While once commonplace in the American landscape, mental asylums are often seen as obsolete relics of an antiquated form of psychiatry. The typology of a stately, manicured hospital for the “insane” emerged in the latter half of the nineteenth century as representations of a newfangled, “moral” and romanticized view of treating mental illness.1 This relatively progressive understanding of therapy corresponded with another major transition in the social fabric of the United States: the abolishment of slavery and the integration of freed African Americans. As a result, asylum architecture became an expression of its historical context, with progressive ideas finding their footing in a society built upon an engrained sense of colonialism and racism that permitted slavery for decades. In order to explore this topic, I will focus on St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, a Washington asylum founded and designed in 1855 under superintendent Dr. Charles H. Nichols with the help of architect Thomas U. Walter.2 St. Elizabeth’s was the first federally funded mental hospital in the United States, and was designed to be a model and leader of progressivism in its field. 3As one of the first asylums to accept all races, it was inevitable that the design would reflect the social context, leaving St. Elizabeth’s as an architectural construction of the transition between two colonialist treatments of African Americans: slavery and segregation. Despite being proclaimed as a progressive model of inclusion, the design of St. Elizabeth’s landscaping, layout, and hospital wards was an extension of colonialist and supremacist ideologies, representing an era of white doctors deciding and designing the sanity of African Americans.

1. D’Antonio, Patricia. “History of Psychiatric Hospitals.” • Nursing, History, and Health Care • Penn Nursing. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/nhhc/nurses-institutions-caring/history-of-psychiatric-hospitals/.

2. Otto, Thomas. “St. Elizabeth’s Hospital: A History.” United States General Services Administration, 2007. https://dcpreservation-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/0-COMPLETE-St.-Elizabeths-Hospital-A-History.pdf.

3. Summers, Martin. Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. University Press Scholarship Online, 2019. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190852641.001.0001.

Landscape

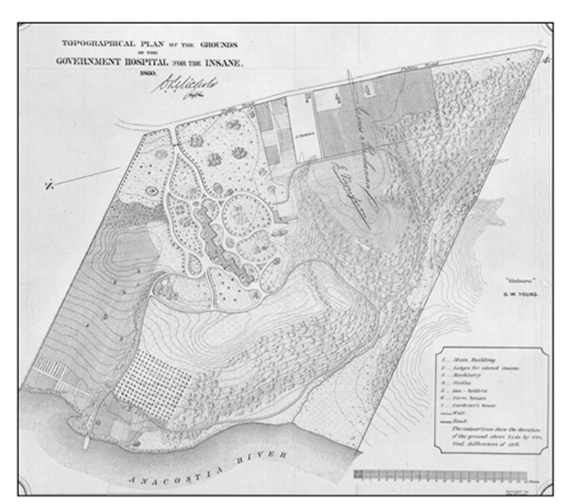

St. Elizabeth’s Hospital was constructed on a wooded plateau overlooking Washington’s Anacostia River beginning in 1852.3 Throughout the first years, the ridge was perfectly outfitted to suit the needs of the hospital, with patchwork orchards and farmlands surrounding a sprawling lawn dotted with a variety of trees and shrubs (see Figure 1). The understanding of mental illness and psychology at the time of St. Elizabeth’s design and construction followed the “belief that mental illness stemmed from situations in a person’s environment”.2 As a result, the siting of the asylum was crucial in the hospital’s perceived success, and required a location that featured “convenient pleasure-grounds” with picturesque views of the landscape.1 Superintendent and designer Nichols believed that nature distracted the “diseased mind from its delusions”, and designed the grounds to include walkways and parterres surrounded by greenery and flowers in a park-like design.2

Government Hospital for the Insane Saint Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, D.C. Topographical plan of the grounds. Washington D.C, 1860. , Copied Later. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016652052/.

However, Nichols’ initial design for the landscape at St. Elizabeth’s did not extend to all of the hospital’s patients. While white patients were permitted to wander the peaceful grounds, the “coloured” patients were merely provided with segregated “airing yards”, wedged between the lodges and livestock stables.4 Despite designing with an understanding of the therapeutic benefits of picturesque views and extensive greenery for the “strolling invalid” 2, Nichols omitted non-white people from his landscape and the associated narrative. This design decision demonstrates Nichols’ racist perception that the minds of non-white patients were less worthy of improvement, revoking the right to participate in the therapeutic space he had designed, and subsequently subjecting them to less effective treatment. Nichols, despite his insistence on progressivism, was designing under the effects of years of racist colonialism. The minds of African Americans in his asylum were perhaps not seen as property, but they were still viewed as inherently different and undeserving of the same regimen. Consequently, racist preconceptions of the time and the ensuing architectural designs compromised African American patient’s health and sanity.

4. Novicoff, Sarah. “The Establishment and Early Years of the Government Hospital for the Insane.” Penn History Review, 5, 25, no. 1 (2018).

Thomasp94. St Elizabeth WestCampus. March 15, 2010. Asylum Projects. http://asylumprojects.org/index.php?title=File:St_Elizabeth_WestCampus.jpg.

Layout

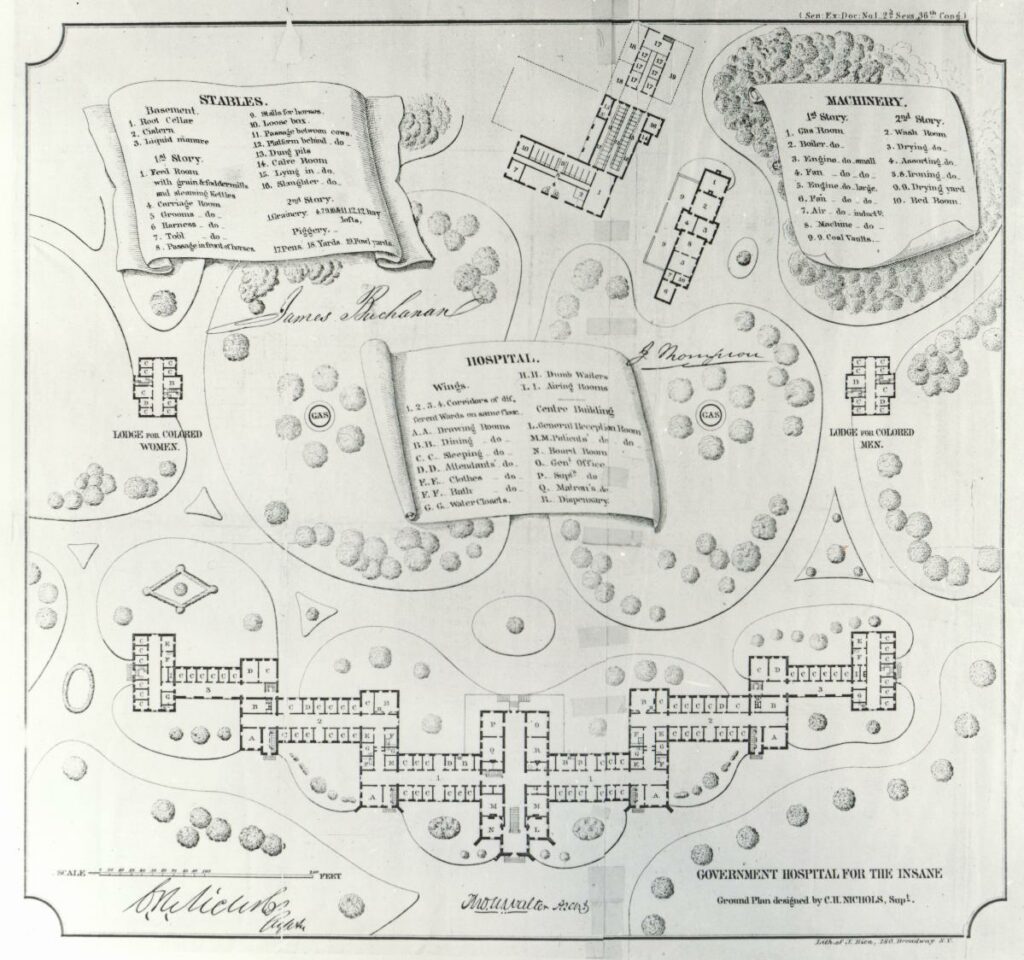

Nichols, Charles H, John M Coyle, Thomas Ustick Walter, and United States Congress. Senate. Maps of Saint Elizabeths Hospital, Washington D.C. [Washington: U.S. Senate, ?, 1860] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/88693084/.

In addition to being erased from the landscape design, perhaps the most direct result of St. Elizabeth’s colonialist design can be seen directly highlighted in the hospital’s plan. Figure 3 illustrates the orientation, placement, and overall layout of St. Elizabeth’s buildings, and most notably depicts the segregated architectural conditions for non-white patients. The central building stands out in the plan, sprawling and intricate. Comparatively, just above the central building sits two “lodges for coloured” patients, split by gender. When designing for a racially heterogeneous hospital, Nichols specified that the solution for segregation was found in the “cottage system”, where non-white patients were housed “not more than 200 nor more than 400 feet” from the central building.3,5 This design was applauded by many for its progressivism, with the following superintendent, Godding, stating:

“More than thirty years ago this departure in the direction of distinct provision, for different classes, had here its origin in the far-sighted wisdom of the then superintendent who built his heart into his work and so built nothing unworthily, and made here the first distinct, detached building for the colored insane in America, thereby placing his hospital provision outside of the [AMSAII] propositions by placing it twenty-five years ahead of his time and abreast of the requirements of to-day.”3

This statement clearly reiterates that the perceived progressivism in St. Elizabeth’s design is retrospectively not only a reflection of an era still deeply entrenched in colonial thinking, but a designed, active participant. Banished from the traditional center of therapy into designed spaces of exclusion masquerading as progressivism, the supposed haven-like asylum seemed no different from Mount Vernon, Monticello, or other plantations of the south where the slave quarters were removed from the master’s lodge.5 Black patients were only provisionally accepted; their psychiatric care was jeopardized through medical protocol and architectural design both invested in colonialist ideologies.

5. Anthony, Carl. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters: Part I, Prelude to New World Architecture.” Landscape 20, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 8-19

Building

Walter, Thomas U. St. Elizabeth’s Hospital (Originally Hospital for the Insane of the Army and Navy and District of Columbia). 1852.

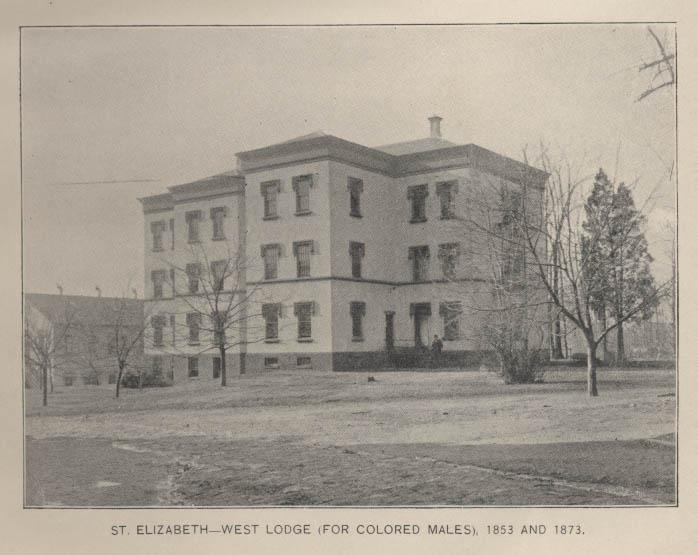

While Nichols’ experience in the field allowed him to design the grounds and general layout at St. Elizabeth’s, it was architect Walter who was charged with creating a cohesive exterior and finessing the plans.6 For the central building, Walter chose the fortress-like design of the collegiate gothic style, a gothic Revival.2 This façade was simultaneously professional, grand, and relatively inexpensive. Meanwhile, in another instance of architectural exclusion, the “coloured” lodges were described as plain in ornamentation in order to be more cost effective. As mental illnesses were seen as products of unhealthy environments, many asylums of the time invoked the design advice of the influential physician Thomas Kirkbride, who even wrote a book carefully describing the ideal layout of an asylum.6 In the Kirkbride plan, the central tower would gather all patients, who would then be segregated in two wings by gender, and again by condition. Each ward was set back, allowing for increased ventilation, sunlight, in each.2 The linear plan with wide hallways allowed every room to have a window, permitting patients to reap the therapeutic benefits of admiring the picturesque views of the river to the north and farmlands to the south. 6However, this integration of design and therapy was not extended to the non-white patients. The plan for the “coloured” lodges was a simple square, omitting non-white patients from the perceived treatment associated in the design of the Kirkbride plan. Without the linear design, views of nature were not prioritized, rooms were packed full of beds, and ventilation was decreased.4 Notably, many doctors stressed the importance of fresh air, but the space allotted for African Americans at St. Elizabeth’s was not designed to harness proper ventilation, and as a result, the patients carried a “greater olfactory burden”.4 Additionally, the Kirkbride plan was praised for segregating patients so a “melancholic” would be distanced from the outbursts of an “epileptic”. Conversely, the square plan symbolized a disregard for the atmosphere and serenity in the coloured wards, as all patients, regardless of condition or socioeconomic standing, were banished to the same rooms in the square lodge.4 In designing this way, Nichols and Walter effectively disadvantaged the non-white patients in their treatment and experience at St. Elizabeth’s, from the overall landscape to the finest architectural details.

6. Yanni, Carla. “The Linear Plan for Insane Asylums in the United States before 1866.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62, no. 1 (2003): 24–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/3655082.

St. Elizabeth – West Lodge (for Colored Males) 1853 and 1873. Museum of Disability. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.museumofdisability.org/assets/1855a.jpg.

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Showing Crowded Condition in Colored Dormitory, 1925. National Archives Catalog. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5664745.

In conclusion, at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, a history of colonialist, racist treatment towards people of colour pervaded multiple scales of design choices. These ideologies were expressed as exclusionary architecture, further allowing the white doctors to control the mental state of their non-white patients. While the asylum can be commended for being the third asylum in the United States to accept more than one race, the landscaping, layout and buildings were all specifically designed to disadvantage African American patients. Fortunately, the hospital gradually evolved into a more inclusive space during the decades following its design and construction. Activism by organizations like the NAACP encouraged St. Elizabeth’s to hire African American nurses and doctors, which in turn led to architectural changes such as the razing of the “coloured lodges” in the 1960s.2 St. Elizabeth’s Hospital exists today as an example of colonial, racist architectural designs, and the extremely harmful medical and social consequences. Nevertheless, the asylum also exemplifies the effort to overcome colonialist design and create spaces which are truly therapeutic for everyone.

Bibliography

Anthony, Carl. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters: Part I, Prelude to New World Architecture.” Landscape 20, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 8-19

D’Antonio, Patricia. “History of Psychiatric Hospitals.” • Nursing, History, and Health Care • Penn Nursing. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/nhhc/nurses-institutions-caring/history-of-psychiatric-hospitals/.

Novicoff, Sarah. “The Establishment and Early Years of the Government Hospital for the Insane.” Penn History Review, 5, 25, no. 1 (2018).

Otto, Thomas. “St. Elizabeth’s Hospital: A History.” United States General Services Administration, 2007. https://dcpreservation-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/0-COMPLETE-St.-Elizabeths-Hospital-A-History.pdf.

Summers, Martin. Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. University Press Scholarship Online, 2019. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190852641.001.0001.

Yanni, Carla. “The Linear Plan for Insane Asylums in the United States before 1866.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62, no. 1 (2003): 24–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/3655082.