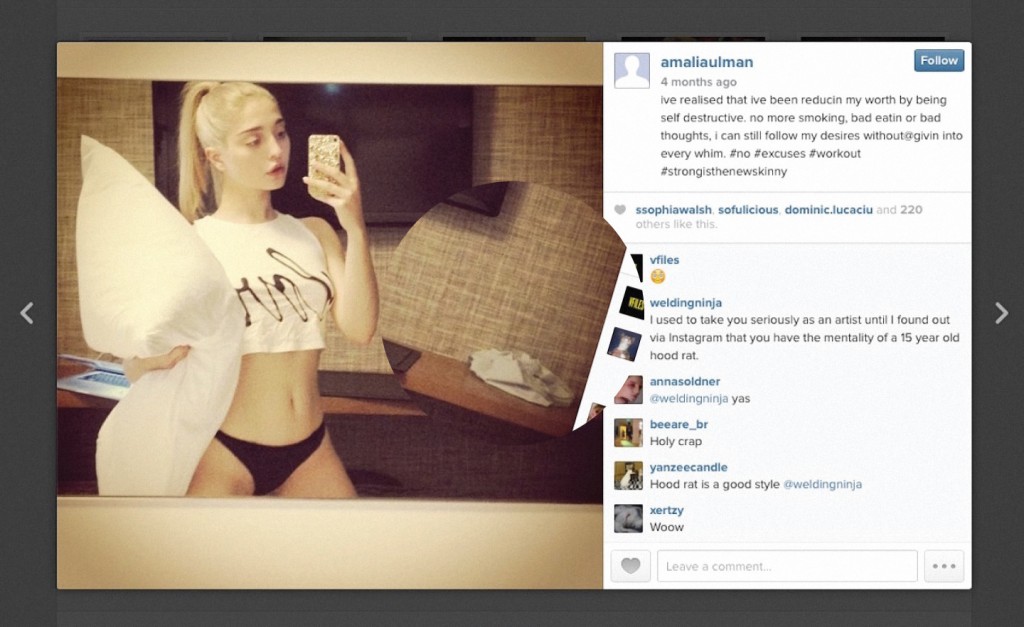

Argentinian performance artist Amalia Ulman has hijacked Instagram as her creative narrative form of choice. In the conceptual performance she calls “Excellences and Perfections” she has fabricated an Instagram feed that tells the story of a woman who has just moved to L.A. to try and become a model. The feed of photos chronicles her slow arc into what Ulman calls “middle brow femininity.” This essentially constitutes girls commonly referred to as “basic” or average in their tastes which include, but are not limited to, working out, yoga, Starbucks, quinoa, etc.

This ties in with our work on autobiography and the tension between self-representation and identity construction. With Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, we have never before existed in a time with so much opportunity for this kind of hyperreal and relentless identity construction. Instagram can almost be likened to the many frames of the self like the comic book form afforded for Spiegelman in Maus. But once we construct something, does it cease to be true from the nature of constructing it?

By Ulman creating this account that “passed” as real, she is drawing attention to the manufactured nature of our social media “selves” as such. The ambiguity of “truth” makes us pause on our own tenuous identities. We are mutable, formable, and pictorial artifacts of ourselves. Thus, as Friedlander asks, how do we navigate the “dilemma of wanting to engage in the culture of self-representation online without creating a fallacious fantasy image?” But, my question is, isn’t self-representation always a fantasy image just by the very nature you you having to imagine it and construct it for yourself in the first place?

To-reimagine something and conjure up its memory, is an act of creation itself. As we have seen in Stories We Tell, the past is composed and manufactured upon recall. Ulma’s project brings focus to the problem of “the real” assumed in autobiography. Even if we can never truly achieve a “true” account of “what happened,” how can we tell a story that is still important to tell?