Order in the Halls

“Les Halles, then, is a place in restless flux, an expression of the struggle between the irrepressible, chaotic everyday and the incessant forces of centralized, authoritarian planning and capitalist control.”1

The markets of Les Halles can be traced back to the early 1100s as the “marché des Champeaux”.2 It conveniently sits on one of the few non-flooding marshes along the Seine, where goods came up by boat through Paris’ growing global trade networks.3 The centrality and visibility of the site would lend itself to be continually redesigned and rebuilt in order to showcase governmental authority. Thus, examining the series of transformations made to the site throughout the industrial period and the 19th century can reveal the “shifting notions of architectural, social and financial order” of its time.4 Processes of industrialization, including the agricultural revolution, improvements in transportation, and the rise in international trade, coincided with a population boom particular to urban centres like Paris. Subsequently, a correlating increase in demands for food and other commodities lead to greater congestion in market streets and squares. The 18th century brought with it as well a new “enlightened perception”5 of the public realm, characterized by order and cleanliness. In France, the traditional outdoor market would come to be seen as “a source of great tension”6 in the city and became a significant target of reform to abide and produce these new ideals. The once open-air market streets adopted an enclosure wherein circulation was planned and hygiene was prioritized. This new urban order allowed for stricter governmental surveillance to enforce and reinforce control over circulation and hygiene, as well as commercial activity in a time of expanding capitalist relations.7

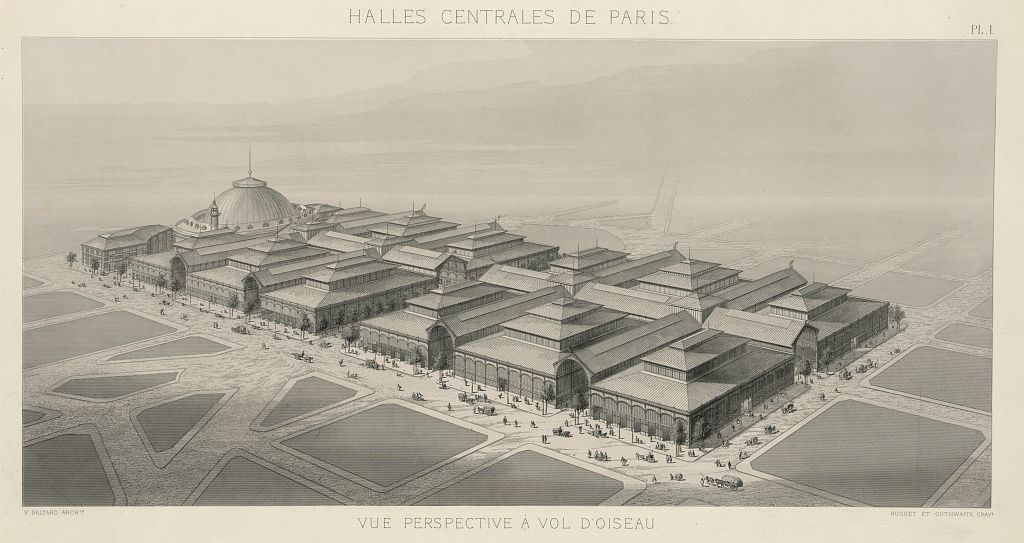

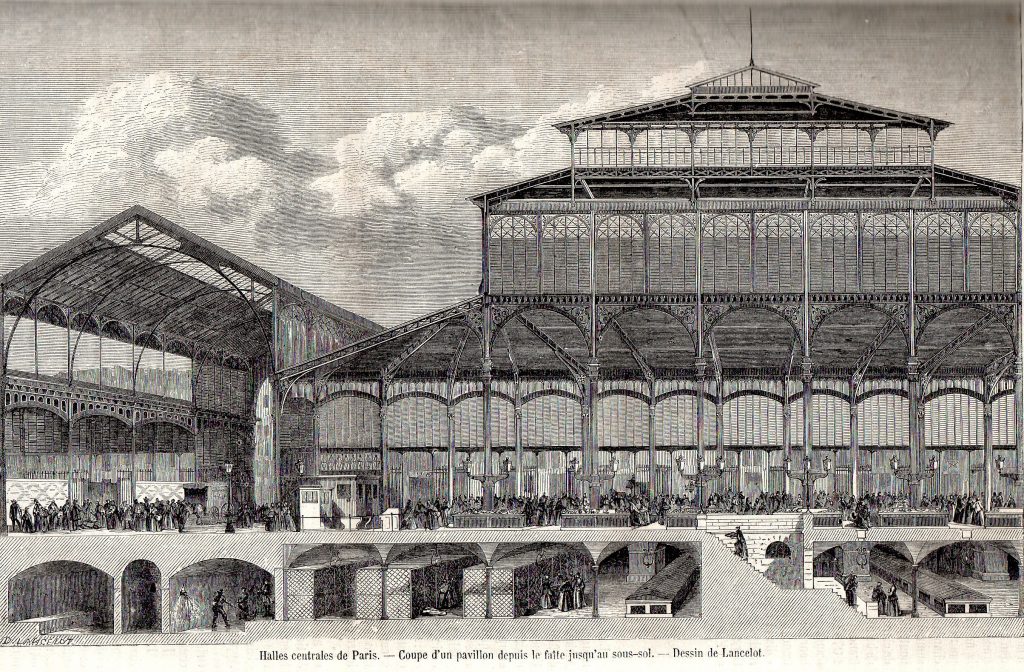

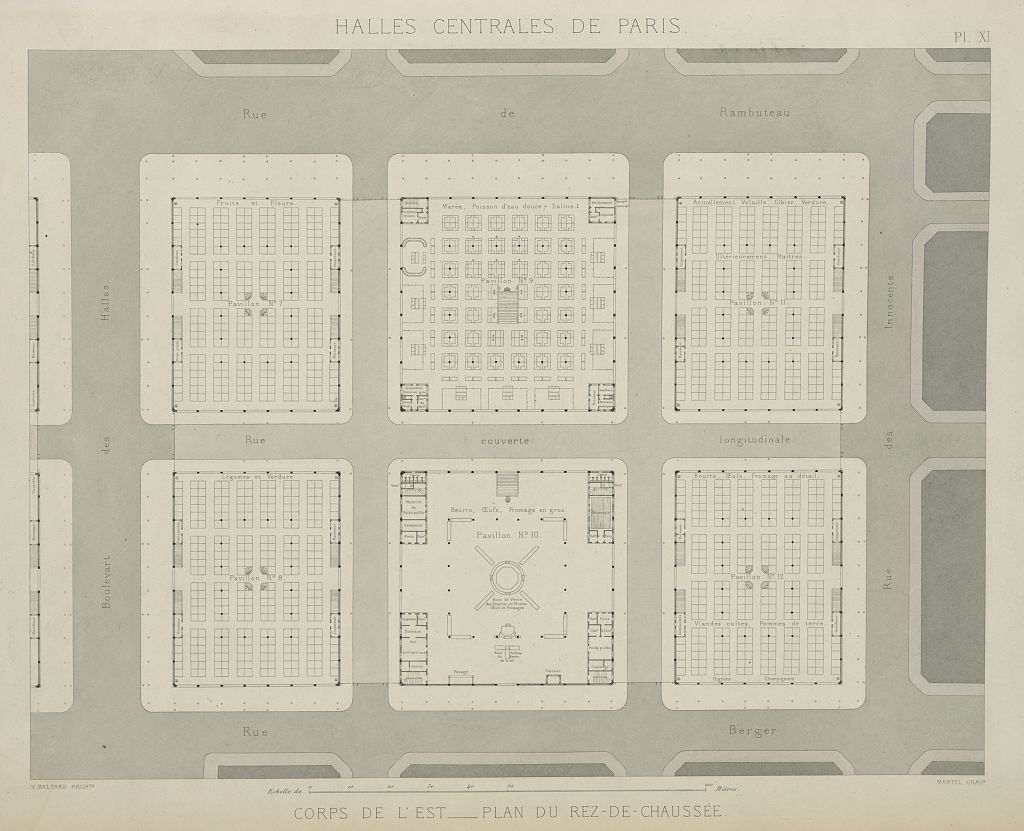

Architecturally, these ideals were manifested by architect, Victor Baltard in 1853, in the form of twelve cubic pavilions of Iron and glass arranged along an axis aligned with the existing rotunda, the Halle au Blé. The separate pavilions were connected along the central axis by a large covered alley, that branched out into four smaller ones. The material qualities of iron and glass, that of lightness and transparency, provided a seemingly lightweight enclosure that was illusive to the heavily designed systems of circulation within the building. The new Halles served to align with the new ideal of urban order through improvements in the circulation of food, water, air, and light under one roof.

On the ground floor, goods are contained to be sold within designated pavilions for each type of food. Storage space for provisions existed below ground, cutting down on ground level clutter and circulation. Among the storage, there also existed abattoirs, warehouses and water tanks for fish.8 Additionally, an elaborate drainage system efficiently maintained the flow of water and waste underneath the structure.9 In order to Maintain a hygienic atmosphere, the circulation of air was encouraged through the inclusion of high ceilings in the glass encased pavilions.

Each pavilion, though distinct in the type of food they contained and sold, appeared architecturally uniform. Such lack of architectural differentiation gave way to the standardization of units that would allow for ease of control over stall rents, opening hours and cleanliness10 as well commerce and commercial activities.11 In concurrence with changes in written regulations, this new organization would come to place restrictions and qualifications for who could buy and sell under the roof of Les Halles.12 In this sense, the standardization of stalls would lead to a standardization of behaviour and demeanour among its occupants. Profitable positions were given to more proper stall owners , while others who lacked certain qualifications were positioned at the periphery.13 There also lies a shift in behaviour between stall holders and consumers. The standardized stalls provide a sense of solidarity and alliance among stall holders, and therefor reducing consumer agency in terms of choice and bargaining power.14

“Les Halles was remade by a rational and hygienic architecture-urbanism that created ideal conditions for commercial trade and capitalist relations.”15

The attempt to clean up the spacial organization of the city, and the establishment of an “urban order” through the enclosed market hall extended further control over the behaviour of human bodies within the space. Cleaning up the public realm underhandedly involves “cleaning up” its inhabitants, a process that undoubtedly intertwined with class relations. The early modern Market hall symbolizes a transition toward newly formed bourgeois sensibilities of order and efficiency and homogenization of the marketplace.

Notes

- Rosemary Wakeman, “Fascinating Les Halles,” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 47.

- Ibid, 48.

- Ibid, 49.

- Meredith TenHoor, “Architecture and Biopolitics at Les Halles,” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 73.

- Manel Guàrdia, José Luis Oyón, and Sergi Garriga, “Markets and Market Halls,” in The Routledge Companion to the History of Retailing (London: Routledge, 2019), 103.

- Ibid, 102.

- Rosemary Wakeman, “Fascinating Les Halles,” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 50.

- Thomas A. Markus, “Exchange,” in Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types, (London: Routledge, 2013), 305.

- Ibid.

- Thomas A. Markus, “Exchange,” in Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types, (London: Routledge, 2013), 303.

- Meredith TenHoor, “Architecture and Biopolitics at Les Halles,” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 79.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thomas A. Markus, “Exchange,” in Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types, (London: Routledge, 2013), 303.

- Rosemary Wakeman, “Fascinating Les Halles,” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 58.

Bibliography

Guàrdia, Manel, José Luis Oyón, and Sergi Garriga. “Markets and Market Halls.” In The Routledge Companion to the History of Retailing. 1st ed., 101-118. London: Routledge, 2019.

Markus, Thomas A. “Exchange.” In Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types, 300-316. London: Routledge, 2013.

TenHoor, Meredith. “Architecture and Biopolitics at Les Halles.” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 73-92.

Wakeman, Rosemary. “Fascinating Les Halles.” French Politics, Culture and Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 46-72.