“Jerusalem is a port city on the shore of eternity.” – Yehuda Amichai.

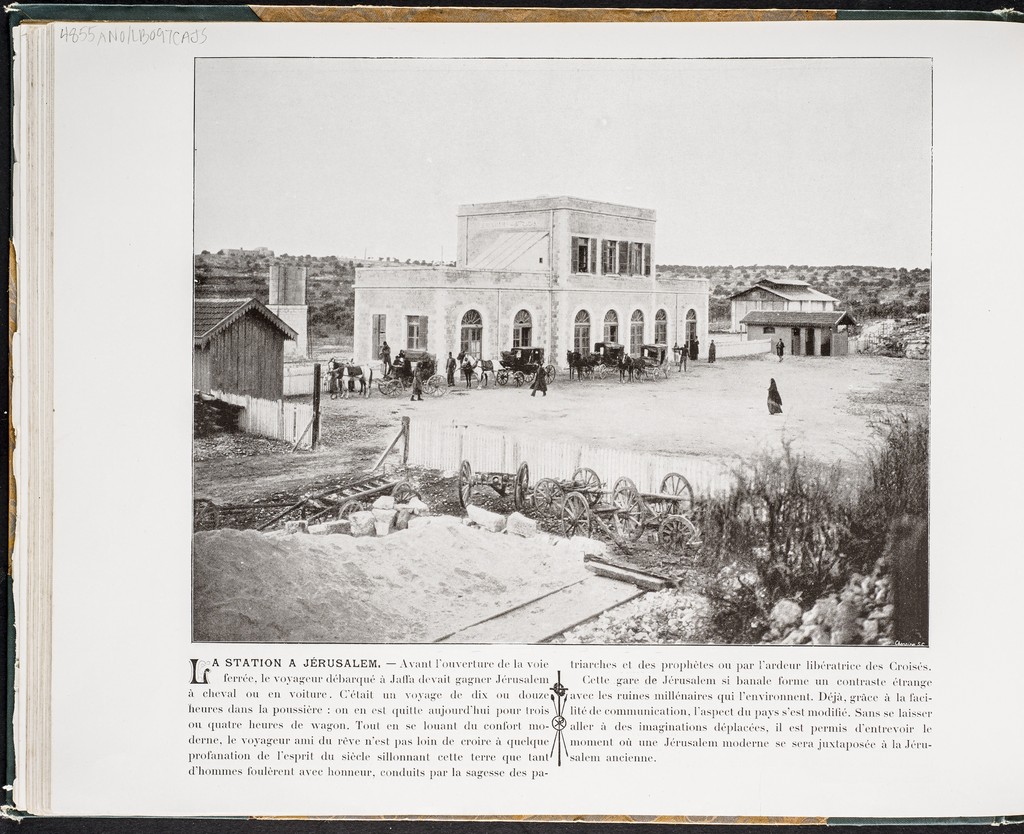

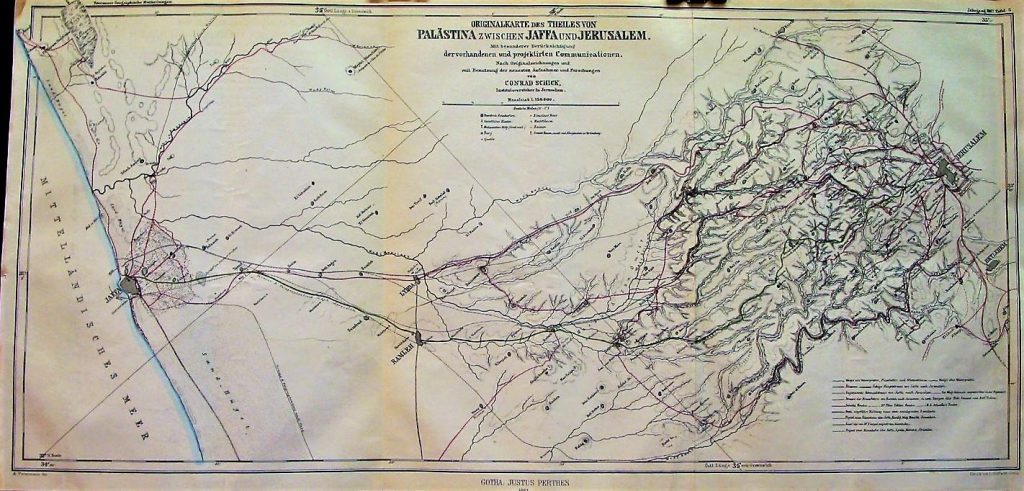

The buildings we see, especially public ones, send back a signal of their deeper purpose. Some of these buildings are famous (architecturally speaking) and some simply remind us of the events and ambitions of the places and people that built them1. The Jerusalem Rail Station is typical of the latter. At the west end of the Ottoman empire, in the twilight of their dominion, a rail station was built outside the walls of ancient Jerusalem. The station was designed in the baroque style and built by Turkish officials approximately one mile outside the walls of the city. It is unremarkable architecturally but very significant because of its site and history. The station was built in close proximity to the German Colony, one of the first successful immigrant neighborhoods built outside the walls of Jerusalem. This choice for its site perhaps foreshadowed how the station would usher in a new era of growth for Jerusalem.

The Jerusalem railway station is an artifact of a unique form of religious colonization, one where the location and history of an area are the resources to be extracted. The exploitation of this resource involved bringing people in instead of shipping resources out. The consequences of this in the short term may have been new opportunities for tourism and growth but in the long term, the railway to Jerusalem helped to fuel the complicated idea of who the city belongs to. Furthermore, the creation of the railway from Jaffa to Jerusalem and its stations document the Ottoman empire’s attempts to modernize and streamline commerce while retaining control of its lands and people. The station in Jerusalem was a statement of imperial intention. It was thought that the Ottoman empire was hesitant to develop railways because conquering forces could then use the rails to get to places where geography was part of the defense2. Even given this risk, the line between Jaffa and Jerusalem would become a reality.

In the 19th century, railways were being built all across the middle east, port cities and resource-rich areas became strategic nodes for the distribution of goods and also the influx of people. The Ottoman empire was ambitious in the construction of rail lines in this era, between 1850 and 1914 almost 7500 kilometers of the track was laid throughout the ottoman empire3. Most of the cities that warranted a rail station had extractive potential or could service a port. The investment capital needed to justify the laying of tracks and their subsequent maintenance meant that each stop on a rail line was carefully planned. Jerusalem is unique in this sense. It is unlike other cities in the fact that it has little to offer in terms of natural resources. Its value is associated with its religious sites and structures and its long history. The city of Jerusalem is far inland and on top of a plateau surrounded by jagged cliffs. The geographic challenges were subordinate to the potential seen by planners and investors. The railway was largely financed by foreign investors that had seen the value of a rail station in Jerusalem and also saw an opportunity to associate themselves with the area4.

At the time that the railway was built Jerusalem’s population was small at around 10 000 people. This small population however was quite diverse. Due to the religious significance of the area, many groups lay claim to it. Jews, Muslims, Christians, and of course the indigenous Palestinian population made up the bulk of the inhabitants. The diversity of the inhabitants was and still is, a cause of tension in Jerusalem. As the access to the area improved other groups (often called pilgrims) made their way to Jerusalem further complicating how the land was occupied and distributed. Jerusalem had been attracting foreigners for many years. But an influx of pilgrim settlers (mostly Russian and German) in the mid-1800s caused Jerusalem to swell beyond its walls5. The German settlers had bought land outside the walls built by the Ottomans in the 1500s and made a colony for themselves. They imported the vernacular architecture of their homeland and mixed it with local types and materials. It was near the German colony that the Jerusalem Train Station would be built. This decision signaled the start of a new era for the city. By the end of world war two, most of the descendants of the German colonists would be exiled from the area but the impact they made on legitimizing the colonization of outer Jerusalem would endure.

In the 1870s growing numbers of Jewish settlers also came to Jerusalem6. With the increase in population, the need for better means of transportation from the port city of Joffa arose and the plans for a rail connection began to accelerate. To finance the railway to Jerusalem the Ottoman government reached out to their subjects to help finance the project7. Foreign companies were also eager to be a part of the project. A French railway company spearheaded the project and in 1889 the railway was officially open. The new rail was instantly popular. Although it was made as a narrow-gauge single-track line, the train was able to get large numbers of people to and from Jerusalem. It must be remembered that all of these events were occurring at the end of the Ottoman empire. This is significant because such a large investment in access to Jerusalem posed a risk. The significance of Jerusalem as a religious destination meant that the access provided by the railway could further dilute Ottoman influence in the city. At the opening ceremony of the Jerusalem station not only were Ottoman officials present but also representatives from England who would later occupy and govern Palestine. Furthermore, Jewish Rabbis and Muslim leaders prayed and offered sacrifices at the station. This level of participation and pageantry would not be present at other stations and demonstrates how important Jerusalem was to so many.

Rail travel illustrates the annihilation of space by time. Historically the trip from Jaffa to Jerusalem could take between 17 hours to 3 days and could be expensive. The trip was dangerous and travelers would need to seek overnight lodging. The train shortened this trip to 3 hours and cost 1$8. The result was a huge influx of people who now perceived the city as more of an attainable destination. One reporter at the time lamented this new ease of access, stating that the difficulty of access was what made Jerusalem special. He warned that the train would secularize the city9. However, the opposite phenomena occurred. As Jerusalem grew it became more meaningful and more contested. The city was often the setting of battles between the same ethnic and religious groups that once shared its walls.

The Jerusalem station was last used for its original purpose in 1998. Now it is a retail space. The station was once a mile outside the city’s limits and now expansion has enveloped it and stretched far beyond.

The station reminds us how it was a major part of ushering in this growth. And also how unique it is to see a city like Jerusalem expand during the colonial era when it had no significant resources to extract. The Ottoman planners knew that Jerusalem was at the end of the road so to speak and that the primary function of a rail line would be to serve tourism. As such the natural progression of events meant that more and more people had to be brought to Jerusalem to justify the maintenance and operational costs of the rail line and its stations. But often the people who visited stayed, and the city grew even more.

The railway was a critical element in facilitating the colonization of Jerusalem. Beyond being a transport hub, the station in Jerusalem is a reminder of how many empires used the technology of railways to expand their reach and extractive power. Jerusalem had little to offer in this sense, but its cultural significance justified making ways to get more people to and from the city. No doubt that the railway accelerated the growth and expansion of the city, it also facilitated the continued diversification of the population for better and for worse.

Citations.

1. Railway Station as an Element of the Colonial City of Industry: Case Study Cianjur Railway Station. K Muthmainnah et al 2020 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 452

2. C, H. B. “RAILWAY TO JERUSALEM.” The Monthly Religious Magazine (1861-1869) 38, no. 6 (12,1867): 467. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/railway-jerusalem/docview/135934464/se-2?accountid=14656.

3. Nacar, Can. “Negotiating Railroad Safety in the Late Ottoman Empire: The State, Railroad Companies, Trainmen, and Trespassers.” New Perspectives on Turkey 60 (2019): 61–84. doi:10.1017/npt.2019.5.

4. Dimitriadis, Sotirios. “The Tramway Concession of Jerusalem, 1908–1914: Elite Citizenship, Urban Infrastructure, and the Abortive Modernization of a Late Ottoman City.” In Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, edited by Dalachanis Angelos and Lemire Vincent, 475-89. LEIDEN; BOSTON: Brill, 2018. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs2zk.35.

5. Daniel, Robert, and Marc Render. n.d. “From Mule Tracks to Light Rail Transit Tracks Integrating Modern Infrastructure into an Ancient City—Jerusalem, Israel,” Report.

6. Dimitriadis, Sotirios. “The Tramway Concession of Jerusalem, 1908–1914: Elite Citizenship, Urban Infrastructure, and the Abortive Modernization of a Late Ottoman City.” In Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, edited by Dalachanis Angelos and Lemire Vincent, 475-89. LEIDEN; BOSTON: Brill, 2018. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs2zk.35

7. SAFRAN, YAIR, and TAMIR GOREN. “Ideas and Plans to Construct a Railroad in Northern Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period.” Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 5 (2010): 753-70. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20775073.

8. “BY RAIL TO JERUSALEM: HARPER’S MAGAZINE.” Current Literature (1888-1912), 05, 1893, 65, https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/rail-jerusalem/docview/124812996/se-2?accountid=14656.

9. C, H. B. “RAILWAY TO JERUSALEM.” The Monthly Religious Magazine (1861-1869) 38, no. 6 (12, 1867): 467. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/railway-jerusalem/docview/135934464/se-2?accountid=14656.

Bibliography.

“BY RAIL TO JERUSALEM: HARPER’S MAGAZINE.” Current Literature (1888-1912), 05, 1893, 65, https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/rail-jerusalem/docview/124812996/se-2?accountid=14656.

C, H. B. “RAILWAY TO JERUSALEM.” The Monthly Religious Magazine (1861-1869) 38, no. 6 (12,1867): 467. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/railway-jerusalem/docview/135934464/se-2?accountid=14656.

C, H. B. “RAILWAY TO JERUSALEM.” The Monthly Religious Magazine (1861-1869) 38, no. 6 (12, 1867): 467. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/railway-jerusalem/docview/135934464/se-2?accountid=14656.

Daniel, Robert, and Marc Render. n.d. “From Mule Tracks to Light Rail Transit Tracks Integrating Modern Infrastructure into an Ancient City—Jerusalem, Israel,” Report.

Dimitriadis, Sotirios. “The Tramway Concession of Jerusalem, 1908–1914: Elite Citizenship, Urban Infrastructure, and the Abortive Modernization of a Late Ottoman City.” In Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, edited by Dalachanis Angelos and Lemire Vincent, 475-89. LEIDEN; BOSTON: Brill, 2018. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs2zk.35

Dimitriadis, Sotirios. “The Tramway Concession of Jerusalem, 1908–1914: Elite Citizenship, Urban Infrastructure, and the Abortive Modernization of a Late Ottoman City.” In Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, edited by Dalachanis Angelos and Lemire Vincent, 475-89. LEIDEN; BOSTON: Brill, 2018. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs2zk.35.

Nacar, Can. “Negotiating Railroad Safety in the Late Ottoman Empire: The State, Railroad Companies, Trainmen, and Trespassers.” New Perspectives on Turkey 60 (2019): 61–84. doi:10.1017/npt.2019.5.

Railway Station as an Element of the Colonial City of Industry: Case Study Cianjur Railway Station. K Muthmainnah et al 2020 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 452

SAFRAN, YAIR, and TAMIR GOREN. “Ideas and Plans to Construct a Railroad in Northern Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period.” Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 5 (2010): 753-70. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20775073.