An English landscape garden using an eclectic combination of architectural typologies and building styles.

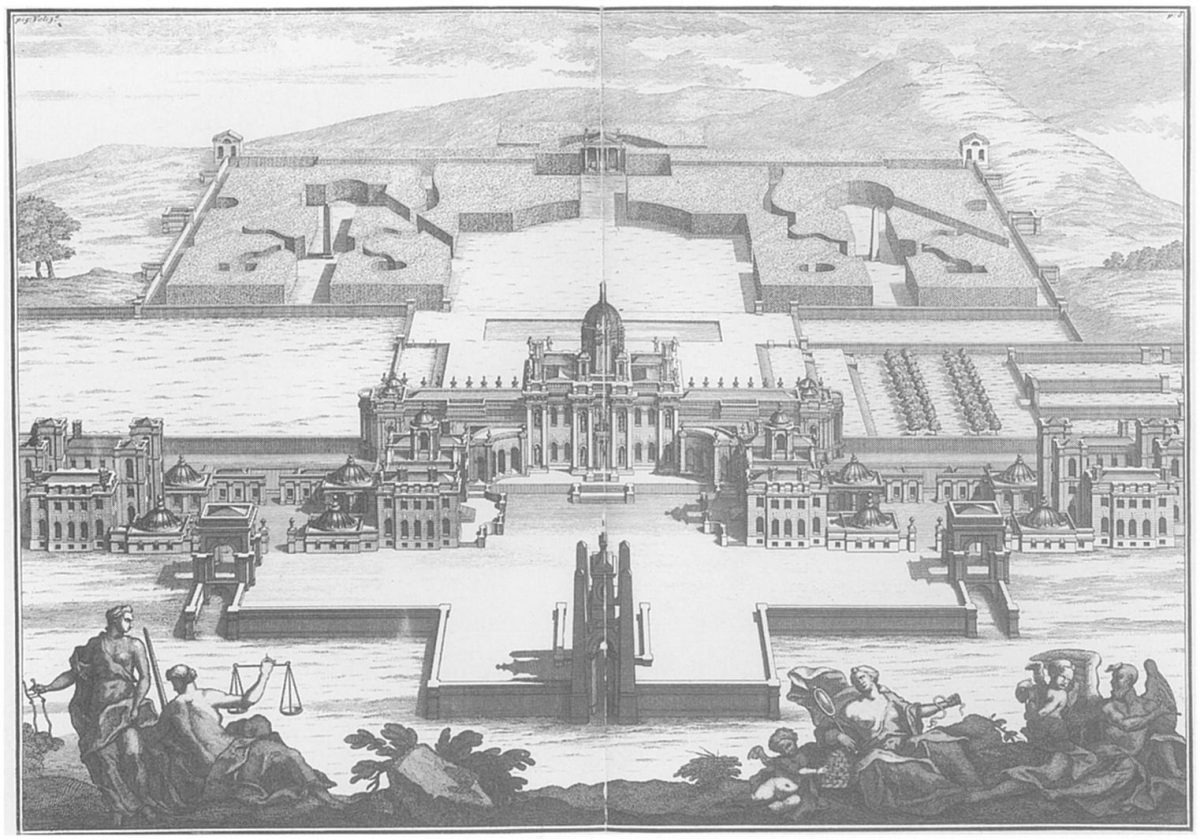

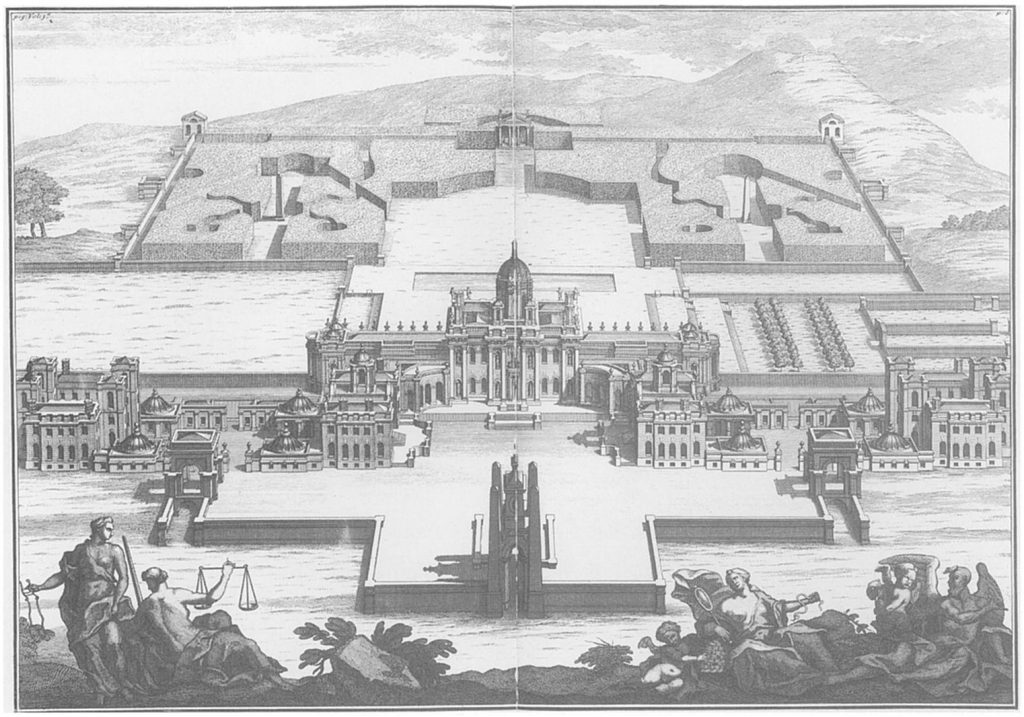

Castle Howard is an English castle and landscape garden located in North Yorkshire. From a first glance, viewers tend to draw their attention towards the magnificent splendour of the castle, without paying much attention to the surrounding landscape. The ornamental architecture of Castle Howard has captured attention in film and television cinematography, and was used in the filming of many shows including Brideshead Revisited (1945) and Netflix’s Bridgerton (2019)1. In each of these series, the landscape and outbuildings were omitted entirely from the production.

The landscape, however, has a multitude of layers that elevate the building’s significance in architectural history. Castle Howard can be classified within the Renaissance-Baroque system of classical architecture, where the appearance of modernism arguably first appeared. This is on the basis of planning the “natural” for a picturesque aesthetic, and mixing various building styles within the gardens. For Castle Howard, these structures experimented with a revival of Gothic Architecture and an eclecticism of historical architectural typologies scattered around the garden2. Most significantly, Castle Howard’s landscape allows for the viewer to hold a subjective stance in the determination of meaning when transcending through the carefully curated garden. Rather unconventionally for an English house, the meaning of the architecture at Castle Howard has been elaborated, extended and subverted so that it becomes unclear what the spectator is intended to be viewing, and what message is being conveyed3. As a result, Castle Howard defined the British country house and influenced how landscape gardens were perceived over the following two decades4.

Background

Lord Carlisle, the owner of Castle Howard, hired architects John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor to design his estate home as an expression of personal and familial ambitions in 16995. Carlisle came from an undistinguished branch of familial history and his desire to build Castle Howard stemmed from the determination to legitimate the status of the Howard Family and display his growing personal power6. Carlisle had approached a few architects, however, unhappy with their proposals, approached Vanbrugh for a better solution. Vanbrugh, in collaboration with the highly skilled and professionally trained architect Hawksmoor, came up with a design that satisfied Lord Carlisle7. The proposal re-oriented the existing house on a north-south axis and celebrated the “naturalness” of the existing Raywood located on the eastern side of the site8. The careful curation of seemingly unrelated winding paths, water systems, and the placement of benches and statues within the garden, aid in revealing the “naturalness” of the gardens.

The building of Castle Howard was not a static operation, requiring many skilled labourers. This included consultants, skilled specialists, masons, carpenters, smiths, ropers, lime burners, carters for transferring supplies, wheelwrights creating the barrels to transfer stone, and labourers specifically required for digging and moving earth9. The main house construction was completed in 1712, which allowed for a shift in focus to the outbuildings and gardens.

The Gardens

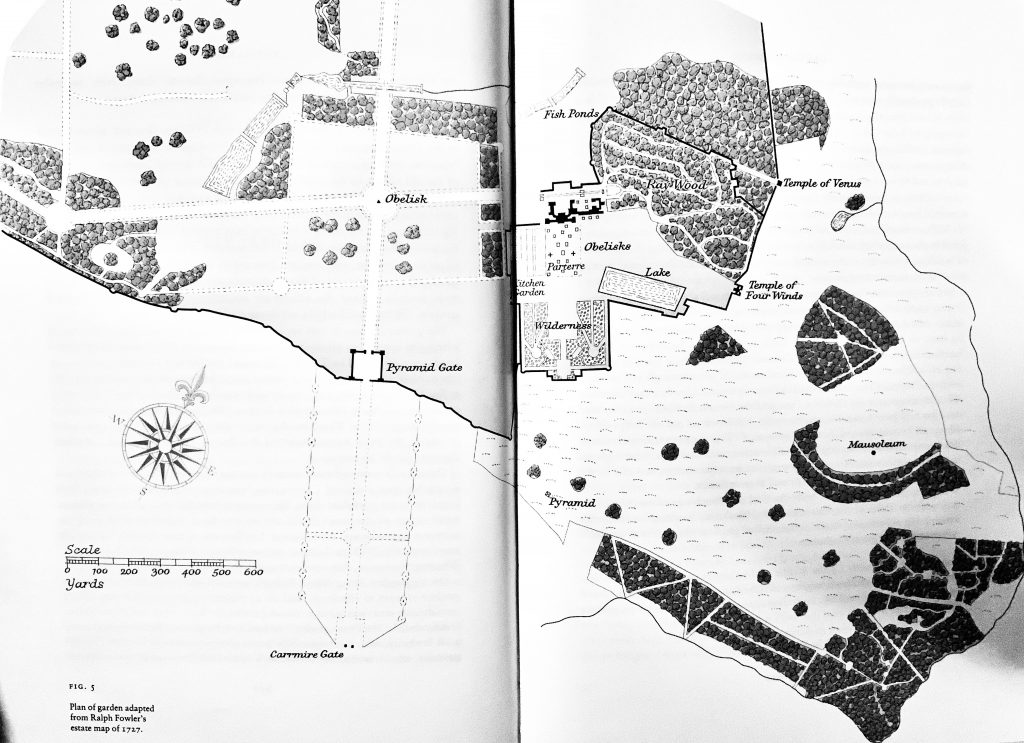

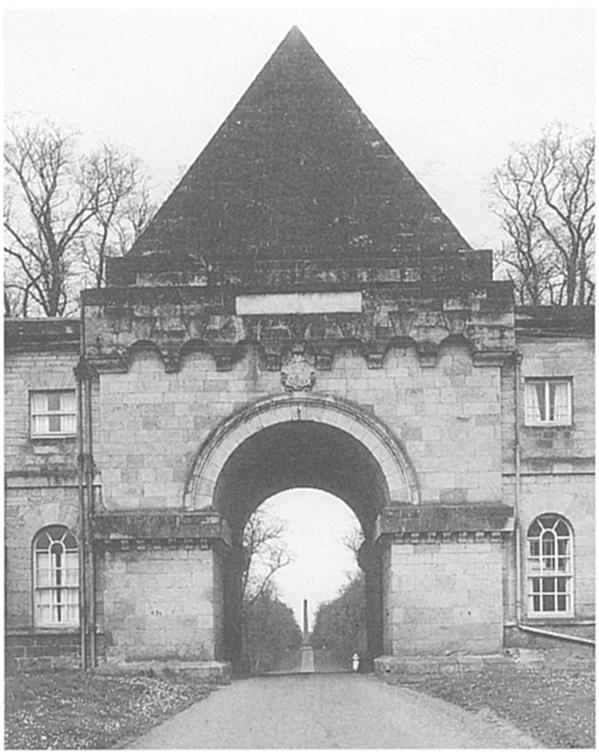

The extension of architecture into the surrounding landscape was a major undertaking, with equal funding allotted to designing the landscape as was spent on the residence itself 10. A central focus in the design aimed to craft and curate a “natural” landscape and focal point of leisure, rather than what had historically been used for productive agriculture. It is important to note, however, that the gardens were not derived from one singular idea, but instead a multitude of ideas applied gradually to different areas of the surrounding typology11. The preliminary garden design began with the erection of the one-hundred-foot high and conventional Obelisk in 1714, symbolizing the building’s approach and main access point. Following this, the Carrmire Gate was completed in the 1730s, built using small, rough-cut blocks. The gate combines historic classical design and medieval-construction in a symbolic attempt to confuse the visitor on the age and extent of Castle Howard12. Adjacent to Carrmire Gate along the same ridge is the Pyramid Gate. The Pyramid Gate represents a departure from standard classical practice, as the entrance has not been defined axially, and instead, aligns to a manmade path. The Pyramid Gate’s combination of ancient Egyptian form that has been superimposed onto a medieval base, represents an aggressive statement of territorial defense13. The vastness of the landscape can be seen upon this entry, expressing power, “naked and unashamed”, over its surrounding landscape.

A relationship can be formed between Castle Howard’s landscape outbuildings and the pictorial representations of artists such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. For Castle Howard, the viewer plays an essential role in the determination of surrounding meaning. It is not evident what the spectator is supposed to be viewing, nor what message is being conveyed. Three main structures were later designed throughout the gardens, the Temple, the Mausoleum and the Pyramid. These were discussed and designed simultaneously over a span of five years, with reference to one another14. These structures have been heavily based off of existing typologies, alienated from their original context and placed within the gardens of Castle Howard as a tool to demonstrate the power of the Howard family.

The Temple

The temple, designed by Vanbrugh, was built based on Palladio’s Villa Rotonda, an appropriate precedent to accommodate views on all directions. Villa Rotonda is considered to be the first Renaissance building that expropriated roman forms for modern domestic purposes15. Similar to the domesticity of Villa Rotonda, Vanbrugh’s Temple also had no agricultural function and instead was intended for only leisure activities. A 26-foot square base is capped with a dome, featuring ionic porticos and statues of Sibyls. The temple is open and well-lit, emphasizing the distant views of the surrounding landscape16.

The Mausoleum

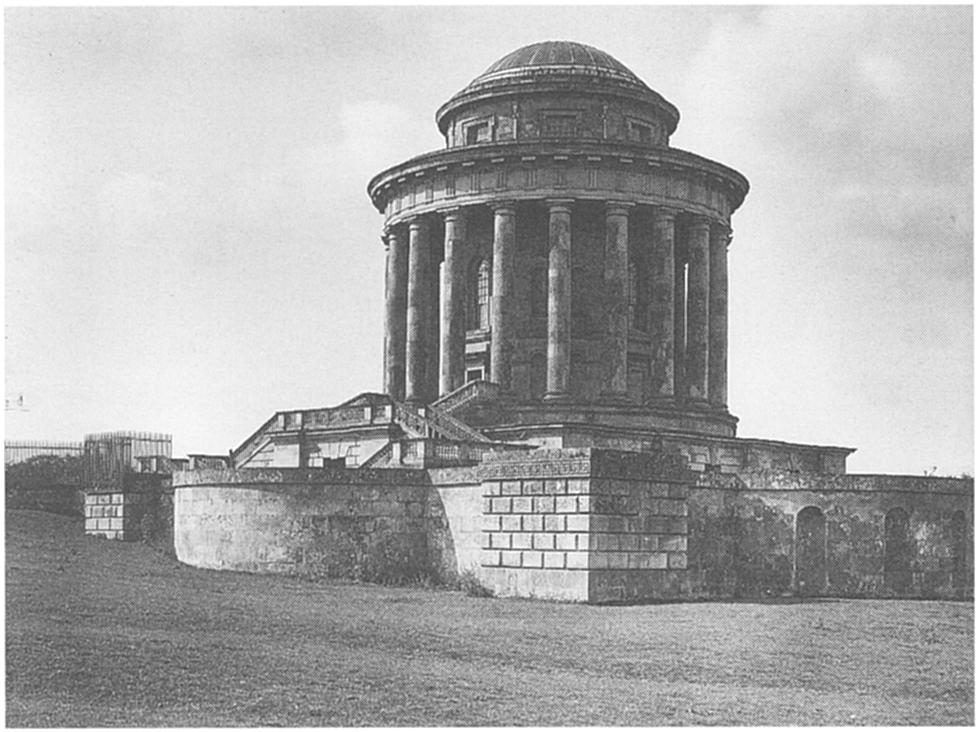

The Mausoleum was the second significant structure built into the landscape, dedicated to preserving the Carlisle family history and lineage and intended to serve an ecclesiastic function17. The main function of the Mausoleum serves to contain the remains of Carlisle, symbolizing monumental architectural commemoration18. Following debate as to what type of building typology the structure should take on, Carlisle and Hawksmoor chose a form dedicated to divine honour, and chose to recreate the Tomb of Caecilia Metella, located on the outskirts of Rome19. The form of the Mausoleum directly relates to ancient Roman and Greek prototypes20. It features a Doric colonnade with a clerestory dome at the centre. The columns are tall and closely spaced, giving the structure a guarded and forbidden appearance. The crypt at the centre is large enough to accommodate seventy coffins21.

The Pyramid

The pyramid, built in 1728, is the third major monument built in Castle Howard’s landscape. It defines itself sepulchrally using the typology of an Egyptian tomb. The pyramid rests in the landscape with no clear approach. Rather than orienting itself conventionally towards the house, the pyramid is not axially centred and instead is rooted in the direction of the temple and Mausoleum22. The pyramid itself only has one small door that opens into the vaulted interior space, and features an inscription on the plaque.

Significance

The order of the landscape at Castle Howard is extremely disconnected. Unlike other landscape gardens being built at the time, no clear paths linked the gardens to the main building. Instead, the distances between the three monumental structures at Castle Howard are extremely vast and lack any clues in regards to their approach. The different character of each of the outbuildings found within the landscape also contributes to the contradiction to the natural landscape. As a result, the visitor plays a more active role in curating the narrative and finding meaning while meandering through the landscape.

The differences between the Pyramid, Mausoleum and Temple contribute to their autonomy and define their significance in relation to the surrounding landscape. Each of the structures declare independence through their geometry, while relating to each other by location and orientation. The temple represents the present by its domestic outlook. The pyramid represents the past in its Egyptian typology. And finally, the Mausoleum represents the future, a place where Carlisle’s heirs are reminded to continue the work that he commenced.

Castle Howard’s eclectic combination of architectural typologies and styles are used to establish Lord Carlisle’s wealth and political power by adopting various Greek, Roman / Italian and Egyptian architectural forms and claiming them as his own by situating them within his landscape garden.

Footnotes

1“The Howard Family.” Castle Howard, Historic House North Yorkshire, accessed April 24, 2021, https://www.castlehoward.co.uk/visit-us/the-house/the-howard-family

2 Levine, Neil. Castle Howard and the Emergence of the Modern Architectural Subject. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 326.

3 Saumarez Smith, Charles. The Building of Castle Howard. London: Faber and Faber, 1990.

4 Levine, Neil. 329.

5 Downes, Kerry. Sir John Vanbrugh. A Bibliography, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1987.

6 Levine, Neil. 334.

7 Downes, Kerry. 124.

8 Levine, Neil. 333.

9 Saumarez Smith, Charles. 87.

10 Ibid, 334.

11 Saumarez Smith, Charles. 149.

12 Levine, Neil. 337.

13 Saumarez Smith, Charles. 132.

14 Vanbrugh to Jacob Tonson, 12 Aug. 1725, in Webb, Letters, 166-67.

15 Ibid, 339.

16 Levine, Neil. 340.

17 Hawksmoor to Carlisle, 16 Feb. 1731

18 Saumarez Smith, Charles. 161.

19 Levine, Neil. 340.

20 Ibid, 343.

21 Ibid, 340.

22 Ibid, 342.

23 Ibid, 345.

24 Ibid, 344.

References

Downes, Kerry. Sir John Vanbrugh. A Bibliography, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1987.

Hussey, English Gardens, 101. Cf. Ronald Paulson, Emblem and Expression: Meaning in English Art of the Eighteenth Century (London, 1975).

Kerry Downes, Hawksmoor (1959; 2d ed., London, 1979); Kerry Downes, Vanbrugh (London, 1977); and Kerry

Levine, Neil. “Castle Howard and the Emergence of the Modern Architectural Subject.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62, no. 3 (2003): 326–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/3592518

Murray, Venetia. Castle Howard: The Life and Times of a Stately Home. 1st ed. London;New York;: Viking, 1994.

Saumarez Smith, Charles. The Building of Castle Howard. London: Faber and Faber, 1990.

“The Howard Family,” Castle Howard, Historic House North Yorkshire, accessed April 24, 2021, https://www.castlehoward.co.uk/visit-us/the-house/the-howard-family

Images

Figure 1. John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor, Castle Howard, Yorkshire, begun 1699, aerial perspective, ca.1715. From Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, vol. 3 (London, 1725)

Figure 2. Deacon, Laura. 2018.

Figure 3. Saumarez Smith, Charles. The Building of Castle Howard. 119.

Figure 4. Ibid. 133.

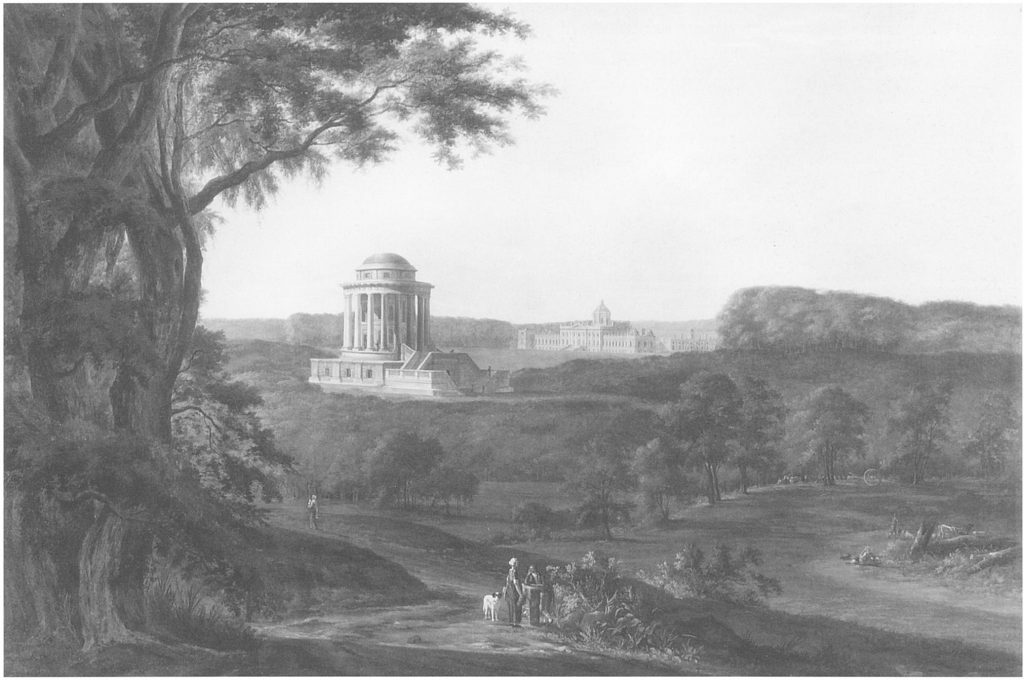

Figure 5. Hendrik de Cort, Castle Howard: Mausoleum and House, 1800

Figure 6. Levine, Neil. 340.

Figure 7. Hawksmoor, Mausoleum, Castle Howard, 1722-45 (bastioned walls around the base and stairway by Daniel Garrett, 1738-45)

Figure 8. Levine, Neil. 342.