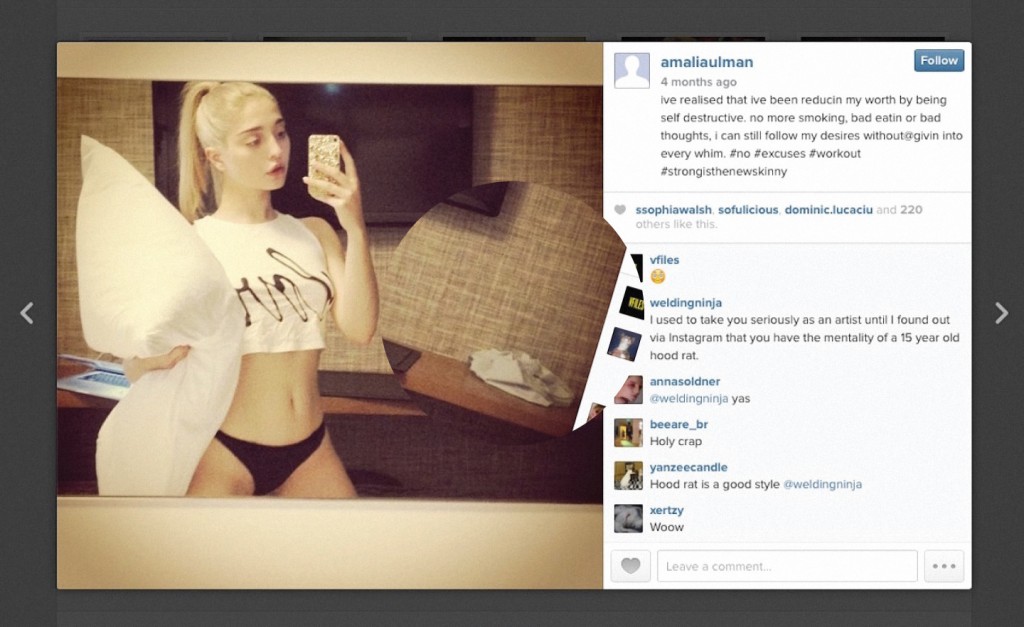

Argentinian performance artist Amalia Ulman has hijacked Instagram as her creative narrative form of choice. In the conceptual performance she calls “Excellences and Perfections” she has fabricated an Instagram feed that tells the story of a woman who has just moved to L.A. to try and become a model. The feed of photos chronicles her slow arc into what Ulman calls “middle brow femininity.” This essentially constitutes girls commonly referred to as “basic” or average in their tastes which include, but are not limited to, working out, yoga, Starbucks, quinoa, etc.

This ties in with our work on autobiography and the tension between self-representation and identity construction. With Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, we have never before existed in a time with so much opportunity for this kind of hyperreal and relentless identity construction. Instagram can almost be likened to the many frames of the self like the comic book form afforded for Spiegelman in Maus. But once we construct something, does it cease to be true from the nature of constructing it?

By Ulman creating this account that “passed” as real, she is drawing attention to the manufactured nature of our social media “selves” as such. The ambiguity of “truth” makes us pause on our own tenuous identities. We are mutable, formable, and pictorial artifacts of ourselves. Thus, as Friedlander asks, how do we navigate the “dilemma of wanting to engage in the culture of self-representation online without creating a fallacious fantasy image?” But, my question is, isn’t self-representation always a fantasy image just by the very nature you you having to imagine it and construct it for yourself in the first place?

To-reimagine something and conjure up its memory, is an act of creation itself. As we have seen in Stories We Tell, the past is composed and manufactured upon recall. Ulma’s project brings focus to the problem of “the real” assumed in autobiography. Even if we can never truly achieve a “true” account of “what happened,” how can we tell a story that is still important to tell?

Loved this post, Callie! Although I can’t remember if we discussed this in class at the beginning of term, this really reminds me of the work of performance artist Nao Bustamante. She made this audition tape: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZYpTlDfw8I in an attempt to become a contestant on the absurd reality television show, Work of Art. In the tape it becomes clear that Bustamante has– in a similar way to Ulman– created a fictional character in order to prove a point (or several). Bustamante plays on stereotypes of the feminine body, particularly one of Hispanic descent in the United States. She troubles the societal implications and expectations of these cultural stereotypes. Apparently not getting the joke– as seems often to be the case with this sort of performance piece as indicated by the first commenter on Ulman’s post shown above– she was accepted onto Work of Art and continued to challenge the assumptions made about the meanings and uses of “art” throughout her appearence.

I have seen this video and I found it hilarious. Great social commentary via humor. My favorite line is “I’m an object” and also when she comes to the workout session in a full black body suit.

This phenomenon is certainly not unique to Instagram! A couple of years ago (probably when we were both pre-teens?) a youtube account called lonelygirl15 (https://www.youtube.com/user/lonelygirl15) emerged, capturing people’s attentions as candid videos, but actually turned out to be fictional. Your post also reminded me of the Berenstain Bears spelling effect (http://mandelaeffect.com/berenstein-or-berenstain-bears), though I would say that’s less related.

I would say that given Whitlock’s conception of autobiographical truth, there’s of course no way to not be autobiographical even when a forgery is happening. I’d say that looking through Ulman’s Instagram as a viewer and user of Instagram, I’m weirdly offended by it. I think partly it’s because the “basic bitch” white girl trope, the “middlebrow femininity” this account tries to construct reeks of appropriation of black culture (re: “basic bitch,” “bae,” twerking, etc), filtering into palatable white femininity and consumerism.

I think the way Instagram allows a consistent way of creating a certain aesthetic makes the construction of this offensive representation (in my opinion anyhow) especially powerful. Each image makes me cringe louder than the next. I’m simultaneously reminded how much I would despise someone who – apparently – actually live and represent themselves this way, and how I am skeptical of Ulman’s creation of ‘fantasy.’

Hello!

From Ulman’s testimony on the project, I think “the cringe” is exactly what she is trying to enact. She is trying to be a mirror to a large number of people on Instagram who do enact this type of “basic” femininity.

I think she is trying to critique the palatable white femininity and consumerism that you suggest.

Very interesting post Callie! I agree with you that “the real” and representation perhaps can never be distinct from each other. This makes me think about how we represent our identities through media also influences how our memory is shaped by those events, making these representations seemingly real in a sense. In an interview with Sarah Polley, she states “Another thing that was really fascinating to me was that as my dad started writing the story, and then my biological father started writing his version of the story, and then I was thinking about making a film about it—the telling of the story changed the story itself.” The real and represented always seem to be changing in relation to each other. I think our online selves that create is a powerful example of this!

I really like your comment “the real and represented always seem to be changing in relation to each other.” It really turn the directionality of self-to-media into media-to-self. How do our online selves effect or non-online selves?

I find this art piece extremely interesting. Instagram seems to be one of the prime tools for creating a flattering self-identity. I have found that even more than Facebook and Twitter, it really encourages its users to create a perfectly curated self. For example, I find on Facebook and Twitter, people are more open to discussing different aspects of their lives that may not always seem as perfect. For some reason the actual way that Instagram functions really encourages this specific type of perfection. The ability to use filters to make something even more flattering or appealing and the visual nature of Instagram calls for topics that focus on beauty. Trends such as fitness pictures, food pictures, and style photography dominate Instagram even more than Facebook and other social media sites. Perhaps this is because it is a forum to share photos specifically, or perhaps this is something that naturally happened that was not initially intended. Either way, Instagram really highlights these needs to have a space to develop these idealized ideas of ourselves.

I definitely agree that Instagram is more aimed towards aesthetic perfection of a life as opposed to other media outlets. I wonder what kind of standards or aspirations that creates.

I think it’s very valuable to consider Instagram as medium of expression of creativity – beyond choosing a filter for your lunch pic. It has great potential to communicate a narrative to an infinitely large audience almost instantaneously, I personally have never encountered this type of storytelling so to speak on the app. It could be compared to the narrative presented in the Ai WeiWei exhibit in the sense that the “author” has full control over what is shown, what is not shown as well as chronology. They are able to communicate a story using very limited linguistic cues.

In response to your question I agree that any form of self-identity creation necessarily includes some level of what could be called “fantasy”. Each person’s understanding of their personhood varies from how they are seen by others, which was demonstrated in the multiple perspectives presented in the The Stories We Tell. But I would not discount this conceptualization of oneself as non-authentic based on it’s subjective nature. As seen in The Stories We Tell, it is the intertwining of these various and conflicting standpoints which provide a rich account of any individual identity.

Interesting, so it’s almost as if Facebook and Instagram are not us trying to articulate ourselves to others, but a fantasy of ourselves to ourselves. Perhaps authenticity in that case is not the goal, and self-expression is.

It’s pretty difficult just to define what kind of story is an important one. Say that someone tells their life story exactly as it is, with a non-biased documentation of every moment of their life, and presents it to the public. They might believe that the story of their life is a very important one and something that others should and will resonate with. However, even that thought in itself is rather self-pampering. The role of social media in people’s lives allows them to create a certain image for the public to gawk at. The image might be based completely on true facts but it might only represent the positive aspects of the individual. It can’t be called a lie exactly as they might not be broadcasting that the image being displayed is exactly who they are. They provide the most basic blueprints and the viewer fills in the blanks with their own imagination. Just the act of expressing various snippets of one’s self and day-to-day activities is enough to allow them a means to write a story with them as the protagonist, perhaps creating a certain sense of control and authority over the otherwise uncontrollable rollercoaster of their life.

“Looks nice! I like this image!”