A Selective Curation and Distribution of Knowledge

The Natural History Museum in London established in 1881 was designed by the Architect Alfred Waterhouse under the close guidance of Richard Owen, the Superintendent of the museum at the time. It exhibits a vast range of specimens and is recognized as the pre-eminent center of natural history and research in the world. As the center of overlapping conflicts about natural science and architecture, arguments were raised both within the scientific community and between the proposed architects1. Additionally, the disputes about knowledge and institutional claims were inherently related to the colonial past of the British Empire, which are commonly missing from the interpretation of natural history collections2. The erection of the Natural History Museum ultimately provided a response to the ongoing conflicts through a purposefully designed spatial arrangement, while selectively distributing knowledge and acknowledging aspects that would glorify the colonial empire.

Defining Nature

The architectural development of the Natural History Museum in London was significantly affected by the conflicting definition of nature in the Victorian era, which the definition ranged from nature as the unwritten Book of God to nature as secular science3. Determining a way to present natural science to the general public was the subsequent discussion between naturalists, politicians, and scientists. In the early 1850s, the breadth of the Museum’s display was debated between Richard Owen, an upper-class conservative natural theologian, and Thomas Huxley, a middle-class secular evolutionist. Owen preferred a massive display of the entire imperial collection, whereas Huxley favored a smaller museum as a research center that was dedicated to scientists only.

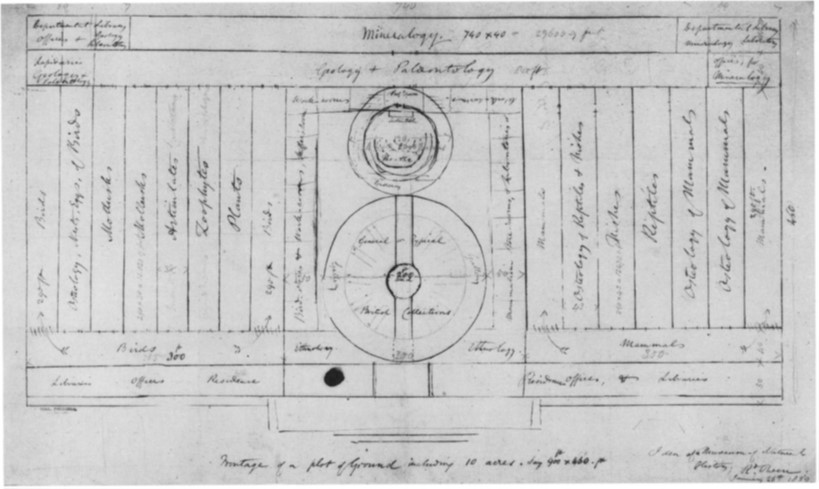

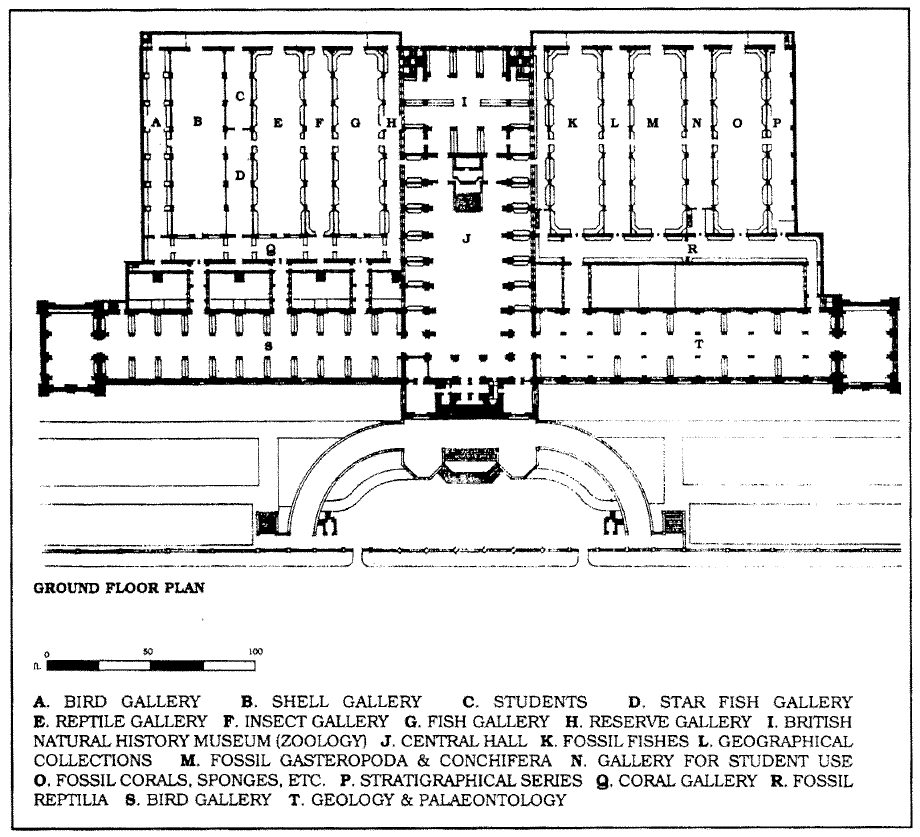

According to the earliest surviving plan of the Museum sketched by Owen in 1859, visitors would first encounter a round room full of British natural objects as they enter the Museum. The centrality of the British collection revealed Owen’s nationalism which was conveyed through the architectural expression4. The plan was most famous for its “comb-like” space, which was first proposed in 1982 by Peponis and Hedin: “On the ground floor the building was basically organized as a comb-like plan with a hall at the center of its major axis”5. The front galleries that form the façade of the building are like the spine of a comb, whereas the rear galleries that are extended vertically from the spine are the teeth of a comb. By applying the idea of comb-like space to examine the plans of the Natural History Museum developed in different periods, it is surprising to find a high consistency in Owen’s first plan sketched in 1859 [Fig. 1] and the final plan by Waterhouse in 1881 [Fig. 2]. Thus, Owen’s sketch had a powerful influence on the subsequent designs.

At the time when Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was just beginning to link the living and extinct species, as the opponent of Darwinism, Owen insisted a clear segregation between them both in display and in the ornamentation of the Museum6. Therefore, the central hall that penetrates the spine resulted in the discontinuity between the convex of the teeth, which curated the visitors in two distinct directions, and would be difficult for them to reach the opposite side once entered the chosen side.

The Untold Stories of the Colonial Past

Besides curating the visitors through a carefully designed spatial distribution of the collections, the information regarding the history of the Museum was also selectively presented to neglect the colonial past. “Natural history museums as we know them wouldn’t exist without the colonial period,” says Holger Stoecker, an African studies expert at Humboldt University7. Much like many other European natural museums, the narratives behind the collected specimens in the Natural History Museum in London also fail to fully acknowledge the enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples of the Americas. Despite some being mentioned in the documents, people of color were mainly unnamed, and their scientific contributions were consistently omitted8.

In London’s Natural History Museum, the ceiling of the grand Hintze Hall, also known as the “Gilded Canopy”, is composed of 162 panels illustrating plants from across the world to showcase the empire’s global reach. One of them depicts Quassia amara, and it was named after Graman Kwasi, an enslaved healer and botanist. Kwasi was known for his discovery that Quassia amara could be used to treat infections caused by intestinal parasites. Despite his notable contribution, there was no acknowledgement of Kwasi in the new 2017 gallery interpretation of the Hintze Hall ceiling at the Natural History Museum9. Indeed, he was only one of the countless enslaved people who had contributed to the specimen collection, and exemplifies the hidden history of the indigenous and African people who received little or no recognition for their remarkable inputs.

Besides the omission of the contributions from people of color, the formation of the museum encompassing slave trade and other exploitative practices were also made less visible to the public. One of the most important colonial stories of the collections was about the specimens collected by Sir Hans Sloane, which contributes to the core collections of the museum. Sloane was an Anglo-Irish physician, naturalist, and collector during the beginning period of European colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade10. He departed on his travels at the age of 27, and eventually settled in Jamaica where he studied and collected over 800 specimens. These documents and specimens later became the founding collections of London’s Natural History Museum. However, it was seldomly mentioned that Sloane’s medical and scientific careers were directly funded by profits from slavery. As a plantation doctor in Jamaica, Sloane was complicit in slavery and the transfer of plants by slave traders from West Africa to the Caribbean11. Therefore, slave trade is inextricable linked to the specimens collected by Sloane, which many were subsequently housed in the Natural History Museum.

Conclusion

The development of the Natural History Museum in London was truly a conflicted cultural endeavor, as it was designed to present and curate the ever-changing science and nature through a relatively permanent architectural gesture. Despite its prominent impacts to the field of natural science, the Museum’s inherent colonial past is not neglectable as many of the specimens were collected from the colonial peripheries accompanied with violence, trauma, and exploitation practices. By revealing the hidden past, widely acknowledging the original source of the collections, and recognizing the contributions of people from all backgrounds, one might be able to render a more inclusive and comprehensive history of the Museum.

Footnotes

- Forgan, Sophie. “Building the Museum: Knowledge, Conflict, and the Power of Place.” Isis 96, no. 4 (December 1, 2005): 577. https://doi.org/10.1086/498594

- Das, S. & Lowe, M. “Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections.” Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 6 (2018): 4. http://www.natsca.org/article/2509

- Yanni, Carla. “Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 3 (1996): 276. https://doi.org/10.2307/991149

- Yanni, Carla. “Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 3 (1996): 279. https://doi.org/10.2307/991149

- Huang, Hsu. “Mapping of Knowledge in the Natural History Museum: Richard Owen’s Naturalistic Ideas and Spatial Layouts of the Natural History Museum in London.” Collection and Research (December 1, 2008): 58. https://doi.org/10.6693/CAR.2008.21.6.

- Lotzof, Kerry. “Alfred Waterhouse and His Cathedral to Nature.” Natural History Museum. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/alfred-waterhouse-museum-building-cathedral-to-nature.html.

- Imbler, Sabrina. “In London, Natural History Museums Confront Their Colonial Histories.” Atlas Obscura. Atlas Obscura, February 6, 2020. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/decolonizing-natural-history-museum.

- Das, S. & Lowe, M. “Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections.” Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 6 (2018): 8. http://www.natsca.org/article/2509

- Das, S. & Lowe, M. “Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections.” Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 6 (2018): 10. http://www.natsca.org/article/2509

- Davis, Josh. “Are Natural History Museums Inherently Racist?” Natural History Museum, July 16, 2019. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2019/july/are-natural-history-museums-inherently-racist.html.

- Das, S. & Lowe, M. “Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections.” Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 6 (2018): 11. http://www.natsca.org/article/2509

Bibliography

Das, S. & Lowe, M. “Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections.” Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 6 (2018): 4 ‐ 14. http://www.natsca.org/article/2509

Davis, Josh. “Are Natural History Museums Inherently Racist?” Natural History Museum, July 16, 2019. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2019/july/are-natural-history-museums-inherently-racist.html.

Forgan, Sophie. “Building the Museum: Knowledge, Conflict, and the Power of Place.” Isis 96, no. 4 (December 1, 2005): 572–85. https://doi.org/10.1086/498594

Huang, Hsu. “Mapping of Knowledge in the Natural History Museum: Richard Owen’s Naturalistic Ideas and Spatial Layouts of the Natural History Museum in London.” Collection and Research (December 1, 2008): 51–77. https://doi.org/10.6693/CAR.2008.21.6.

Imbler, Sabrina. “In London, Natural History Museums Confront Their Colonial Histories.” Atlas Obscura. Atlas Obscura, February 6, 2020. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/decolonizing-natural-history-museum.

Lotzof, Kerry. “Alfred Waterhouse and His Cathedral to Nature.” Natural History Museum. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/alfred-waterhouse-museum-building-cathedral-to-nature.html.

Yanni, Carla. “Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 3 (1996): 276–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/991149

Images

[Fig. 1] Richard Owen, Natural History Museum, plan, 1859

[Fig. 2] Alfred Waterhouse, Natural History Museum, plan, 1879-1881. Drawing after plan published in The Builder (19, May, 1883)

[Fig. 3] Quassia amara, a decorative ceiling panel from Hintze Hall