In 1595, the Dutch arrived in the archipelago of Indonesia as part of their voyage of obtaining natural resources1. The Dutch began settling, and continued to establish trading posts around the islands, slowly beginning their 350-year-long colonization. Cities were built around ports, endorsing the trading of goods. With the arrival of the Westerners, comes an inevitable cultural exchange that is significant and still prevalent to this day. One of the evidence of these cultural exchanges can be seen through architecture, and the contributions of Dutch in the urban landscape of the domestic land. As the emergence of modern cities is hinged by the arrival of the Dutch, urban design and architecture became key in understanding how the Dutch began establishing their long colony in Indonesia. This essay will follow an architectural heritage, The Palace of Daendels, in an exploration of Dutch colonial architecture in Indonesia and how it has evolved over the years in the culture of the modern nation.

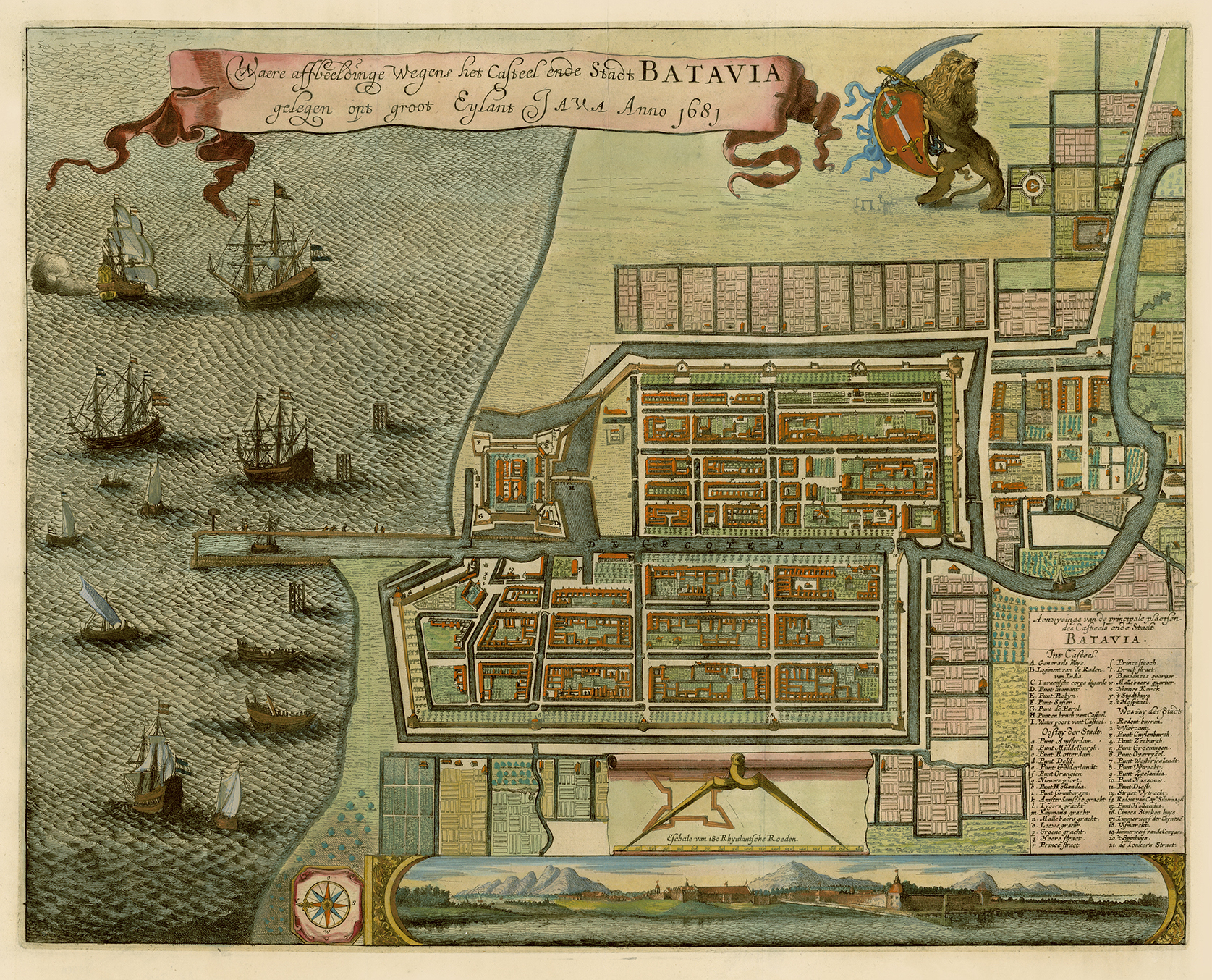

Building a palace as the center of government is a symbol of power and dominance for the Dutch colony. Therefore, since the arrival of the Dutch in the island, the building of institutional buildings was of great priority in further signifying their dominance. The idea of building the Palace of Daendels arose when the 1732 Malaria epidemic hit the old town of Batavia2. Unhealthy, the decaying city was densely populated and was no longer ideal to be the central district of the capital. The ambitious governor-general, Herman Willem Daendels, ordered the move of the central government to the suburbs of Weltevreden and, in 1809, ordered the construction of the Palace of Daendels3. The Palace of Daendels was built as the new governor’s residence and was imagined to be the new city center of new Batavia4. The construction of the palace, which was also known as the Great House, was tedious as blockades by the English presented difficulties in gaining materials for the building5. With the lack of resources, Daendels ordered the demolition of all the buildings in Old Batavia to reuse as the materials to build the new city of Batavia. These demolished buildings of Old Batavia included the Kasteel Batavia (which was the previous administrative center of the Dutch East India) and buildings that were erected during the pre-colonial period of the Dutch6.

The appointed architect for the palace was Lieutenant Colonel JC Schultze Guga, who was at the time one of the renowned architects7. The architect translated the palace into three two-storey buildings with a plan that reveals a grand residential palace flanked with left and right wings intended for administration, guest houses, and a stable for horses. As Daendels represents Napoleon Bonaparte in the Dutch East Indies, the architect adopted the French neoclassical Empire Style which was prevalent in France at the time. Adjusting to the tropical climate of Indonesia, the adopted Empire Style evolved into a subsequent hybrid later identified as the Indies Empire Style8. This style typically features a large roof overhang, tall ceiling, and front and rear verandas that connect to the garden. With a style that is reminiscent of Europe, the Dutch attempted to establish their home without culturally appropriating to its context. As the construction for the Palace of Daendels required a long period of time, the governor-general resides at the Bogor Palace while the palace is being constructed. Unfortunately, Daendels was ordered by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1811 to command the Grande Armée in Europe, and was forced to stall the development of the project9. During the administration of Jan Willem Janssen, the successor of governor-general Daendels, the building was only half finished and very minimal progress was made in the construction. It was only during the administration period of Leonard Pierre Joseph du Bus de Gisignies in 1826 that the palace resumed its construction. Under Du Bus, the new architect Ir. J. Tromp was appointed10. With the determination of Du Bus in completing the project, the palace was finally completed in 1828, just 2 years after the restart, and 19 years since it first began construction11. With its white walls, strict symmetrical form, pilasters, and extended size of windows, the building refers to the palaces of northwest Europe, and the adaptation of the Empire Style is clearly evident. Upon completion, the Palace of Daendels became the new icon of Batavia, and was commemorated in a plaque written: “MDCCIX – Condidit Daendels, MDCCCXXVIII – Erexit DUBUS” as an homage to the governor-generals that realized the building12.

Despite the completion of the palace, the building was found to be too small and inefficient, and therefore was never used as the governor’s palace like it was initially intended13. In 1869, a new governor’s palace was ordered and the Palace of Daendels became the house for various governmental offices such as the post office, the state printing office, and the high court14. In the late 1950s, the building became the headquarters of the Ministry of Finance of Indonesia and remains as the office to the present day15. The Palace of Daendels is one of many administrative colonial buildings that is still being used to this day. In general, the discourse around colonial built heritage has been sensitive and complex, involving political and ideological discussions that are often tied with feelings of anguish, uneasiness and condemnation. In Indonesia however, this antagonistic view towards colonial heritage has drastically shifted for the better in the past two decades16. Colonial buildings are often seen as striking, efficient, and grand. The positive attitude towards colonial heritage in Indonesia is commendable, as even though the built heritage serves as reminders of foreign dominance, there is still an appreciation and awareness towards the historical artefacts. This positive outlook on colonial heritage can be attributed to the increasing number of scholarly and popular publications of colonial history17. Additionally, the appropriation by Indonesia and the Netherlands of their colonial built heritage has also been instrumental in promoting awareness towards the issue18. Both countries have unravelled the deep layers of their colonial history and architecture, laying down the foundations for a more open and optimistic discussion around the colonial history of architecture and urban planning.

The examination of the Palace of Daendels and its colonial history can be a window in further exploring the subject of colonial architecture in Indonesia. The study provided insight as to how architecture is being used as an instrument of power and superiority. Understanding the processes and history behind the realization of the architecture have highlighted the dominance and power that the Dutch possess over the colonized nation. Moreover, the adjustment of the European style to its tropical context that is merely serving the purposes of climate, and not culture, is evident to the exclusive attitude of colonial architecture. However, despite the dreadful background, the modern Indonesian population has grown to accept and appreciate its colonial heritage as Indonesia and the Netherlands have helped substantiate the discourse of the subject. Perhaps, this established interest and positive view towards colonial history and its built heritage could spark further conversations about architecture and colonisation that is more progressive and beneficial in the study of architectural history.

Footnotes

1. “Dutch Colonization,” Indonesia Imperialism, accessed February 22, 2021, https://imperialismindonesia.weebly.com/dutch-colonization.html#:~:text=The%20Dutch%20arrived%20in%20Indonesia,a%20place%20to%20take%20over.

2. Yudhistira Mahabarata, “Daendels Builds The White Palace He Never Lived,” Waktunya Merevolusi Pemberitaan (VOI.ID, October 28, 2020), https://voi.id/ar/memori/18205/daendels-builds-the-white-palace-he-never-lived.

3. Mireille van Reenen, “Daendels’s Self-Tempered Ambitions. An Architectural Analysis of the Government House in Weltevreden (the Present Jakarta),” Bulletin KNOB, December 1, 2005, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.104.2005.6.266.

4. Ibid.

5. Yudhistira Mahabarata, “Daendels Builds The White Palace He Never Lived,” Waktunya Merevolusi Pemberitaan (VOI.ID, October 28, 2020), https://voi.id/ar/memori/18205/daendels-builds-the-white-palace-he-never-lived.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Hanandito, “Indische Empire Style’ – the Endangered Tempo Doeloe Architecture Style,” DIMENSI – Journal of Architecture and Built Environment, 1994, p. 20.

9. Dinas Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan DKI Jakarta, “Palace of Daendels,” Palace of Daendels, accessed 2AD, http://encyclopedia.jakarta-tourism.go.id/post/Palace-of-Daendels?lang=en.

10. Ibid.

11. Yudhistira Mahabarata, “Daendels Builds The White Palace He Never Lived,” Waktunya Merevolusi Pemberitaan (VOI.ID, October 28, 2020), https://voi.id/ar/memori/18205/daendels-builds-the-white-palace-he-never-lived.

12. Ibid.

13. Dinas Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan DKI Jakarta, “Palace of Daendels,” Palace of Daendels, accessed 2AD, http://encyclopedia.jakarta-tourism.go.id/post/Palace-of-Daendels?lang=en.

14. Ibid.

15. Mireille van Reenen, “Daendels’s Self-Tempered Ambitions. An Architectural Analysis of the Government House in Weltevreden (the Present Jakarta),” Bulletin KNOB, December 1, 2005, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.104.2005.6.266.

16. Pauline K. M. van Roosmalen, “Confronting Built Heritage: Shifting Perspectives on Colonial Architecture in Indonesia,” ABE Journal, no. 3 (February 2013), https://doi.org/10.4000/abe.372.

17. Ibid

18. Ibid

Bibliography

Dinas Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan DKI Jakarta. Palace of Daendels, n.d. http://encyclopedia.jakarta-tourism.go.id/post/Palace-of-Daendels?lang=en.

“Dutch Colonization.” Indonesia Imperialism. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://imperialismindonesia.weebly.com/dutch-colonization.html#:~:text=The%20Dutch%20arrived%20in%20Indonesia,a%20place%20to%20take%20over.

Hanandito. “Indische Empire Style’ – the Endangered Tempo Doeloe Architecture Style.” DIMENSI – Journal of Architecture and Built Environment, 1994, 20.

Mahabarata, Yudhistira. “Daendels Builds The White Palace He Never Lived.” Waktunya Merevolusi Pemberitaan. VOI.ID, October 28, 2020. https://voi.id/ar/memori/18205/daendels-builds-the-white-palace-he-never-lived.

van Reenen, Mireille. “Daendels’s Self-Tempered Ambitions. An Architectural Analysis of the Government House in Weltevreden (the Present Jakarta).” Bulletin KNOB, December 1, 2005. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.104.2005.6.266.

van Roosmalen, Pauline K. M. “Confronting Built Heritage: Shifting Perspectives on Colonial Architecture in Indonesia.” ABE Journal, no. 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4000/abe.372.

Images

Fig 1. ANTIQUE MAP BATAVIA BY LETI (C.1690). n.d. Bartelle Gallery. https://bartelegallery.com/shop/antique-map-batavia-by-leti/.

Fig 2. Waterlooplein. n.d. Merah Putih. https://merahputih.com/media/68/3f/51/683f5186d475d7fa2324423ba562b134.jpg.

Fig 3. Peleis Van Daendels. n.d. REQNews. https://www.reqnews.com/memoar/1894/kala-daendels-lakukan-reformasi-hukum-di-tanah-jawa.

Fig 4. The A.A. Maramis Building, Formerly Dubbed the Witte Huis or Gedong Putih, the “White House”. n.d. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A.A._Maramis_Building.