Introduction

The South Kensington Museum—now the Victoria and Albert Museum—has a unique and complex history. Perhaps most well-known for its primary focus on industrial education throughout the nineteenth century, the South Kensington Museum stood distinct from other prominent art museums in London at the time. Founded in 1852, the museum followed the success of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park. Henry Cole and Prince Albert, the exhibition’s respective organizer and champion, sought to advance the goals of the exhibition and install a more permanent institution dedicated to improving the standards of British industry in the London landscape[1]. Central to their vision was the improvement in quality of product design among British manufacturers and the promotion of good taste among consumers through industrial education[2].

Using the profits generated from the Great Exhibition, Prince Albert purchased an 86-acre plot of land on which the museum currently sits in South Kensington and much of the museum’s early collection[3]. Prince Albert envisioned a network of universities, learned societies, and national museums on this large estate, in addition to the South Kensington Museum[4]. As Bruce Robertson argues in ‘The South Kensington Museum in context: an alternate history’, the focus on education was so all-encompassing that the South Kensington Museum could hardly be classified as a museum, like the National Gallery and British Museum before it. The institution’s main priority, at least until the end of the nineteenth century, was not to collect rare works of art but to educate the public on aesthetic sensibilities[5].

This characterization of the South Kensington Museum as an epicenter for education is complicated however when read within its colonial history. With the understanding that most of the objects used as teaching tools in the museum’s collection were removed from their original contexts and appropriated to prop up British industry, suddenly the museum’s educational function appears less commendable and more exploitative and dangerous in its power to communicate and reify hegemonic narratives of Imperial Britain. By studying the organizational, architectural, and administrative decisions made at the scale of the displayed object, the building, and the broader institution respectively, the specific messages they communicate about power throughout the museum’s history can understood.

The Object: a means to an end

With the resumption of trade in the 1820s following decades of war in Europe, British products were failing in both the domestic and international markets[6]. British consumers were consistently favoring French fashion over domestic products, pressuring the British government to improve the quality of its industrial production[7]. In response, a Select Committee on Arts and Manufacture established the School of Design in 1836 to train artisans and students in the principles of aesthetics[8]. Following the 1851 Exhibition, the school was absorbed by the Department of Science and Art headed by Henry Cole and charged with promoting education in art, science, and design throughout the country[9]. Cole believed that a public institution that could educate British citizenry in design was of equal importance to an artist’s education, as they possessed the purchasing power to demand high quality products[10]. Over several iterations and moves, Cole erected the South Kensington Museum in its current location in 1857 and formed the core of its collection from products purchased from the Great Exhibition and objects used by the School of Design for instruction[11].

Under Cole’s administration, the museum was strictly utilitarian. The collections of displayed objects and products were always in service of education, as evidenced by the taxonomies and labels used to curate the museum’s collection. From 1852 and until 1945, objects were arranged by material and type—textiles, ceramics, metalworks, glass, and woodworks[12]. Rather than traditionally categorizing objects by date, theme, or location, collections were spatially organized by medium to aid students and visiting artisans in studying each group’s manufacturing techniques[13]. In addition, objects in the early collection were accompanied by a label with the minimal amount of contextual information, but a lengthy explanatory analysis of the object’s formal and aesthetic qualities[14]. From the 1852 Catalogue of the Articles in the Museum of Manufactures Chiefly Purchased from the Great Exhibition, the following is an example of an explanatory analysis provided for an Indian textile:

“Remarkable for the elegance of effect produced by very simple means: by the repetition of the same small flower in the border, well balanced in form and colour. The bands of black and red, in zigzag, above and below the general border, are judicious in retaining the eye within the border, and preventing it following the diagonal lines formed by the arrangement of the small flower in the filling in[15].”

As Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn note in their Introduction to ‘Colonialism and the Object’, “when such objects are removed from their original contexts, and are subjected to appropriation and exhibition, their meanings undergo radical changes[16]“. In the same way, the exhibition of colonial objects for the British public to learn and eventually profit from erases the cultural and historical meaning the objects carry, treating each object as a resource used solely to fuel the British Empire. The organizational logic and labelling convention used by the South Kensington Museum further strips the object of its own history and reduces it to an ornamental trinket that exists only in service of its colonizer. As a center of education, the racial taxonomies the museum constructs through its curation strategies encourages the viewer to disregard the people and cultures behind each artifact and to only see the object for the economic value they hold. The museum’s deliberate organization thus demonstrates the level of control the empire exercises over its colonies and communicates the power inherent to that relationship.

The Building: establishing the ‘Other’ and the Imperial Center

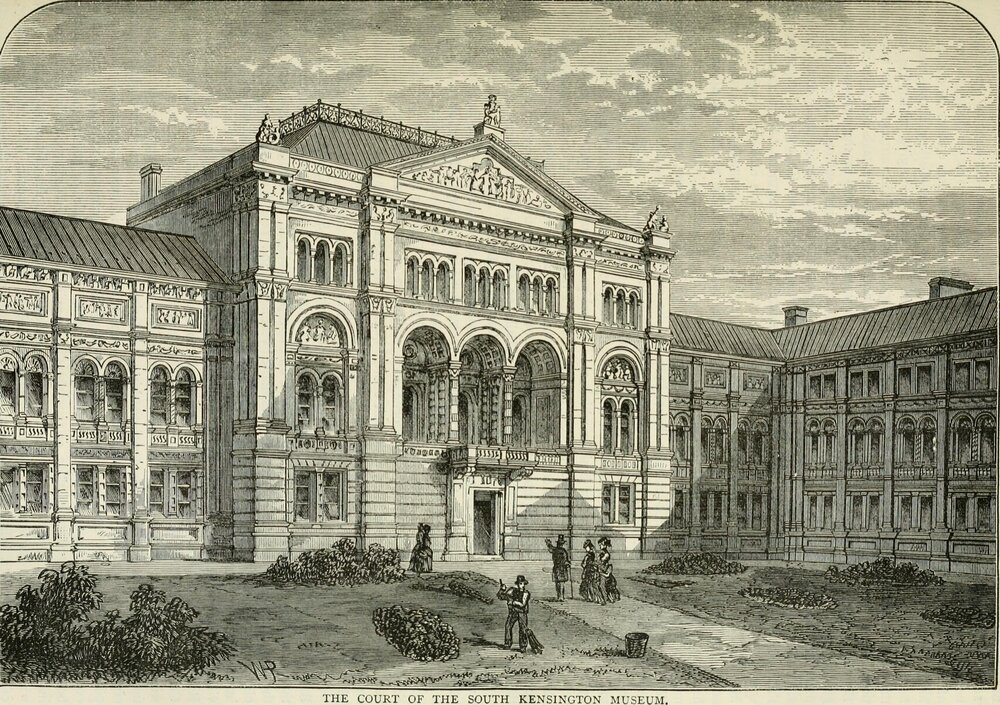

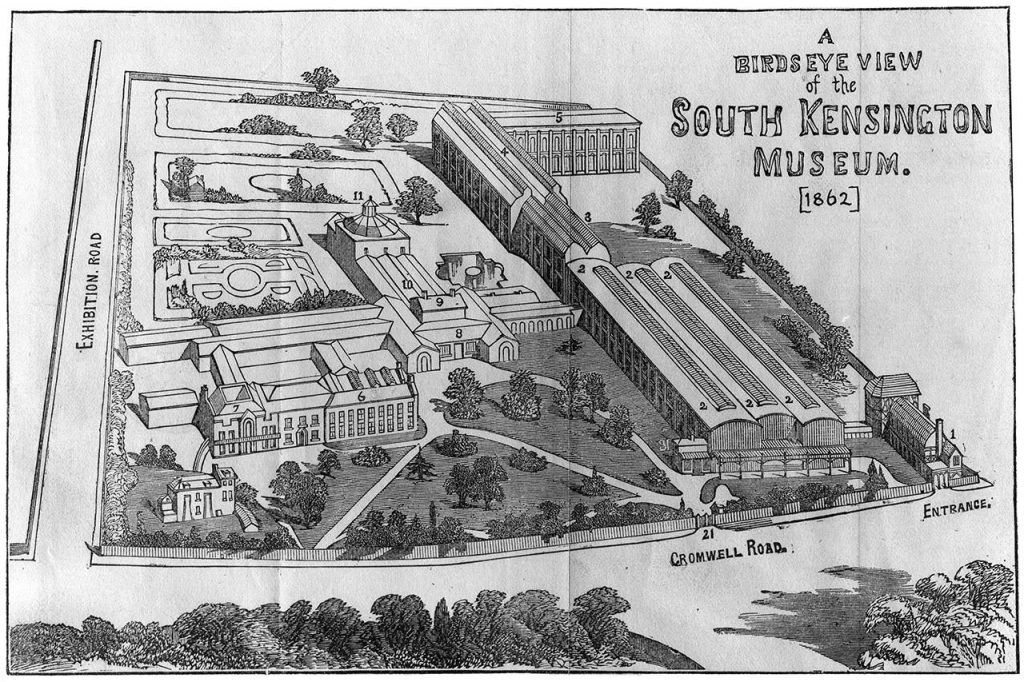

Just as the 1851 Exhibition actively promoted the commercial importance of Britain’s Imperial project in its colonies, public awareness of Britain’s colonial possessions mirrored the museum’s growing collection and display of gifts from the colonies throughout the late nineteenth century[17]. In 1862, additions were made to the main museum building to house the expanding collection. The North and South Courts were constructed using a system of glass and cast-iron, like that of the Crystal Palace[18]. Divided by a central arcade, one half of the South Court housed the Oriental Court—the museum’s collection of Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and Persian objects[19]. Around the early 1870s, a large number of casts of ancient Indian monuments and sculptures arrived at South Kensington, spurring the construction of the large Architectural Courts that like the monuments it housed was meant to impress on the visitor with an overwhelming and impressive sense of scale[20].

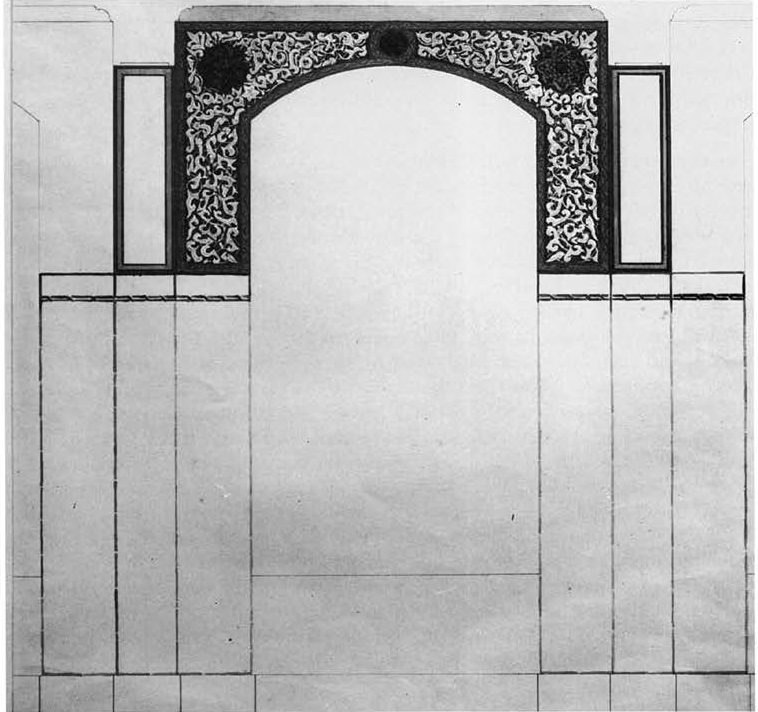

The interiors of each court were meticulously decorated, with different sections of the building drawing specific inspiration from examples from within the museum’s collection[21]. During Cole’s tenure with the museum, artists and students from the surrounding schools were responsible for decorating each new building constructed on site such that the building fabric could constantly illustrate the principals of good design to the visiting public[22]. Artists were encouraged to treat the building like a living laboratory of their workmanship and to use the principles of ornamentation they had studied from the museum’s collections[23]. The wall and ceiling decorations for the Oriental Court were for example designed by architect Owen Jones, who had previously decorated the Crystal Palace utilizing historic styles of ornament from Greek, Egyptian, and Indian examples. Similarly, the windows in the Oriental Court were designed by architect J. W. Wild in a Moorish style, a style not seen elsewhere in the museum[24].

The intricate decoration of South Kensington’s interior served two functions. The haphazard application of different cultural styles and blatant appropriation of ‘oriental’ designs in the Oriental Court functioned to emphasize and isolate the exotic ‘other’ from the West, while collapsing meaningful differences between cultures under a single ‘oriental’ umbrella term[25]. However, the detailed articulation and ornamentation of the building’s decorative schemes also functioned to highlight the newfound design and technical prowess of the institution, fortifying the museum’s legitimacy as a center of design education to students and visitors. The predominant use of glass and steel in the North and South Courts and the vastness of the Architectural Courts that elicit the Victorian sublime similarly evoke a sense of technical and cultural superiority over the collections they physically tower over. In this way, Britain as the Imperial center is positioned at the pinnacle of industrial development, while other cultures are understood to exist on the periphery of this progress.

The Institution: forming an Imperial Archive

As the collections at South Kensington grew to include objects and artifacts from South East Asia, China, Japan, Korea, and Europe, the museum constantly outgrew its galleries and necessitated the haphazard construction of new buildings every few years. In addition to the Architectural, North, and South Courts, a lecture theatre, Art Library and a East and West Court were also added to the museum complex with construction finishing in 1884 [26]. The amalgamated and at times disjointed makeup of the museum was however not lost on its visitors [27]. An architectural competition was held in 1891 to construct new galleries and a unified red brick facade that could create a coherent frontage on Exhibition and Cromwell Road, while eliminating any gaps in the museum’s elevation[28]. The competition was won by architect Aston Webb and construction of his plans began in 1899[29]. Construction ushered in the museum’s new name as the Victoria and Albert Museum and the current iteration of the building as it appears today[30].

Despite the slightly disorganized nature of the museum’s buildings, the constant additions to the complex symbolized the continued amassing of colonial assets, the centralization of information and knowledge, and the power the British Empire had around the world. As Barringer notes, the vast array of Indian colonial artifacts amassed at South Kensington granted the collection near encyclopedic status[31]. Additionally, the museum’s collection of objects and artifacts from countries it had no colonial control, such as China, Japan, and Korea were significant as it represented a symbolic ‘acquisition’ of that culture into the museum’s imperial archive[32]. By the time construction of Webb’s plans began in 1899, the South Kensington Museum had already become an essential fixture in the London cityscape. The procession of colonial objects from the Empires’ periphery to the city center along with the knowledge and power they carried symbolically positions London at the heart of the British Empire.

Conclusion

The South Kensington Museum can be most popularly characterized by it institutional focus on education and the overall improvement in the design techniques and taste of Britain’s manufacturers and citizenry. However, this reading of the museum primarily as an educational institution is not complete. Without considering the colonial history it participated, benefited from, and contributed to, the full story of the South Kensington Museum cannot be fully understood. From the specific strategies used to display museum objects, the oriental decorations made to establish the ‘other’, and the construction of a vast imperial archive, the story of the South Kensington Museum is one of imperial power and control inherent to the act of colonization.

Bibliography

Ashton, Leigh. “100 Years of the Victoria & Albert Museum.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 101, no. 4889 (1952): 79–90.

Barringer, Tim. “Re-Presenting the Imperial Archive: South Kensington and Its Museums.” Journal of Victorian Culture 3, no. 2 (March 1, 1998): 357–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13555509809505971.

Barringer, Tim. “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project.” In Colonialism and the Object, 1st ed., 11–27. Routledge, 1998. https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/chapters/mono/10.4324/9780203350683-9/south-kensington-museum-colonial-project-tim-barringer-tom-flynn.

Barringer, Tim, and Tom Flynn. “Introduction.” In Colonialism and the Object, 1st ed., 1–8. Routledge, 1998. https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/chapters/mono/10.4324/9780203350683-9/south-kensington-museum-colonial-project-tim-barringer-tom-flynn.

Burton, Anthony. “The Uses of the South Kensington Art Collections.” Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 1 (May 1, 2002): 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/14.1.79.

Cao, Lilly. “The Educational Objectives of the South Kensington Museum.” Erudition Magazine, September 2, 2020. https://www.eruditionmag.com/home/the-educational-objectives-of-the-south-kensington-museum-developing-british-industry-through-the-cultivation-of-aesthetic-taste.

Dutta, Arindam. “The South Kensington Juggernaut.” Edited by Elizabeth Bonython and Anthony Burton. Oxford Art Journal 27, no. 2 (2004): 241–45.

Gillespie, Hope Elizabeth. “Imperialism, Identity, and Image: Looking at Colonial Objects in English Museums.” Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, September 11, 2020. https://cmsmc.org/publications/imperialism-identity-and-image.

Robertson, Bruce. “The South Kensington Museum in Context: An Alternative History.” Museum and Society 2, no. 1 (2004): 1–14.

Spear, Jeffrey L. “A South Kensington Gateway from Gwalior to Nowhere.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 48, no. 4 (2008): 911–21.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “V&A · Building the Museum.” Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/building-the-museum.

Waterfield, Giles. “Museums: Treasuries or Playgrounds?” Journal of Victorian Culture 3, no. 2 (March 1, 1998): 353–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13555509809505970.

Notes

[1] Robertson, “The South Kensington Museum in context”, 1

[2] Barringer, “Re-presenting the Imperial Archive”, 358

[3] V&A, “Building the Museum”

[4] Robertson, “The South Kensington Museum in context”, 2

[5] Robertson, “The South Kensington Museum in context”, 3

[6] Burton, “South Kensington art collections”, 81

[7] Dutta, “The South Kensington Juggernaut”, 242

[8] Robertson, “The South Kensington Museum in context”, 4

[9] Ibid.

[10] Burton, “South Kensington art collections”, 82

[11] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 13

[12] Ashton, “100 Years of the Victoria & Albert Museum”, 81

[13] Burton, “South Kensington art collections”, 87

[14] Burton, “South Kensington art collections”, 83

[15] Ibid.

[16] Barringer & Flynn, Introduction, 2

[17] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 12

[18] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 15

[19] Barringer, “Re-presenting the Imperial Archive”, 367

[20] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 17

[21] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 15

[22] Barringer, “Re-presenting the Imperial Archive”, 363

[23] Barringer, “Re-presenting the Imperial Archive”, 366

[24] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 16

[25] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 17

[26] Ashton, “100 Years of the Victoria & Albert Museum”, 85

[27] Robertson, “The South Kensington Museum in context”, 6

[28] V&A, “Building the Museum”

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 23

[32] Barringer, The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project, 19