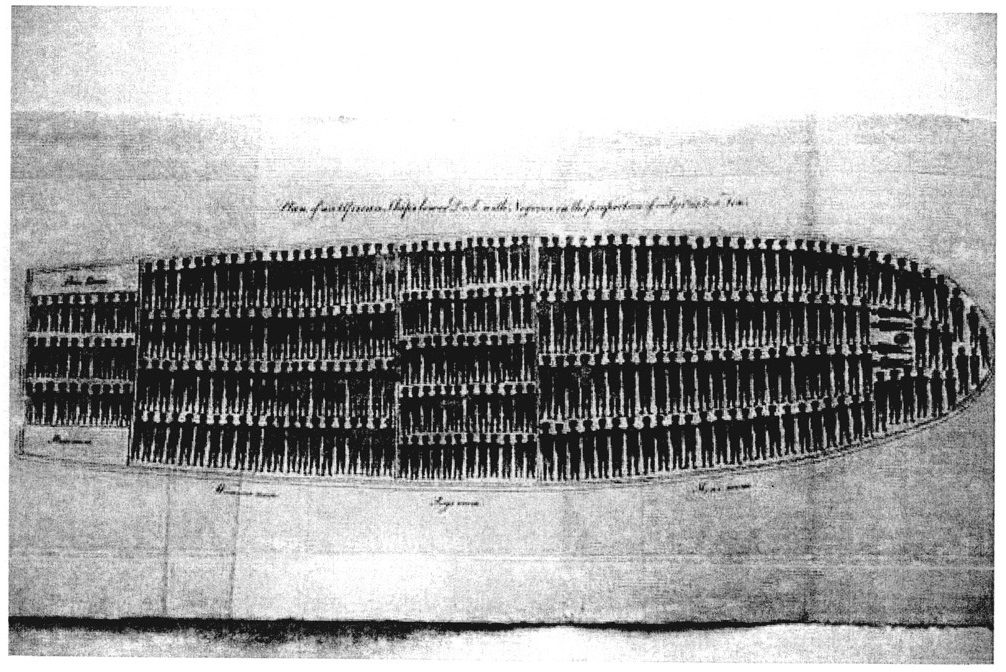

Fig. 1.Plan of an African Ship’s lower deck with Negroes in the Proportion of only one to a Ton, 1789, In Black Art and the Aesthetics of Memory, by Cheryl Finley (Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, 1969)

In 1789, the Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in the proportion of only One to a Ton’ was created. The engraving was the initiative of the Plymouth Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST); and its impact on the trajectory of the slave trade in Britain was the most profound of any visual media(Wood 1997, 212-214). As Wood’s articulates, the ‘Plan’ is a crude representation of the slaver, the Brookes, and only later was its adaptation by the SEAST London Committee into a highly detailed and architecturally rendered image: ‘Description of a Slave Ship’, did the imagery truly take a primary role in political and public discourse in support of abolition (Ibid., 217-218). That is a history of the ‘Description’ that explains how the image was instrumental in the fight for abolition. There is also a parallel and critical history that shows the ‘Description’ to be a strategy that aided in the social processes of subjugation and the creation of the idea of racial difference. Considering the multiple lives of the image locates a point of tension that is productive; namely because it counters the tendency to take socio-spatial representations as neutral cultural artifacts. Instead, this perspective situates the architectural representation of the slaver as a source of the concept of race, and constitutive of the European Enlightenment project, the idea of civilization, and the engines of industrial capitalism and colonialism – that is, the dominant and default way of thinking about the world.

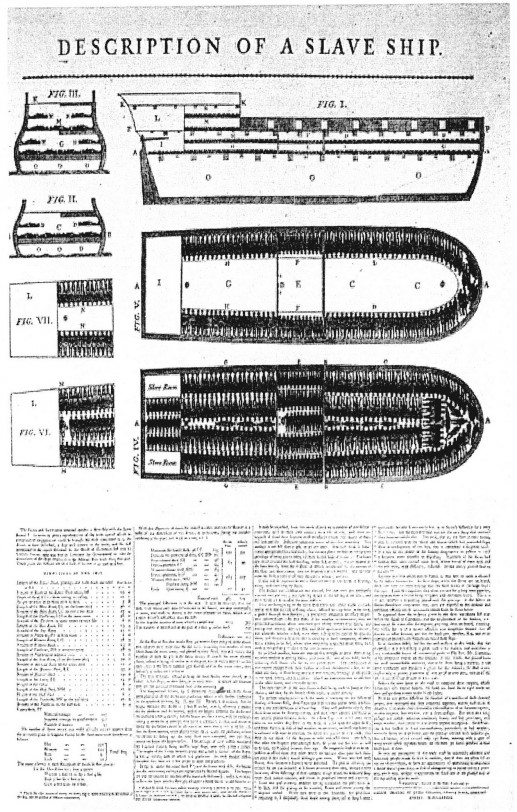

Among the most well-known examples of absolutist propaganda, the schematic of the 18th-century Liverpool-based slave ship, the Brookes, is one of the most shocking and influential (see figure 1). The original engraving was published as a 1700-edition broadside print accompanied with a pamphlet advocating for the end of the slave trade in Britain (Finley 1999, 131-154). The engraving showed 454 black bodies arranged within the oblong outline of a ship. Later instantiations of the Brookes incorporated advanced representational conventions of naval architecture: plan, cross-section, and projected views (Wood 1997, 222-223). The technical drawings of the Brookes vividly demonstrated the spatial logic of transporting slaves (see figure 2). The use of structural, design and operational information of the ship gave the ‘Description’ its political legibility and salience (Ibid., 218). For instance, Wood notes that the composition follows Dolben’s Bill regarding the acceptable spacing of slaves during transport (Ibid., 2018); and, in doing so renders cultural and institutional responsibility for the slave trade unavoidably visible.

Fig. 2. Description of a Slave Ship, 1789, In Black Art and the Aesthetics of Memory, by Cheryl Finley (Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, 1969)

The London Committee of SEAST, along with other abolitionist groups throughout England, France, and the United States, deployed the ‘Description’ through a variety of media, the popular dissemination of which was responsible for generating public disgust and political motivation to critically engage with issues surrounding the slave trade (Finley, 1999.131-154). Parson illustrates how the aesthetic capacity of the drawings to convey a neutral factuality, to the otherwise politicized matter of the slave trade, allowed the materials to be disseminated and discussed more easily within intellectual and public circles; though, not beyond the limits of existing hierarchies of gender and sex (2000, 125-128). To that extent, the ‘Description’ and its instantiations played an important role as visual propaganda in support of the first wave of the British Abolition movement (see: Wood 1997, Finley 1999). Critical analysis of the ‘Description’, however – its aesthetic strategies and context within the discourse of the European Enlightenment onwards – provides a more nuanced narrative of how the concept of race, difference, and hierarchies of domination were created and stabilized by the social processes that made the Brooke’s drawings effective and enduring icons of colonialism and racial capitalism.

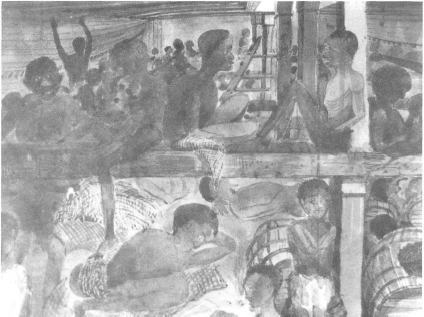

The aesthetic qualities of the ‘Description’ arguably gave the work its initial influence within British culture, circa 1780-1807. These tactics, conventions of representation, and accompany media were effective in part because they communicated an idealized, white-perspective of the economic irrationality of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (Parsons 2000, 170). Parsons notes that the medium for raising awareness about the British slave trade, and importantly what subjects were made visual, versus those that were deliberately made invisible, highlights how representations worked to produces a dialectic of black-naturalness and white-civilization (167-196). This productive function of the visual media is evidenced most starkly in the composition of the ‘Description’, on which Wood identifies: the abstract relationship between negative space and black figures inscribes the slave ship as space void of human presence, a denial of the “flesh and blood presence of the slaves” (Wood 1997, 222). The abstract quality of the ‘Description’ is an absurdity, best understood as the European idealization of the subject, where the reality of a slave ship was entirely different. Representations of these spaces and subjects based on embodied experience, rather than these theoretical statements, are rare. Visual examples, though from a free and white gaze, include the 1846 drawing View of the Deck of the Slave Ship Albanez (Fig. 3). Whereas written records, primarily of medical reports taken aboard slave ships, give literary insight into the actual severity and grotesqueness of the slave ship (see: Sheridan 1981)

Fig. 3. 1846. View of the Deck of the Slave Ship Albanez. Detail. Watercolour drawing. Lieutenant Godfrey Meynell. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, In Imaging the Unspeakable and Speaking the Unimaginable: The ‘Description’ of the Slave Ship Brookes and the Visual Interpretation of the Middle Passage, By Marcus Wood (Freedom and Boundaries, 1997)

The ‘Description’s unrealistic portrayal of the Brookes was not out of place in the first wave abolition movement. The representation aligned with the SEAST agenda, and most mainstream abolitionist groups, namely: to end the slave trade on economic grounds and in the protection of white sailors against the risks inherent to overcrowded boats and sailing (Wood 1997, 213-215). That is, instead of the realization of the emancipation and legal protection of enslaved African peoples. Moreover, the schematic negates the complex and brutal subjectivity of the experience of the slave ship, in favour of portraying black bodies as passive objects of European purview: exemplifying the need of abolitionist culture to first produce the concept of black cultural-absence – a “living death” – as a precondition wherein to negotiate the terms of white guilt (Ibid., 217). The aesthetic strategies used to advance this agenda, draw attention to the fact that the ‘Description’ is a form of political technology adhering to Mbembe’s notion of the Necopolitical (Mbembe 2019, 10-20). Though perhaps for tactical reasons, the designers of the ‘Description’ effectively minimized and distorted the cultural contingency of enslaved people. In doing so the image contributes to the social processes and systems of knowledge that act to erase persons and produce blackness, as a cultural and economic subjectivity of the colonial project. Following through with Mbembe’s logic, the production of the homogenous and anonymous black population was not an aberration within history, mobilized through the abolitionist movement, but more accurately a technical requisite for contributing to the very idea of civilization, progress, and of European industrial capitalist democracy.

For Sylvia Wynter, the notion of what it is to be human is organized through social productions of knowledge and ideas (Wynter 2001, 30-60). To that extent, the ‘Description of a Slave Ship’ should be seen to have simultaneously helped British abolitionists succeed in ending the slave trade, by linking ideas of progress, labour, and capital; and, aided in producing black subjectivity, as a necessary and contrasting condition to the existence of whiteness and cultural progression towards a democratic European civilization. The point of tension identified around the legacy of the ‘Description’ illustrates that representation is an important and potent tool for thinking about and making the world. From this perspective, representations of the Brookes, and the iconography of the slave ship more broadly, are understood as producers of political and cultural meaning, as well as lived experience.

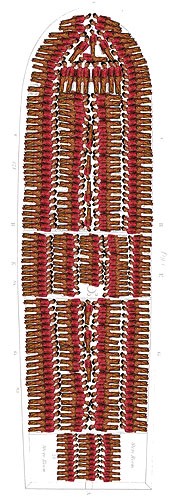

Figure 4. Skowmon Hastanan, Ship Fever Red Fever (Thai Chitralada), 1999–2002. Inkjet print, 8 ½;11 inches. In The Brooks Slave Ship Icon: A ‘Universal Symbol’, By Jacqueline Francis, (Slavery & Abolition, 2009)

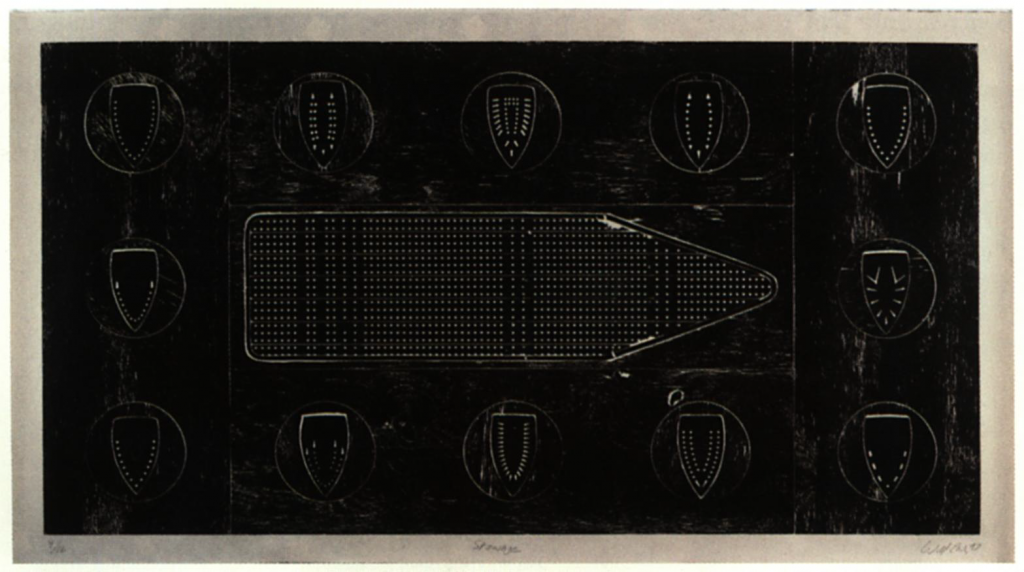

Willie Cole, Stowage (1997) Woodblock print with metal relief printing on Kozo-shi paper (56″ x 104″), In Visual Legacies of Slavery and Emancipation, By Cheryl Finely (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014)

The effects of this dialectic are observed still in contemporary expressions of the post-colonial realities of racial capitalism and the negotiation of black-identity (fig. 4-5). These current instantiations, and the rich literature on their genealogies (see: Finley 2019; Francis 2009), further demonstrate that critical analysis can help dismantle the forms of representational idealization which help stabilize the regime of domination that perpetuate processes of subjection. This insight also illustrates that architecture, as a cultural practice embedded within the European Enlightenment and coloniality, is fundamentally involved in the social and epistemological processes that structure the subjugation, commodification, and exploitation of racial identity. The fact that the discussed image of the slave ship works to ontologically differentiate the black body from the citizen, demonstrates a direct link between the ‘Description of a Slave Ship’ and, for instance, the dumbwaiter’s function in Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, to divide a rational and educated public from a natural slave (Martin 2020, 59-78). More than an effective image in promoting the abolition of the slave trade, the ‘Description of a Slave Ship’, shows that representations of the world contribute to shaping the world. Accordingly, architectural representations, throughout which idealization holds a significant role, should be closely and critically examined for what they make visible, and that which they make invisible.

Sources

Finley, Cheryl. 2014. “Visual Legacies of Slavery and Emancipation.” The Johns Hopkins University Press 37 (4): 1023–32. 2017.

Finley, Cheryl, 2019. “1969: Black Art and the Aesthetics of Memory.” In Incidences de l’événement : Enjeux et Résonances Du Mouvement Des Droits Civiques, edited by Claudine Raynaud and Hélène Le Dantec-Lowry, 131–54. Cahiers de Recherches Afro-Américaines : Transversalités. Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais.

Finley, Cheryl. 2019 “Visualizing Protest: African (Diasporic) Art and Contemporary Mediterranean Crossings.” Journal of Transnational American Studies 10 (1).

Francis, Jacqueline. 2009. “The Brooks Slave Ship Icon: A ‘Universal Symbol’?” Slavery & Abolition 30 (2): 327–38.

Mbembe, Achille. 2019. “Necropolitics”. Durham, US : Duke University Press.

Martin, Reinhold, 2020. “Drawing the Color Line” In Race and Modern Architecture, Edited by Irene Chend, Charles Davis, Mabel O’ Wilson, 59-78, University of Pittsburgh Press.

Parsons, Sarah. 2000. “Imagining Empire: Slavery and British Visual Culture, 1765–1807.” Ph.D., United States — California: University of California, Santa Barbara.

Sheridan, Richard B. 1981. ”The Guinea Surgeons on the Middle Passage: The Provision of Medical Services in the British Slave Trade.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 14 (4): 601–25.

Wood, Marcus. 1997. “Imaging the Unspeakable and Speaking the Unimaginable: The ‘Description’ of the Slave Ship Brookes and the Visual Interpretation of the Middle Passage.” Freedom and Boundaries 16.

Wynter, Sylvia. 2001. “Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, Identity, the Puzzle of Conscious Experience, and What It Is like to Be ‘Black.’” In National Identities and Sociopolitical Changes in Latin America. New York: Routledge.

One reply on “The Slave Ship and The Making of Blackness”

This is a time conserving life changer!