Pre Existing Native Hawaiian conditions allowed for the rapid industrialization of the Big Island of Hawaii and surroundings Islands, Capitalized on by John Parker and the Parker Ranch.

The Parker Ranch, on the Big Island of Hawaii, is one of the oldest Ranches in North America, pre-dating many Mainland Ranches by more than 30 years. The Parker Ranch and dynasty in Hawaii was monumental in the history of the modern State of Hawaii, playing a prominent role in the beginning of industry and surplus production on the islands. However, I argue that the Native Culture of the Hawaiian Islands practiced what is now known as ranching, long before western-contact and the establishment of the Parker Ranch. Not only did this culture exist, but it was the foundation in many ways for the ranching system in Hawaii and later the continent. Finally, the establishment of the Parker Ranch marked a critical shift in Hawaii; taking a practice centered on sustainability and conservation, and strategically transforming it into a commercial and industrial machine, to the dismay of the natural environments and island communities.

The impact of Native Hawaiian life on the Parker Ranch is still visible today, through both surviving infrastructure from native communities, as well as lasting borrowed systems still used in modern day Hawai’i. Many architectural clues help to tell the story of the Parker Ranch and what went into it, from original agricultural Lava Walls (Figure 1), still visible on the shores of most Hawaiian Islands, to long vertical plots running from the center of the island all the way out to the deep sea fishing grounds, still referenced today. Additionally, it is easy to find conflicting styles of architecture from this era, from Parker’s own East-coast style Salt-Box house to traditional Hawaiian construction using natural wood and twine; however, the story of the Parker Ranch is much better understood when considering the relationship between these two cultures, rather than the differences.1

1. Bergin, Billy. Loyal to the Land: the Legendary Parker Ranch, 750-1950: Aloha 'Āina Paka. Honolulu Hawaii, HI: University of Hawai'i Press, 2004.

Land Division and Ownership

Firstly, and most dramatically visible on a large scale, are the interesting shapes of ‘land’ plots seen on most Hawaiian Islands, both before and after contact with the colonizing West. The Big Island of Hawaii, where Parker Ranch eventually settled, had been using a vertical system of land-distinction for an estimated 500 years (1100-1200 ad.) before first contact with the new world. In Native Hawaii, land “custody” was divided amongst local chiefs and their supporters, into local districts, or ‘Moku’. These districts were long, narrow plots that “typically extended from the high forest mountains to offshore fishing grounds, providing residents with access to the resources of all elevations, without crossing borders.” 2 The Big Island of Hawaii has many climates: using the Koppen Climate Classification Scheme 3, it has 8 of 13 sub climates existing in the world, from Tundra to Monsoon (Figure 3). For this reason, the vertical distinction of land was very crucial because it allowed the majority of communities access to dramatically varying climates of the island, and thus varying production and harvesting methods. The fish from the deep sea to the birds collected on the edges of the tundra for the feathers, and all the varying plant life in between, was all within one district’s land.

The Parker Ranch and many surrounding ranches began to develop in similar ways to the vertical plots of land seen in old Hawaii, for mostly similar reasons. The range of climates gave rise to tremendous opportunity and variety for production. Additionally access to the sea was still crucial for ranching, less so for traditional fishing grounds, and more so for inter-island trade and the eventual export of products off-island, mostly to continental US and Europe. However, the major difference between Native Hawaii and what was to become the State of Hawaii was the idea of Land Ownership. In Native Hawaii, the relationship between the people and the land was “one of territorial custody, rather than land ownership. It was said that land could not belong to man because man belonged to the land.” 4 Instead, the practice was for locals to take care of the land they occupied, and in return the land and the chiefs of that land would take care of them. The Great Mahele in 1848, was a land division plan implemented by King Kamehameha III of the Hawaiian Monarchy, highly suggested by his colonial advisors. The proposition was intended to secure land for local Hawaiians, amongst raising industrial pressures and immigration from colonizing forces, through the novel idea (to Hawaiians) of land ownership. However, in practice, due to the local inexperience with the concept, the plan would eventually end up separating many local Hawaiians from their land. In a lecture delivered at the Kamehameha Schools, John H. Wise describes the local Hawaiian people before the Mahele as “so accustomed to generations of communal rights, to forest upland produce, to fishing and to land, they could not imagine life on another basis. The whole idea of fee simple ownership was so new to them, that they could not comprehend it or take advantage of it.” 5 Simultaneously, as many locals failed to lay claim to any land at all, and many of those who did sold it off, foreigners and colonizers slowly started to build up land collections, one of whom was John Parker from Parker Ranch. Although the new concept of buying, selling, and leasing land did separate locals from their homelands, and impede on the traditional vertical division of land through ‘Moku’, new colonial settlers, notably Parker, still maintained the basic theory of occupying large elevations of land for the same benefits enjoyed by Native Hawaiians.

2. Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997. “The Land” Page 31. 3. Peel, M. C., B. L. Finlayson, and T. A. McMahon. “Updated World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. Copernicus GmbH, October 11, 2007. https://hess.copernicus.org/articles/11/1633/2007/hess-11-1633-2007.html. 4.Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997. “The Land” Page 31. 5. Wise, John H. Essay. In Ancient Hawaiian Civilization: a Series of Lectures Delivered at the Kamehameha Schools, Chapter 7. Honolulu, HI: Mutual Pub., 1999.

Conservation and Production: The Great Kapu

Along with land division and ownership was a shift from conservation to production, with Native Hawaii transitioning into the American State of Hawaii. The Native Hawaiians, while living entirely off the land, still practiced conservation. The Kapu was a method which placed protection over certain species (animals and plants) during important times in their development, for example spawning for fish and fertilization for plants, or more generally a ban on harvesting for half of the year to allow population re-growth of heavily targeted species. It is suggested that the Kapu was “possibly a lesson learned from the disappearance of large flightless seabirds early [polynesian] settlers had hunted to extinction”6. Nevertheless, Native Hawaii was well connected to the idea of conservation and the health of their land; however, ironically this was the same practice that gave rise to the concept of ranching on the islands, and eventually, when paired with land ownership, the switch from conservation to mass production.

The life of John Parker and the creation of his Parker Ranch relied almost entirely on an infamous Kapu. In 1793, Captain George Vancouver arrived on the big island of Hawaii with a gift of cattle for King Kamehameha I. For the next 20 years, these cattle and their subsequent relatives were protected by King Kamehameha and the Kapu, “the law- carrying the death penalty – that would apply to anyone causing the demise of any cow, bull, calf, steer, or heifer yearling.” 7 By the time John Parker himself made the Big Island of Hawaii his home in 1815, wild cattle had overrun the Island, wreaking havoc on Hawaiian life, and the Kapu had been lifted. In his extensive work on Parker and his Ranch, Loyal to The Land, The Legendary Parker Ranch, Billy Bergin describes Parker’s Chance encounter that lead to his success as a Rancher:

“Parker earned his appointment as the king’s first authorized cattle hunter. He was able-bodied and capable and had behind him years of experience to prove his trustworthiness. In his favor was the king’s knowledge that Parker possessed a musket with ammunition, along with the skill necessary for its effective use. His marriage to Chiefess Kipikâne undoubtedly placed Parker in an advantageous position.”8

Be the primary reason his relationship to the King’s Granddaughter, his possession of a modern musket, or a combination of the two and more, John Parker used his exclusive right to not only hunt cattle, but also to supply the meat and hides for both local and foreign consumption, and rose the ranks of the island quickly, amassing wealth and influence just as quickly as the cattle industry. By 1830, the entire island of Hawaii was participating in the cattle industry which had become the island’s major export. Additionally, Parker was born an East Coast American and was not foreign to the concept of land ownership and the free-market like his Hawaiian counter parts, and was able to take full advantage of the Mahele, or new ability to acquire land in Hawaii, further fueling the perfect storm that lead to the Parker Ranch. By the mid 1850s, 40-60 whaling ships docked at Parker’s kawaihae harbour, “taking abroad 1500 barrels of salt beef, 5,000 barrels of sweet potatoes, 1,200 bullock hides, and 35,000 pounds of tallow on an average,” annually9. The days of Hawaiian’s conservation were ending, and production for profit had begun. Previously, “when Hawaiians worked, they worked impressively, but when their needs were met, they ceased working”. This was perceived as laziness to European Colonizers, and not as conservation of the Land. Therefore, the lush, cultivated islands of Hawaii began to produce to their maximum potential, and left behind the sustainable Native system that had done the cultivating. 10

6. Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997. “Fishing” Page 74. 7. Bergin, Billy. Loyal to the Land: the Legendary Parker Ranch, 750-1950: Aloha 'Āina Paka. Honolulu Hawaii, HI: University of Hawai'i Press, 2004. Page 22. 8. Ebid 7, Page 28. 9. Bergin, Billy. Loyal to the Land: the Legendary Parker Ranch, 750-1950: Aloha 'Āina Paka. Honolulu Hawaii, HI: University of Hawai'i Press, 2004. Page 32. 10. Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997. “Reciprocity” Page 42.

The Marriage of Two Cultures

As much as land ownership, and ideas of mass production affected the transformation of Hawaii, the two combining cultures, that of local Native Hawaiins, and the later of colonizing forces, interacted in very unique ways to cause the slow, fairly stable, takeover of Hawaii.

Throughout colonization, many native communities were reduced to the title of savages, because their culture and life practice were so far removed from the industrialized colonizers that their simplicity in necessity was incomprehensible. However, in the case of Hawaii, architectural development, complex agricultural systems, and a clean and healthy lifestyle, showed an ingenuity in the culture that colonizers respected, and in many ways adopted. Intercultural marriages and foreigners learning to communicate in Hawaiian language was commonplace, and accurate in the case of John Parker. Initially western immigrants mostly worked with hawaiian culture and brought with them new inventions and technologies that aided in much of the current cultural activity. A main example of this was the employment of John Parker and his modern musket, by King Kamehameha.

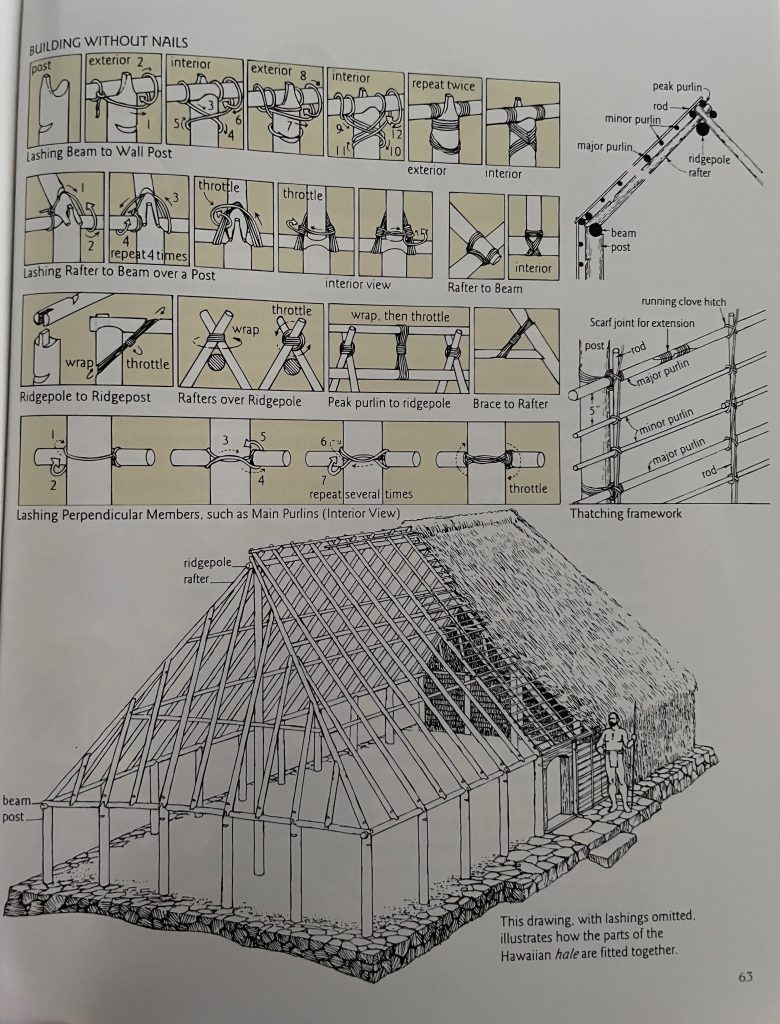

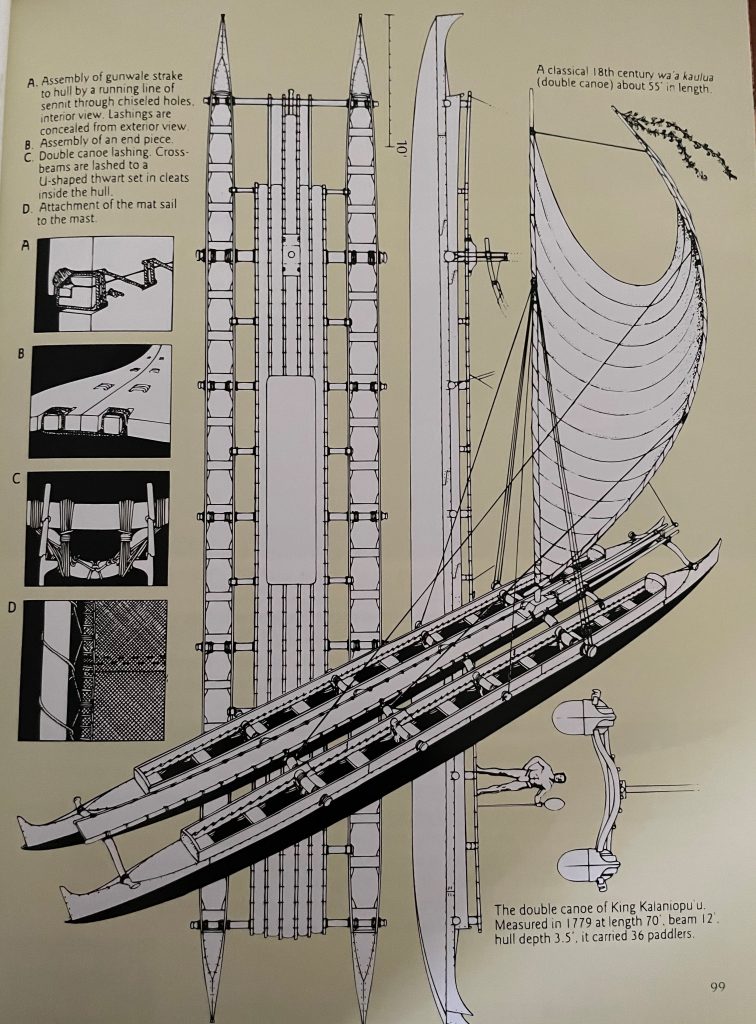

The physical structures that lined the shores of Hawaii, were focused and delicate in construction, featuring “intricate sennit lashings [that] are decorative as well as functional” (Figure 6).11 Large temples and chief residences rose above the landscape on lava wall foundations, mortared with sand and small stones (Figure 7), with “freshly cut grass spread under top mats”, on the interior of these structures, that “adds softness and fragrance”. “At the time of European contact in AD 1778, chiefs in the Hawaiian archipelago had implemented a temple network to provide the proper infrastructure for expressing the ideology of kingship, feudalizing land tenure practices, imposing ritual taboos on labor and production, and engaging in internecine warfare over territory.” 12 Furthermore, advanced construction techniques of canoes (Figure 8), encountered far out to sea easily navigating, long before the sight of the first islands, further the perception of this advanced, yet non-westernized civilization, in the eyes of colonizers.

These technological displays continued to agriculture, where Lava-walled pens of pigs and chickens, amongst intensive planted plots “wherever topsoil is present” 13, resembled the ranching culture to come, long before the term ‘ranch’ would be adopted. These fine tuned architectural and cultural elements showcased a culture for incoming colonizers to join and ‘progress’, as opposed to overthrow and suppress. Of course, this was not without influence that eventually led to the demise of many Native Hawaiian communities. An example of architectural influence was seen in John Parker’s proud display of his East-Coast style salt-box house (Figure 9), practically transported from his home in Newton, Massachusetts, to the hills of Big Island, Hawaii, despite his marriage to Hawaiian royalty and close relationship to the King.

While colonizers still eventually annexed Hawaii and displaced much of its existing culture, the initial merging of the two cultures allowed the colonizing forces to exert a slow and relatively peaceful takeover, while ultimating still benefiting from native knowledge, and displacing local peoples simultaneously. Specifically so, in the case of John Parker and development of the Parker Ranch (1817 – present).

11. Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997. “Ancient Landscape” Page 62. 12. Kolb, Michael J. “The Origins of Monumental Architecture in Ancient Hawai‘i.” Current Anthropology 47, no. 4 (2006): 657–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/506285. 13. Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997. “Ancient Landscape” Page 65.

Works Cited;

Bergin, Billy. Loyal to the Land: the Legendary Parker Ranch, 750-1950: Aloha ‘Āina Paka. Honolulu Hawaii, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004.

Kane, Herbert Kawainui. Ancient Hawaiʻi. Captain Cook, Hawaiʻi, HI: Kawainui Press, 1997.

Kolb, Michael J. “The Origins of Monumental Architecture in Ancient Hawai‘i.” Current Anthropology 47, no. 4 (2006): 657–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/506285.

Lincoln, Noa, and Thegn Ladefoged. “Agroecology of Pre-Contact Hawaiian Dryland Farming: the Spatial Extent, Yield and Social Impact of Hawaiian Breadfruit Groves in Kona, Hawai’i.” Journal of Archaeological Science. Academic Press, May 24, 2014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440314001861.

Love Big Island. “The 8 (Not 10, 11, 12, or 13) Climate Zones on the Big Island.” Love Big Island, January 15, 2021. https://www.lovebigisland.com/hawaii-blog/climate-zones-big-island/#:~:text=There%20are%208%20climate%20zones%20on%20the%20Big,or%20explained%20in%20Hydrology%20and%20Earth%20System%20Sciences%29.

Peel, M. C., B. L. Finlayson, and T. A. McMahon. “Updated World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. Copernicus GmbH, October 11, 2007. https://hess.copernicus.org/articles/11/1633/2007/hess-11-1633-2007.html.

“Travel, Landscape, and Nature Pictures.” Travel, landscape, and nature pictures – QT Luong stock photos and fine art prints. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.terragalleria.com/.

Wise, John H. Essay. In Ancient Hawaiian Civilization: a Series of Lectures Delivered at the Kamehameha Schools, Chapter 7. Honolulu, HI: Mutual Pub., 1999.