A Glance at Belgium and the Misconstrued Perception of its Colonial Past

The Royal Museum for Central Africa, currently referred to as the AfricaMuseum, located in Tervuren, Belgium is a colonial museum that was founded by King Leopold II at the very end of the 19th century.[1] The origin of the museum “dates back to the Brussels International Exposition of 1897,” and consisted of “naturalised animals, geological samples, commodities, Congolese ethnographic and artistic objects and art objects created in Belgium.”[2] These collections were gathered and appropriated from the colonies of Belgium, Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and beyond.[3] The RMCA stands, to this date, as a leading symbol of Belgium’s imperial dominance and “best exemplifies Belgium’s ambiguous relation to its colonial past.”[4] The museum, through its name, claims to pose as an embodiment of Central Africa, however, it was founded, developed, curated and manipulated by Belgians. While it was intended to pose as a symbol of discovery as well as control by Leopold, the building has further embedded xenophobic and hierarchal judgements amongst its visitor as well as contributed to the concealing of Belgium’s abominable colonial history. This will be explored through the discussion of King Leopold II’s intention for the museum, the actual representations and distinctions displayed of Europeans and Africans throughout the building, as well as the lasting effects this has created and how these notions have carried through the museum to this date.

King Leopold II “appropriated Congo as his own personal colony” in 1885.[5] While he was believed by most Belgians to be a noble and civilized leader,[6] “at least four million Congolese died under […his] rule from violence, disease and starvation.”[7] Leopold curated an exploitative and gruesome system that was motivated purely by societal advancement and greed during the rubber trade.[8] While Leopold exerted his dominance amongst the Congo, he sought out an institution in Belgium to pose as an “ideological tool aimed at countering the growing criticism that his activities (the brutal and bloody repression performed by his subordinates) in the Congo were drawing internationally.”[9] He saw the museum as a “propaganda tool”[10] for his colonial endeavours of gaining imperial omnipotence and appreciation. As Belgium was a newly found and young nation state during this time period, the application of a “colonial museum was intended also to ‘educate’ the Belgian public as to who they really were in contradistinction to the uncivilized Congolese ‘tribes’.”[11] Hence, it is made apparent through Leopold’s intentions that the creation of the museum involved impure and bigoted motives.

These ultimate motives are heavily apparent through the techniques of representation displayed throughout the museum. The museum fixates on the need to civilize and control the people of the Congo as they were foreign, unfamiliar, and did not abide by European practices. It was intended to leave the visitor with the understanding that Belgium colonized the Congo in order to abolish slavery and shed the light of civilization onto a land of “chaos, savagery, [and] injustice.”[12] Belgium hoped to exert control while ingraining that this exertion was necessary and vital in order to save the ‘uncivilized’ and ‘inhumane’ people. A guide at the museum read the following:

“On the hundreds of thousands of square kilometers that constituted mysterious Africa, nothing existed that could resemble civilization. […] Central Africa is not mysterious anymore, it is covered by roads, railroads, telegraphic communications, there are cities, justice is reigning, war between tribes has disappeared, the slave trade has been extirpated from the territory, hundreds of factories exploit the wealth of the forests and give a living to thousands of our compatriots. [. . .] A hundred and fifty thousand cannibals have been subdued by the cross, they speak like us, think like us and adore the same God as we do! No colonizing nation of Africa, not even the ones that were established on the land that they now dominate for more than a hundred years, can present as considerable results as the ones we have obtained among our indigenes. That is all this section wants to explain to the visitors.”[13]

This statement, in which hung for visitors of the museum to engage with, resembles the neglect as well as the confident belief that Belgium was doing good by colonizing and assimilating Africa and its people. It affirms the mindset of Europeans, believing themselves to be the leading and guiding race on Earth.

One of the most significant pieces of the original exhibition was the recreation of a mock African village. This village was located in the park of the museum where approximately 300 Congolese men, women and children were made to present their daily life tasks that would be completed back in Africa.[14] There were representations of a river village, a forest village, as well as a ‘civilized’ village in which consisted of force publique soldiers.[15] Seven Congolese people died at this exhibition due to pneumonia as well as influenza, as well as several others who passed during their voyage back to the Congo.[16] The mock village created a barrier between the European and the Congolese, white and black, human and animal. It accentuated the ideals perpetuated by the exhibition, those suggesting that the people of the Congo were foreign and objects of observation. The Congolese were dehumanized and objectified as artifacts. As the director of such a showcase, Leopold II never actually visited the Congolese villages as he was unwilling to come in contact with the villagers in fear of catching an illness .[17] This accentuates the notion that Leopold II, as well as the product of European culture, believed black people to be uncivilized as well as below the race of humans and further not a race that should even come in contact with the white population.

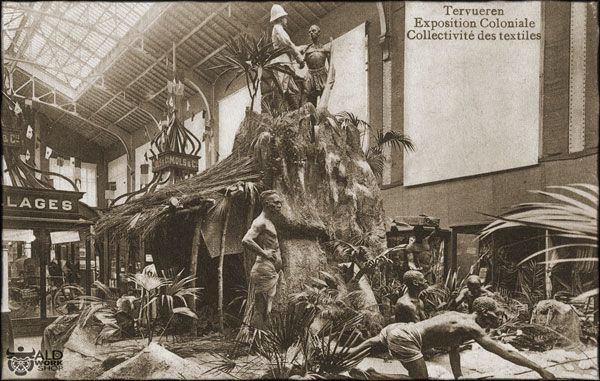

These hierarchical relations continue throughout the interior of the building. It is noticed in the displayed artifacts that “white bodies are clearly differentiated from black bodies: powerful, civilized, heroic,[…] dominant, [tall and large], versus weak, savage, anonymous, […] dominated, [and small].”[18] White bodies are acknowledged as well as referred to by name and hold the power of remembrance and significance whereas black bodies were gone unnoticed, anonymous and insignificant. All of these factors that play into the hierarchy of this museum completely disregard its purpose of showcasing the Congo in its entirety and rather illustrates the omnipotence that Belgium and its people possess. The museum became an “exhibitionary institution embodying the power ‘to show and tell,’”[19] ultimately handing power to the Belgians to create their own narrative. In this lies the controversy of museums and the power in relaying knowledge. The founder and therefore storyteller of information plays an essential role in what will be displayed and what the visitor will attain. Hence, history can be manipulated in order to favour a certain party, in this case the Belgians. Therefore, these buildings hold much power in regard to influencing the opinions as well as the perceptions of the public.

“The ambivalence in the presentation of Belgium’s relationship with the former colony ran through the whole exhibition,” and this permanent museum continues to avoid a noble and “sound account of the atrocities perpetrated by the Belgian colonizers in the Congo.”[20] The museum has since been renovated in order to abolish its negative history, however, Bockhaven states, “the renovated RMCA did not sufficiently bring to light the abuses of the colonial era” and further recommends that Belgium apologizes for its colonial past.[21] The building continues to illustrate Africa as an exotic, uncivilized, savage nation in desperate need of development and enlightenment, “with a gallery ‘In Memoriam’ of Belgium’s colonial heroes, and an entrance dome adorned with statues in praise of colonisation, it perpetuates a glorious vision of colonial times in which past and present African peoples are dehumanised.”[22] This both reflects and reinforces Belgium’s denial as well as unwillingness to admit its unsettling colonial endeavours as they continue to long hide this horrific history. To this day, “many elementary and high school teachers continue to think of the permanent exposition as being unproblematic and enthusiastically bring their students every year for field trips.”[23] Alongside this, history textbooks used by Belgian students consist of only praise and awe of Belgium’s history, with no acknowledgement of its influences on the Congo.[24] Accordingly, the RMCA itself assisted in perpetuating these problematic ideals, creating an environment of ignorance and obliviousness further allowing Belgians to admire and adorn its country’s history. Hence, the erasure of trauma in public memory seems to be the main organizing principle of the museum, leaving no apology for the exploitative and racial injustices inflicted upon the people of the Congo.

The Royal Museum for Central Africa poses as a figure of Belgium’s imperial endeavours, its conquests and supposed ‘accomplishments’. The museum, “as all of the monumental architecture in Brussels, had relegated the horrors of Leopold’s Congo to the silences of history,”[25] confirming Belgium’s neglect and disbelief in which proceeds today. “The fundamental message remains the same: when going through the revolving doors of the museum’s main entrance, one has the feeling of entering into a liminal space, frozen in time. One could almost think that the Congo is still a Belgian colony.”[26] In fact, the building proceeds to relay this message and stand tall as a proud recollection of Belgian archives. It continues to relay the presumption that the presence of Belgium was vital in Africa to civilize and bring order to the slave trade as well as to the people who were/are living in a state of ‘barbarity’.[27] In the grand scheme, museums have the power to relegate and affirm misconstrued biases as well as perpetrate corrupted perceptions of the past. “The buildings that surround us, the spaces and structures we inhabit, are all physical manifestations of the cultural beliefs and social systems that order our society.”[28] Therefore, it is essential for buildings to acknowledge their full and fledged history in order to upkeep a progressive and egalitarian surrounding society.

Notes

[1] Rahier, Jean Muteba. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition.” Research in African Literatures 34, no.1 (2003): 61.

[2] “History and Renovation.” Royal Museum for Central Africa – Tervuren – Belgium. https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history_renovation.

[3] Van Bockhaven, Vicky. “Decolonising the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium’s Second Museum Age.” Antiquity 93, vol.370 (2019): 1082.

[4] Bragard, Véronique and Stéphanie Planche. “Museum Practices and the Belgian Colonial Past: Questioning the Memories of an Ambivalent Metropole.” African and Black Diaspora 2, vol.2 (2009): 182.

[5] Joanna Kakissis, “Belgian Museum Looks At Country’s History Of Colonialism And Racism,” September 2, 2018, in Weekend Edition Sunday, produced by NPR, podcast, 7:14. https://www.npr.org/2018/09/02/644085214/belgian-museum-looks-at-countrys-history-of-colonialism-and-racism

[6] Scott, Pippa, director. 2017. King Leopold’s Ghost. Journeyman Pictures.

[7] Kakissis. “Belgian Museum Looks At Country’s History Of Colonialism And Racism.”

[8] Van Bockhaven. “Decolonising the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium’s Second Museum Age,” 1084.

[9] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 61.

[10] “History and Renovation.”

[11] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 61.

[12] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 66.

[13] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 68.

[14] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 63.

[15] Scott. King Leopold’s Ghost.

[16] Kakissis. “Belgian Museum Looks At Country’s History Of Colonialism And Racism.”

[17] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 64.

[18] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 69.

[19] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 63.

[20] Hoenig, Patrick. “Visualizing Trauma: The Belgian Museum for Central Africa and its Discontents.” Postcolonial Studies 17, vol.4 (2014): 346.

[21] Van Bockhaven. “Decolonising the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium’s Second Museum Age,” 1082.

[22] Bragard and Planche. “Museum Practices and the Belgian Colonial Past: Questioning the Memories of an Ambivalent Metropole,” 183.

[23] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 77.

[24] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 77.

[25] Hoenig. “Visualizing Trauma: The Belgian Museum for Central Africa and its Discontents,” 351.

[26] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 62.

[27] Rahier. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition,” 62.

[28] Mabel O. Wilson and Julian Rose, “Changing the Subject: Race and Public Space,” in Artforum Summer 2017, https://www.artforum.com/print/201706/changing-the-subject-race-and-public-space-68687

Bibliography

Bragard, Véronique and Stéphanie Planche. 2009. “Museum Practices and the Belgian Colonial Past: Questioning the Memories of an Ambivalent Metropole.” African and Black Diaspora 2 (2): 181-191.

“History and Renovation.” Royal Museum for Central Africa – Tervuren – Belgium. Accessed April 24, 2021. https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history_renovation.

Hoenig, Patrick. 2014. “Visualizing Trauma: The Belgian Museum for Central Africa and its Discontents.” Postcolonial Studies 17 (4): 343-366

Joanna Kakissis, “Belgian Museum Looks At Country’s History Of Colonialism And Racism,” September 2, 2018, in Weekend Edition Sunday, produced by NPR, podcast, 7:14. https://www.npr.org/2018/09/02/644085214/belgian-museum-looks-at-countrys-history-of-colonialism-and-racism

Mabel O. Wilson and Julian Rose, “Changing the Subject: Race and Public Space,” in Artforum Summer 2017. Accessed 25 April 2021. https://www.artforum.com/print/201706/changing-the-subject-race-and-public-space-68687.

Rahier, Jean Muteba. 2003. “The Ghost of Leopold II: The Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa and its Dusty Colonialist Exhibition.” Research in African Literatures 34 (1): 58-84

Scott, Pippa, director. 2017. King Leopold’s Ghost. Journeyman Pictures.

Van Bockhaven, Vicky. 2019. “Decolonising the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium’s Second Museum Age.” Antiquity 93 (370): 1082-1087.

Images

Cover Image: Belgium Tervuren Musee de Congo Belge Façade Principale. https://www.hippostcard.com/listing/belgium-tervuren-musee-de-congo-belge-facade-principale/119115

Figure 1: RMCA Tervuren. Collection RMCA Tervuren. 1897. https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history_articles/ the_human_zoo_of_tervuren_1897

Figure 2: Gautier, A. Collection MRAC Tervuren. 1897. https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history_articles/ the_human_zoo_of_tervuren_1897/

Figure 3: Colonial mission is staged as heroic adventure with Belgium playing the role of savior and civilizer of Congo, 1897.1897. http://museummenagerie.blogspot.com/2016/08/Congo-Tervuren.html

Figure 4: https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history_renovation