- Do an end-of-year reflection. This is your last blog! What stands out for you from the year? What are your parting thoughts?

As the school year draws to a close, I am entering a stage of reflection for all of the unique experiences I have gathered thus far as a first year student at the University of British Columbia. Overall, when evaluating how my first year went, there are notable changes that are immediately distinguishable as meaningful adjustments to my life: moving into residence, playing my first year of soccer at the university (and the difficulty that came with nursing an injury), as well as all the newfound relationships that I was fortunate to make along the way. From an external perspective, my academic experience truly felt like a blur; syncing myself to the workload and classroom expectations took some serious acclimatization, particularly due to my previous school year which had dampened the intensity of the assignments (because of the pandemic’s influence).

In all honesty, I remember feeling unreservedly intimidated after the first few weeks of schooling; I didn’t properly know how to engage in the scholarly conversation and I frequently found some of the various readings across the CAP stream to be quite difficult. In addition, I had this overriding sensation that I was the only one feeling these insecurities and that everyone else in the stream was fully accustomed to the novel duties as a first year student. I vividly remember feeling like I was on a roller coaster of responsibility, having either just completed an assignment (or exam), or just beginning the process of starting out on another one. At first, this sensation was overwhelming and finding the right balance between the contrasting aspects of my life was hard to maintain.

However, as with most challenges, over time they become easier. I soon gained invaluable tactics that I had not previously learned to deploy in high school. The likes of calendars, pro-active emails and scheduled study sessions helped greatly in my overall ability to communicate and organize my schedule. I found with more experience, I was able to comfortably engage in a broad variety of topics throughout the scholarly conversation. I enjoyed the fact that ASTU was a year round course, as I felt that it allowed me to establish myself as a student with a voice and become educated about the required responsibilities of the course. Furthermore, I found the learning pod process to be enriching, as it not only allowed for deeper discussion on the chosen topics, but it also provided a space for me to assess how other students were managing with similar responsibilities (forming connections through relatability). Through these natural processes, all aspects of my life seemingly clicked, and the process became much more enjoyable and manageable.

Overall, I thoroughly appreciated my first year experience at UBC. I underwent the common process of situating myself to a new environment, and over time my routine grew instinctive and felt rather engaging. The most enriching part of the journey was the sensation of rising to the challenge and thriving. It delivered a sense of security that I didn’t initially possess, proving that growth does occur when faced with a tough challenge. In addition, the demands of this first year has personally newly installed a fundamental ability to manage time to a greater extent; a skill which will presumably be very valuable to have in the future. I am grateful for all of the experiences and connections I have made thus far, and I am truly excited for the years to come at this wonderful university.

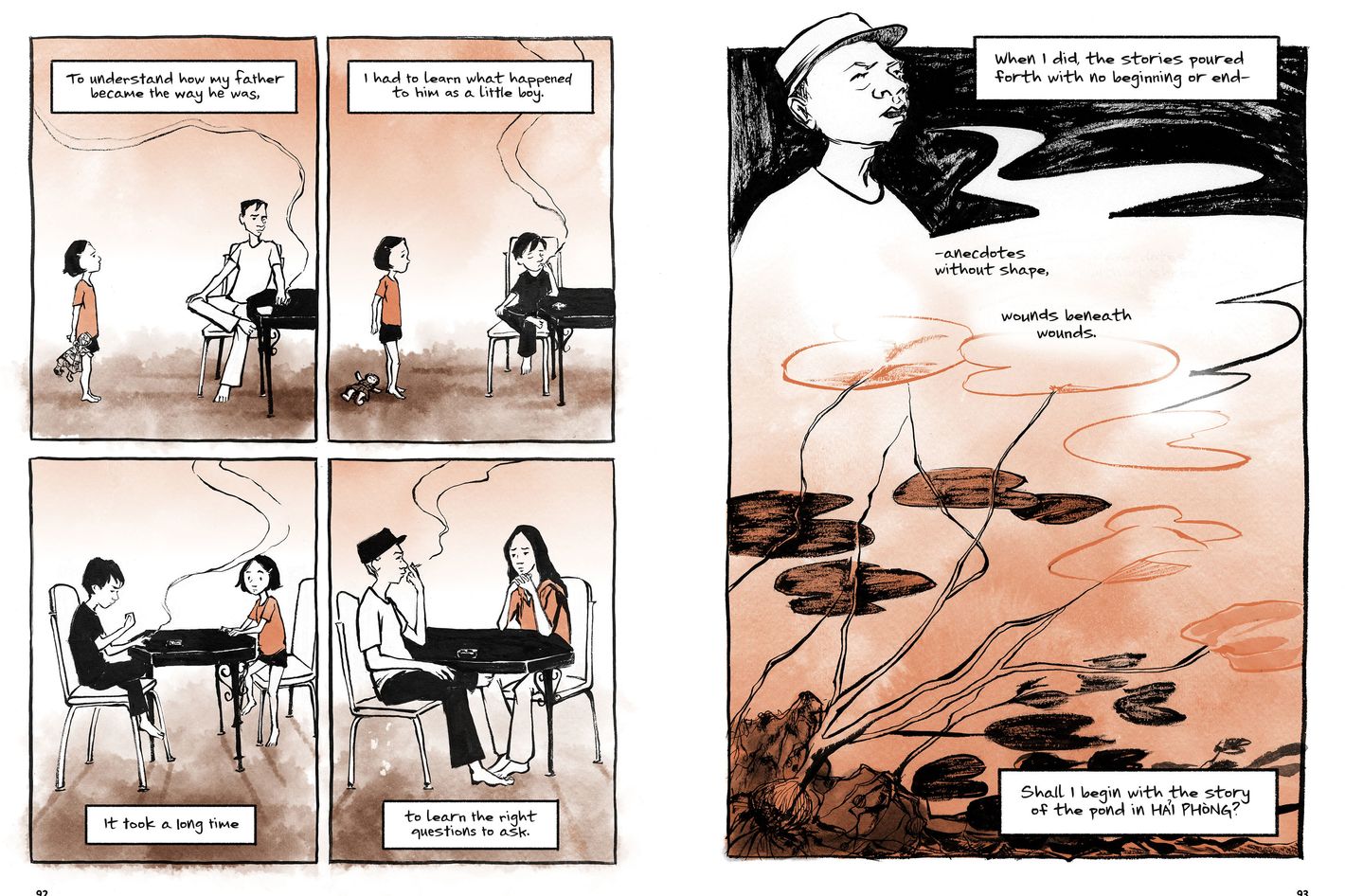

(Above: Body of Alan Kurdi, a Syrian toddler who sadly died as a refugee trying to flee his homeland (https://www.npr.org). The boat that Kurdi was on capsized on its way to the Greek Island of Kos. This famous image of Alan is known to be a key factor into why Hosseini made the “Sea Prayer” video).

(Above: Body of Alan Kurdi, a Syrian toddler who sadly died as a refugee trying to flee his homeland (https://www.npr.org). The boat that Kurdi was on capsized on its way to the Greek Island of Kos. This famous image of Alan is known to be a key factor into why Hosseini made the “Sea Prayer” video).