William Marlow, View of the Wilderness at Kew, 1763, Watercolour on paper, Coutesy The Metropolitain Museum of Art.

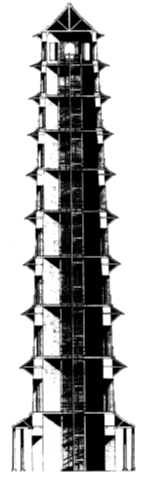

The Great Pagoda at the Royal Botanic Kew Gardens was completed in 1762. Located outside of London, the Gardens were a project of Frederick, Prince of Wales and Dowager Princess of Wales, Augusta, who between 1731 and 1750 acquired the land which would be developed into this pleasure garden[1] (Figure 1). Contained within the Gardens were artificial lakes, flower gardens, replica Greco-Roman temples, a Menagerie, various statues, a mosque; along with, three Chinese-inspired projects: the pavilion at the Menagerie, House of Confucius, and the Great Pagoda[2]. The Great Pagoda (Figure 2), along with much of Garden, was designed by the prominent 18th-century architect Sir William Chambers. Widely acknowledged as the centrepiece of the Gardens, the Pagoda was an octagonal brick building that rose forty-eight meters tall, comprising ten-story, and was ornamented with colourfully varnished iron tiling and eighty glass-covered wooden dragons that shimmered from the eaves[3] (Figure 3). The building, adapted two decades after its completion, and then subsequently in the late nineteenth century, and restored most recently by the Historic Royal Palaces society, in 2018, remains at the Gardens today, in only a likeness of its original design[4].

Figure 1. Plan of the Royal Gardens and Par at Richmond in 1754 in Surprising historical facts about Key Gardens

Figure 2. Photograph of The Great Pagoda, at Kew Gardens, taken by EBS, 2018

Figure 3. one of eighty restored wooden dragons replaced on the Pegoda during 2017-2018 restoration. Stuart Axe, Flickr, 2018

The construction of the Pagoda, along with the other Chinese-inspired structures at Kew, was part of broader cultural, commercial, and aesthetic trends throughout Britain. Venessa Alayrac-Fielding, among others, has articulated, the impact of the East India Companies’ commercial expansion into China and the influx of Chinese cultural objects into England’s ports, markets, and homes[5]. Throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth century, the increasing presence of Chinese goods, motifs, and materials inspired England’s popular fascination with the Chinese civilization[6].

Early contact between Europeans and Chinese dates back to the early seventeenth century, during which time missionary expeditions served as a connection and medium for trans-cultural exchanges of language, arts, and other cultural objects[7]. Jesuits missionary accounts of the Chinese civilization took a pseudo-universalist perspective on the cultural expressions found therein, thinking ‘…beyond Greco-Roman classicism’ these early reports extended an ‘inclusiveness’ of cultural legitimacy ‘not extended to the architecture of numerous other cultures viewed by Europeans[8]. However as European colonialism in Asia advanced, this perception of China was replaced with an image of Chinese culture and subjectivity that was intertwined with the racialized concepts of Orientalism, an ‘unfathomable’ and sublime orient, that expressed the discomfort implicit in European empires failure to establish favourable commercial arraignments, never mind colonize, the far East[9]. In this context, luxury imports such as Chinese porcelain, silks, decorations, became fashionable statements about their proprietors’ class as well as symbolic emblems of Britain’s imperial national identity. The rise in popularity of Chinese goods in England inspired shifts in taste and a pronounced impact on manufacturing both internationally and domestically: the emergence of Chinoiserie[10].

Chinoiserie, the imitation of motifs and techniques of Chinese aesthetics in European art, furniture and architecture, emerged as a means to exhibit the novelty that the Chinese represented to Britain; while also, expressing and maintaining a favourable image of imperial ideology within Britain. As Stacy Sloboda and others have demonstrated, imperial commercial activity in Asia was a necessary precondition for the European market for Chinese cultural artifacts. The consumption of the Chinoiserie, therefore, materialized the notion of empire within everyday life. Though, as Porter aptly argues, this sense of visualizing empire was precarious to sustain given the upper hand the Chinese empire maintained in foreign relations before the Anglo-Sino wars [11]. The status of the Chinoiserie was therefore variable throughout its history in British culture. Its value as an aesthetic became simultaneously bound up in ideas of racialized otherness, classicism and proper British taste, as well as an increasing class and gender, divide within 18th century England[12] (Figure 4). By the height of Chinoiserie’s popularity in Britain, there was an increasing linkage between objects and style of the orient and the sublime, the irrational, and the feminine. The ‘craving for Chinese porcelain, among other objects, was linked to the extravagances associated with both woman’s leisure and taste as well as a growing mercantile class, burgeoning from the expanding trade opportunities[13].

Figure 4. ‘Chinoiserie’ scenes on tin-glazed tile from Bristol c. 1725-50, depicting exaggerated Chinese motifs.

Concurrent instances of the immense popularity and disdain for Chinoiserie is attributable to this intersection of an emerging consumer society – the ‘nouveau riche’ of Robert Lloyd’s poetry — negotiating an aesthetic through the subversion of an elite and established classists milieu; modern aesthetic conceptions of sensuality and exoticism; and the expression of nationalistic sentiment through the ownership and dominion of foreign commodities[14]

In the case of the Chinoiserie architecture of 18th century British, there was a deliberate effort, regarding the phenomenon’s most notable instantiations, to distance the projects from the public perception of the chinoiserie being primarily about frivolous and decorative ornamentation[15]. The interior and exterior spaces created in the Chinoiserie are principal sites of ‘critical ornamentation’, as Sloboda aptly articulates in Chinoiserie, therein defining spaces such as Admiral Anson’s Garden at Shugborough Hall (Figure 5) and Kew Gardens as cultural agents, wherein imperiality and extractive commercial enterprise become embedded in the landscape [16]. In the case of Anson’s Garden and hall at Shugborough, the folly of the bridge enacts the conceptual tour to the Far East and the Chinoiserie interiors and decoration of porcelain teacups and cabinets, perform the imaginary of imperial conquest by framing Chinese artifacts as trophies[17]. Another most famous case of this category of Chinoiserie is the miniature sculptural Pagodas housed at the Royal Pavilion (Figure 6), wherein a similar effect of that at Shugborough is achieved by inverting the scaler relationship of the artifacts, thereby rendering the cultural significance of the pagoda inert and metaphorically brings the culture into the domain of the British empire [18] . The spatial practice of Chinoiserie gardens and their architectural follies conveys the power and wealth of their Royal proprietors, and by direction association, the British Empire.

Figure 5. The Chinese House at Shugborough. The Royal Oak Foundation, 2017

The use of architectural follies as a technology of expressing sovereign power and regimes of domination, in the case of the Chinoiserie, required an exactness of expression to legitimate the narrative of authority over foreignness[19]. The need for authenticity in representation, and tacitly the validity of knowledge about and power over the subject, was arguable exacerbating by the ongoing debates over the value of Chinoiserie in contemporary British aesthetics and culture. The fact that imitations of Chinese aesthetics were, by the mid 18th century, understood in part as a frivolous, decorative, and ‘mute ornamental style’[20], necessitated that designers of the momentous chinoiserie gardens and follies establish authenticity of knowledge over Chinese garden design and therefore the legitimacy and earnestness of their projects. Herein, authenticity is chiefly a product of the experience of China, and Chinese gardens and architecture specifically. Due to the limitation of access to China, beyond the sanctioned areas of Canton[21] there existed few observers with direct experience of China. Designers of chinoiserie in Britain, including Chambers, endeavoured to verify their project’s authenticity principle through claims of access to individuals who had been aboard ships that visited the Port at Canton[22]. Drawing from Susan Stewart’s idea of the souvenir, McDowall identifies the analogous effect of this authenticity through experience paradigm, with the function of the tourist’s souvenir to appropriate, and thereby ‘tame’ an experienced place and people.[23]

Figure 6. Anonymous, Pagoda, c.1800-1803, porcelain, bone china, scagliola, and ormolu. 581x104x87 cm. Image courtesy Royal Collection Trust

Chambers, in efforts to legitimate the works at Kew, engaged in numerous publications aimed at substantiating the breadth of his knowledge regarding Chinese Gardens. Yu Liu demonstrates in their research on Chambers’ writings that the architect’s claim to first-hand experience and knowledge of Chinese gardens, via his two brief visits to Canton under the Swedish East India Company, was quite limited[24]. Liu convincingly presents that to manifest a reputation as an authority regarding Chinese design, and grant legitimacy to his architectural treatises, drawings, and projects, Chambers embellished the breadth of his experience and fabricated Chinese sources. Instead, Chambers’ knowledge relied heavily on Western reportage, namely that of the Jesuit missionary Jean-Denis Attiret, who in 1743 wrote and drew sketches of the Yuan-Ming-Yuan complexes in present-day Beijing[25].

Though Attiret’s resources expressed the quasi-universalist Jesuit-derived image of China, with an ambiance towards the evaluation of foreign aesthetics, the nascent racial coding of Chinese devices and the idea of exoticism is thoroughly present in Chambers writings on Chinese Gardens during and following his time spend designing the Great Pagoda and Kew [26]. Although as evidence by his 1757 publication of Designs of Chinese Buildings, Chambers was fixed on issues of cultural authenticity, aiming to, in his words: ‘put a stop to the extravagancies that daily appear under the name of Chinese’[27]; his writing herein, as well as in subsequent publications in the 1772 Dissertation on Oriental Gardening, offer a casual and highly fantastical treatment of Chinese gardens within his tripartite vision of typologies[28]. Throughout Chambers’ writing, the scholastic and serious contemplative purpose of Chinese gardens is omitted and replaced by the highly orientalist and exoticized image of sensual spaces[29]. Correspondingly, the Pagoda at Kew indeed lacks the cultural authenticity of the Chinese form, falling within the generalized European trend of a cavalier misappropriation of far Eastern design elements and a lack of earnest study of Chinese cultural forms.

Material evidence succinctly summarized by Prosser supports the claim that Chambers’ execution of the Pagoda at Kew gave negligible consideration to the cultural meaning of Chinese gardens and their structures. For instance, Prosser identifies the highly experimental use of enamelled iron tiles as shingles and disregard for timber joisting or structural embellishments that characterize Chinese architecture, as indications of both Chamber’s lack of experience as well as his preoccupation with exploring the novelty of materials available to him[30]. Rather than being concerned with accurate representations of Chinese garden design, much of Chambers’ work resembles scenes of architecture produced in 1665 within the Dutch trade attaché, Johan Nieuhof, treaties – a source which had been augmented to resemble rectilinear forms associated with West cultural heritages and contained structural information that was inconsistent with Chinese building practices, notably the even-numbered floors in pagoda building[31] (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Chambers, 1763, a cross-section of the Pagoda from an engraved plate, Gardens and Building at Kew, Courtesy Tim Knox

Despite Chamber’s efforts to establish the legitimacy of his knowledge and expertise on Chinese gardens and buildings, there is substantial evidence supporting that his work at Kew was largely based on biased and distorted second-hand reports of Chinese architecture. Despite this lack of cultural authenticity, the great pagoda at Kew nevertheless offers precedent as an articulation of British imperialism, in so far as the project projects images of otherness within the British landscape[32]. The deployment of Chinese styled buildings within Kew in a haphazardly appropriated way aligns with the idea of the chinoiserie being about novelty, curiosities, and the ‘unfathomable other’; which, Porter argues, is at the core of the colonial projects requirement to trivialize the cultural authority of the foreign and deride the possibility of a legitimate foreign subjectivity through the creation of the oriental gaze[33]. Sloboda’s notion of cultural agency here lets us understanding the landscape architecture of the Chinese Garden as a site that is productive of cultural difference and othering. Tellingly, the height of the Chinoiserie movement in Britain, marked by the creation of the Great Pagoda at Kew, was quickly followed by a decline in British-Chinese relations, the first Opium Wars (1839-1842), the subjugation of China to British colonization, and the emergence of the idea of an inferior Chinese civilization within English cultural expression[34]

[1] See: Liu, Y. (2018). The Real vs the Imaginary: Sir William Chambers on the Chinese Garden

[2] Ibid, pp 678-681

[3] Knox, T. (1994, July). The great Pagoda at Kew. History Today, p.26

[4] Prosser, L. (2019). The Great Pagoda at Kew: Colour and Technical Innovation in Chinoiserie Architecture. P. 70

[5] Alayrac‐Fielding, V. (2009). ‘Frailty, thy name is China’: Women, chinoiserie and the threat of low culture in eighteenth‐century England. And see: Stacey Sloboda, 2014 for general commercial trends in the Chinoiserie style, as well as Porter, 2002

[6] Porter, D. L. (2002). Monstrous Beauty. pp. 369-400; also see: Sloboda, S. (2014). Chinoiserie.

[7] Blakley, K. (2018). Domesticating Orientalism.

[8] Godel, A. (2020). From “Terrestrial Paradise” to “Deary Waste.” In Race and Modern Architecture. pp. 80–85

[9] Ibid, 91-93

[10] Sloboda, S. (2014). Chinoiserie. Pp .45-88; also see: Porter, D. L. (2002). Monstrous Beauty.

[11] See Porter (2002). Pp 400-403

[12] Regarding racial and pre-racial thought on Chinese aesthetics see Godel (2020) in Terrestrial Paradise to Dreary Waste’; on the subject of Chinoiserie and Classicism in 18th century Britain see Porter’s (2002) publication Monstrous Beauty’ also see Prosser (2017); and on gendered consumption and trade of Chinoiserie see Jenkins (2009) Nature to Advance Drest: Chinoiserie, aesthetic form, and the poetry of subjectivity in Pope and Swift.

[13] See James Arbuckle’s 1729 letters in Alayrac-Feilding (2009) Frailty, thy name is China pp 660-668.

[14] Porter, D. L. (2002). Monstrous Beauty. p.407, Sloboda (2014) account of Chinoiserie as flexible social indicators, and her reference to 1757 classists commentator Shaftesbury’s (1757) poem The Crit Country Box

[15] Sloboda, S. (2014). Chinoiserie. p. 06

[16] Ibid, p170-179

[17] Ibid, p.177

[18] Blakley, K. (2018). Domesticating Orientalism. p.216

[19] Saussy, H. (2007). Empires, Gardens, Collections: How Each Explains the Others. Pp148-149

[20] See: Sloboda (2014), p.6

[21] Blakley (2018) Domesticating Orientalism, pp. 207-208

[22] See: McDowall (2016), Imperial Plots?,

[23] Ibid. p.26

[24] Liu, Y. (2018). The Real vs the Imaginary. Pp.676-677

[25] Ibid

[26] Godel (2020) 79-92

[27] Chambers (1757), preface

[28] Godel (2020). p.89; also see Lui (2018) for detailed analysis of Chambers experience.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Prosser (2019) pp. 78-81

[31] See: Prosser (2019); and Godel (2020). Pp.80-85

[32] See: final chapter in Sloboda (2020)

[33] Porter (2002), pp.400-407

[34] Godel (2020), From Terrestrial Paradise to Dreary Waste, pp 92-95

Sources:

Alayrac‐Fielding, V. (2009). ‘Frailty, thy name is China’: Women, chinoiserie and the threat of low culture in eighteenth‐century England. Women’s History Review, 18(4), 659–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612020903112398 Blakley, K. (2018). Domesticating Orientalism: Chinoiserie and the Pagodas of the Royal Pavilion, Brighton. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 18(2), 206-223,290. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1080/14434318.2018.1519873 Chambers, W. (1763). Plans, elevations, sections, and perspective views of the gardens and buildings at Kew, in Surry … London : Printed by J. Habaerkorn; pub. for the author [etc.]. http://archive.org/details/planselevationss0000cham Chambers, W., Bartolozzi, F., Cipriani, G. B., & Griffin, W. (1773). A dissertation on oriental gardening. London : Printed by W. Griffin, printer to the Royal Academy : sold by him in Catherine-street, and by T. Davies … : also by J. Dodsley … Wilson and Nicoll … J. Walter … and P. Elmsley … http://archive.org/details/dissertationonor00cham Chambers, W., Fourdrinier, P., Grignion, C., & Sandby, P. (1757). Designs of Chinese buildings, furniture, dresses, machines, and utensils. London : Published for the author, and sold by him …, also by Mess. Dodsley …, Mess. Wilson and Durham …, Mr. A. Millar …, and Mr. R. Willock … http://archive.org/details/DesignsChineseb00ChamFull Text PDF. (n.d.-a). Retrieved April 23, 2021, from https://media.proquest.com/media/hms/PFT/1/ROtG8?cit%3Aauth=Blakley%2C+Kara&cit%3Atitle=Domesticating+Orientalism%3A+Chinoiserie+and+the+Pagodas+of+the+Royal+Pavilion%2C+Brighton&cit%3Apub=Australian+and+New+Zealand+Journal+of+Art&cit%3Avol=18&cit%3Aiss=2&cit%3Apg=206&cit%3Adate=2018&ic=true&cit%3Aprod=Arts+Premium+Collection&_a=ChgyMDIxMDQyMzE4NTY1Mzk2NzoyMTkxOTESBjEwNTM5OBoKT05FX1NFQVJDSCIOMTI5LjIxNS4xNy4xODgqBjk0NjM1ODIKMjE3MDgzMTE3NToNRG9jdW1lbnRJbWFnZUIBMFIGT25saW5lWgJGVGIDUEZUagoyMDE4LzAxLzAxcgoyMDE4LzEyLzMxegCCATJQLTEwMDAyNzctMTA2NzMtQ1VTVE9NRVItMTAwMDAyMzUvMTAwMDAxODAtNTI3MDUzM5IBBk9ubGluZcoBc01vemlsbGEvNS4wIChXaW5kb3dzIE5UIDEwLjA7IFdpbjY0OyB4NjQpIEFwcGxlV2ViS2l0LzUzNy4zNiAoS0hUTUwsIGxpa2UgR2Vja28pIENocm9tZS84OS4wLjQzODkuMTI4IFNhZmFyaS81MzcuMzbSARJTY2hvbGFybHkgSm91cm5hbHOaAgdQcmVQYWlkqgIlT1M6RU1TLURvd25sb2FkUGRmLWdldE1lZGlhVXJsRm9ySXRlbcoCCkNvbW1lbnRhcnnSAgFZ4gIBTvICAPoCAU6CAwNXZWKKAxxDSUQ6MjAyMTA0MjMxODU2NTM5NjM6NjYzNTY4&_s=mSl%2BzJWMlvFfp7HlXbIAxhrQIqw%3DFull Text PDF. (n.d.-b). Retrieved April 25, 2021, from https://media.proquest.com/media/pq/classic/doc/1660432/fmt/pi/rep/NONE?cit%3Aauth=Knox%2C+Tim&cit%3Atitle=The+great+Pagoda+at+Kew&cit%3Apub=History+Today&cit%3Avol=44&cit%3Aiss=7&cit%3Apg=22&cit%3Adate=Jul+1994&ic=true&cit%3Aprod=ProQuest&_a=ChgyMDIxMDQyNTIyNDczNDYzODo4NzI3MDMSBjEwNTM5OBoKT05FX1NFQVJDSCIOMTI5LjIxNS4xNy4xODgqBTQyNDU0MgkyMDI4MTAwNzE6DURvY3VtZW50SW1hZ2VCATBSBk9ubGluZVoCRlRiA1BGVGoKMTk5NC8wNy8wMXIKMTk5NC8wNy8zMXoAggEyUC0xMDAwMjc3LTEwNjczLUNVU1RPTUVSLTEwMDAwMjM1LzEwMDAwMTgwLTUyNzA1MzOSAQZPbmxpbmXKAXNNb3ppbGxhLzUuMCAoV2luZG93cyBOVCAxMC4wOyBXaW42NDsgeDY0KSBBcHBsZVdlYktpdC81MzcuMzYgKEtIVE1MLCBsaWtlIEdlY2tvKSBDaHJvbWUvODkuMC40Mzg5LjEyOCBTYWZhcmkvNTM3LjM20gEJTWFnYXppbmVzmgIHUHJlUGFpZKoCJU9TOkVNUy1Eb3dubG9hZFBkZi1nZXRNZWRpYVVybEZvckl0ZW3KAgdGZWF0dXJl0gIBWeICAU7yAgD6AgFOggMDV2ViigMcQ0lEOjIwMjEwNDI1MjI0NzM0NjM0OjYyMzk5MQ%3D%3D&_s=ZGsoAKPk8TSEngvzt3BYw7evjr0%3D Godel, A. (2020). From “Terrestrial Paradise” to “Deary Waste.” In Race and Modern Architecture (pp. 70–98). Jenkins, E. Z. (2009). “Nature to Advantage Drest”: Chinoiserie, Aesthetic Form, and the Poetry of Subjectivity in Pope and Swift. Eighteenth – Century Studies, 43(1), 75–94. Knox, T. (1994, July). The great Pagoda at Kew. History Today, 44(7), 22. Liu, Y. (2018). The Real vs the Imaginary: Sir William Chambers on the Chinese Garden. The European Legacy. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/doi/abs/10.1080/10848770.2018.1470382 Lloyd, R. (1757). The Crits Country Box. https://www.eighteenthcenturypoetry.org/works/o5089-w0090.shtml McDowall, S. (2016). Imperial Plots? Shugborough, Chinoiserie and Imperial Ideology in Eighteenth-Century British Gardens. Cultural and Social History. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/doi/abs/10.1080/14780038.2016.1237450 Pagodas. (1900, November 10). Scientific American (1845-1908), Vol. LXXXIII.(No. 19.), 299. Porter, D. L. (2002). Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 35(3), 395–411. Prosser, L. (2019). The Great Pagoda at Kew: Colour and Technical Innovation in Chinoiserie Architecture. Architectural History. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1017/arh.2019.3 Saussy, H. (2007). Empires, Gardens, Collections: How Each Explains the Others. In Critical Zone 2: A Forum of Chinese and Western Knowledge (pp. 147–166). Hong Kong University Press. Sloboda, S. (2014). Chinoiserie: Commerce and critical ornament in eighteenth-century Britain. University Press. Snapshot. (n.d.-a). Retrieved April 23, 2021, from https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/doi/full/10.1080/14780038.2016.1237450Snapshot. (n.d.-b). Retrieved April 25, 2021, from https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/doi/full/10.1080/10848770.2018.1470382Suggested in a preliminary version of this article, the repeated insistence on cultural authenticity that surrounds the . (n.d.). That the intense craze for chinoiserie in the garden had faded so significantly by the late 1750s problematizes any read. (n.d.). The century between 1750 and 1850 witnessed a profound deterioration in the relationship between China and Britain, with. (n.d.). The taste for things Chinese had been fostered by the long established trade connections between China and Europe. Indee. (n.d.).