Write a blog that hyperlinks your research on the characters in GGRW according to the pages assigned to you. Be sure to make use of Jane Flick’s reference guide on you reading list.

For this blog assignment, I was assigned pages 412-416 the 1993 edition of Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water and there are three specific sections of this passage that I will divide my analysis upon.

Part 1 (412-413)

Alberta Frank and Lionel

Alberta Frank and Lionel

In section one Alberta is the main character and the two pages focus mainly on Lionel and her discussing her surprise pregnancy. Alberta is the main female character in the realist story and her name could allude to the province of Alberta or to the famous Frank Slide of 1903. In Jane Flick’s “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water” Flick discusses that the Frank Slide is “one of the disaster dates that Dr. Hovaugh tracks” (Flick 144), supporting the allusion of her name. Alberta is the lover of both Lionel and Charlie and would like to have a child, however, she does not want a husband or marriage. Her pregnancy is completely unexpected to her and is Coyote’s doing, which I will discuss later in this post.

Part 2 (414-415)

Sir Clifford Sifton and Lewis Pick

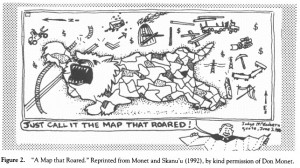

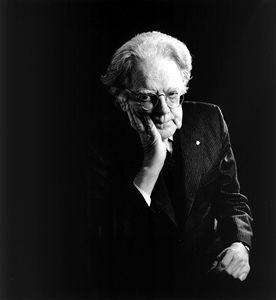

Sir Clifford Sifton is a direct reference to the historical figure, Clifford Sifton (top photo), who was an “aggressive promoter of settlement in the West through the Prairie West movement, and a champion of the settlers who displaced the Native population. Federal minister of the Interior and Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Laurier ‘s government from November 1896.” (150) In this section of the book, Siffton is accompanied by Lewis Pick who I have discerned to be a reference to Lewis A. Pick (bottom photo), the head engineer in New Orleans during the Mississippi River Flood of 1927. I think that the reference to the Mississippi flood is to correlate the flooding dam to an American disaster. When the earthquake hits the men “were knocked to the ground, and as they tried to stand, they were knocked down again. It was comical at first, the two men trying to find their footing, the cars smashing into the dam, the lake curling over the top. But beneath the power and motion there was a more ominous sound of things giving way, of things falling apart” (King 414). This is a reference to the men who are representative of Western colonialism not taking things seriously until it is to late and everything falls apart for them. The flooding is a metaphor for Western interference within Aboriginal peoples lives and the power they have to fight back.

Dr. Joseph Hovaugh, Babo Jones, and Bill Bursum

Dr. Joseph Hovaugh is a reference to Northrop Frye and his view of literature as a closed entity. This is understood when the water swept up his and Babo’s cars and all he could think about was how this disaster was written in the book he had:

“Dr. Hovaugh sagged against the bus, took out the book, and held it up. ‘It’s all here,’ he said to Babo. ‘I was right, after all.’

‘Sorry about your car,” said Babo.

‘The Dates.’

‘Looks like I lost mine, too.’

‘The places.’

Babo looked at Dr. Hovaugh, and then she turned and watched the lake race for the breach in the dam” (415).

Dr. Hovaugh is also representative of King’s love for oral storytelling as his name sounds like Jehovah when it is verbally spoken, however when reading, it does not come across this way. Hovaugh is a representation of Christianity within the book which is further supported by Babo who is mostly surrounded by. Although Babo Jones is not a major character in this scene, she “may be one of the three Wise Men of the East (the black King) following the mysterious star/light, indicated by the “westward leading” clue (276)—to Blossom and Alberta’s mysterious pregnancy” (Flick 145).

Bill Bursum reacts differently than both Babo and Dr. Hovaugh in this scene when the lake is flooding. Rather than subtly sitting by

like Babo or being completely consumed in something else like Dr. Havough, Bursum kind of freaks out. “he stood transfixed for a moment, and then he began walking down to the lake, trotting after the retreating water. ‘Now what’s gone wrong?’ he shouted, breaking into a run. . . ‘What the hell has gone wrong now?'” (415). Bursum represents a

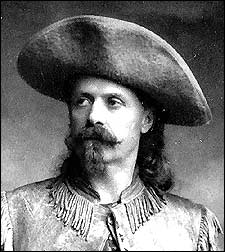

person who is not flexible to change and becomes overwhelmed at the loss of control. “King combines the names of two men famous for their hostility to Indians; Holm O. Bursum (1867-1953) (top photo). . . and the Buffalo Bill part of the name . . . William R Cody (1846-1917)“(148) (bottom photo). Bursum proposed the Bursum Bill of 1921 which intended to take away large portions of land from the Pueblo Natives and give it, and water rights, to non-Indians. Bill Bursum’s reaction to the water is representative of Holm O. Bursum’s reaction to the blocking of the Bursum Bill of 1921. As he thought it would be a sure thing and that there would be nothing preventing the passing of the bill, when everything started to go wrong he was overwhelmed.

Part 3 (416)

Coyote and The Four Indians – Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye

The four Indians represent predominant European and Western ideas of white power and colonization and I will briefly summarize Flick’s description of each of the four and of Coyote. The Lone Ranger is a “hero of western [stories] . . . At the centre of stories about the Texas Rangers and the lone survivor of a raid. He is a Do Gooder. The Texas Rangers myth has it that one ranger could be sent to clean up a town” (141). Hawkeye is “Another adopted “Indian” name. Most famous of the frontier heroes in American literature, when the frontier was in the East— Appalachia, before the frontier “moved” West” (141). Robinson Crusoe is a character based on the true story of Alexander Selkirk who was deserted on an island but managed to survive. “Crusoe survives through ingenuity and finds spiritual strength through adversity. . . King mocks Crusoe’s passion for making lists and for weighing the pros and cons of various situations” (142). Ishmael is a character from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick who survives when Moby Dick destroys Pequod “by staying afloat on Queequeg’s coffin. The name is Biblical: Gen.15.-15” (142). Finally, Coyote “The familiar trickster figure from First Nations/Native American tales, an especially important personage in the mythology of traditional oral literature of Native North America; one of the First People, “a race of mythic prototypes who lived before humans existed. They had tremendous powers; they created the world as we know it; they instituted human life and culture—but they were also capable of being brave or cowardly, conservative or innovative, wise or stupid” (143).

The last part of my section is a conversation between Coyote and the four Indians that basically summarizes the last few pages regarding the flood and Alberta’s pregnancy. This section refers to Coyote being God and that he/she is the reason for Noah’s flood, the conception of Jesus in Mary, Alberta’s pregnancy, and Christianity. Page 416 begisn with Coyote immediately denying that he had any part in the earthquake “I didn’t do it!” (King 416) to which Robinson Crusoe replied “The last time you fooled around like this the world got very wet” (416) and Hawkeye added “and we had to start all over again” (416). This is alluding to Coyote, not God, being responsible for Noah’s Flood (Flick 164). Coyote exclaims that he may have made a mistake with the earthquake but he was also useful;

“‘But I was helpful too. That woman who wanted a baby. Now that was helpful.’

‘Helpful!’ said Robinson Crusoe. ‘You remember the last time you did that?’

‘I’m quite sure I was in Kamloops,’ says Coyote.

‘We haven’t straightened out that mess yet,’ said Hawkeye” (416).

This conversation between Coyote, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye is alluding to the conception of Jesus Christ being the work of Coyote “rather than Mary’s own sinless conception” (Flick 164). The emphasis of the italisized “that” could also be a reference to the formation of the entire Christian religion, “the result of Mary’s pregnancy, one of Coyote’s mistakes” (164).

The section of Green GRass Running Water that I was assigned is extremely important to the book as it is riddled with religious allusions and forces the reader to breach the cultural barrier to fully understand.

Important Symbols, all directly from Jane Flick’s Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water

“PINTO (23) Ford automobile. Plains horse. A piebald or “painted” pony associated with Indians of the Plains. Note that Pinto ponies are promi nent in the drawings of the Cheyenne imprisoned at Fort Marion, described in Alberta’s lecture (19). Jokes about naming cars after horses, Indians and explorers may be at work here, as well as the play on words with Columbus’s ship, the Pinta. Babo thinks “the Pinto [in the puddle] looked a little like a ship,” and then, “not exactly a ship . . . Not a ship at all” (27). At the dam episode, Babo recognizes the red Pinto as “The cars [sail] past the bus” (406).

NISSAN, THE PINTO AND THE KARMANN GHIA (407) The Pinto is the first of a series of jokes about the disappearing cars that go over the dam. The three ships of Columbus on the voyage sponsored by Isabella of Spain were the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. The belief that their ships would fall off the edge of the world is often (falsely) attributed to old-world mariners. Note another minor funny bit: Dr. Hovaugh drives the slightly more upscale car; the Karmann-Ghia is white and a convertible, just the thing for a theological figure on tour” (Flick 146)

“THE CARS TUMBLED OVER THE EDGE OF THE WORLD (414) Recalls the belief falsely attributed to Old World mariners that the world was flat, and that they would sail over the edge” (164).

Works Cited

“BBC – History – Scottish History”. Bbc.co.uk. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

“Bible Gateway Passage: Genesis 5:32-10:1 – New International Version”. Bible Gateway. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature161/162 (1999). Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

“Jehovah’S Witnesses—Official Website: Jw.Org”. Jw.org. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

“Mississippi River Flood Of 1927 | American History”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web.30 Mar. 2016.

“New Mexico Office Of The State Historian | Places”. Newmexicohistory.org. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

“PRX”. Beta.prx.org. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

“Texas Rangers – Making Order Out Of Chaos”. Legendsofamerica.com. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

“The Ledo Road – Lieutenant General Lewis A. Pick”. Cbi-theater.com. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

Alberta, Government. “Frank Slide Interpretive Centre Frank Slide Story”. History.alberta.ca. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

Ayre, John. “Northrop Frye”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. N.p., 2001. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

Hall, David. “Sir Clifford Sifton”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. N.p., 2001. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. “Moby-Dick; Or, The Whale”. Americanliterature.com. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

PBS,. “PBS – THE WEST – William F. Cody”. Pbs.org. N.p., 2001. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.