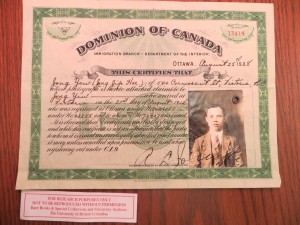

This is a head tax certificate. These certificates are a result of the 1885 Chinese Immigration Act passed in the Canadian legislature after lobbying by the Province of British Columbia. The Act required anyone of Chinese descent desiring to enter Canada initially to pay the amount of $50 for entry into the country, the exceptions being for diplomats, government officials and their entourages, and students (Asian Law reference). The amounts were increased to $100 in 1900 and $500 in 1903, which amounted to a hefty two years wages of a Chinese labourer (CNCC, Parliament of Canada). In 1923 the head tax was replaced by the Chinese Act on Immigration, which altogether prevented Chinese immigration to Canada. This act prevented family reunification resulting in a bachelor culture of Chinese men in Canada, which later caused a number of social ills such as opium houses, and starvation of separated family in China (CNCC). Yet in all of these circumstances, it is really the underlying ideologies of fear and ingroup-outgroup dynamics that drove the progression of exclusion of the Chinese. I will specifically examine the physical artifact of the head tax certificate and explore how fear discourse was institutionalized and self-justifying through the legal system.

Historical context

The historical context for the situation came from the mid-1800s when Chinese people, especially from Guangdong Province in south China, were looking for opportunity in the midst of a bleak-looking future in China. China had just recovered from the domestic Taiping rebellion that started in 1850 and was quelled only 6 years, throwing the country into disarray. Guangdong was particularly hit by additional factors, including significant imports of British goods resulting from the forced opening of treaty ports as demanded by the British and French as conditions for winning the First Opium War in 1842. The large quantities of imports destabilized the livelihoods of many Chinese, causing unemployment. Compounding these factors was that population growth had also exceeded food production causing further challenges for food security. The combination of these factors led many Chinese to seek for hope, and hearing the rumours of gold in Western North America, many decided to make the journey across the Pacific to make a go at a fortune. Many of these Chinese immigrants to Canada ended up working in labour intensive sectors, particularly the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), which was constructed from 1881 to 1884, during which 15000 Chinese immigrated to Canada and approximately 6500 Chinese workers worked for the CPR (CCNC). The completion of the railway left a vacuum in the labour demand and the Chinese who had migrated to different avenues of labour. These workers were often willing to work for much less than Canadians of European descent. The high labour supply to demand ratio functioned to create tensions in European Canadians who perceived that Chinese immigrants were taking their jobs, and so shortly after the CPR railway completion, the head tax was enacted as a deterrent to further Chinese immigration. The anti-Chinese discourse began several years earlier however, and perceiving Chinese as outgroup, inferior or even vilifying them was already in the public discourse.

Perceptions

Yet one element to observe in this history is that even though there were economic considerations, it was really the perception that Chinese immigrants would be taking away jobs from European Canadians that was the dominant factor in the outcome – ultimately, the issue revolved centrally on the fear of perceived compromised security to European Canadians, and it was this perception that motivated the political measures taken by the BC and federal government to act. The believed remedy to the situation was to minimize Chinese entry into the country and so the discourse was constructed to institutionalize inferiority of the Chinese. The result was legal structuring that functioned to normalize and perpetuate racist notions.

Any qualms that European Canadians may have had in constructing the Chinese immigrant as an outsider and inferior may have been justified through the institutionalizing process – the discourse was made so commonplace and authoritative through government publications that it was easy to go with the trend.

Interestingly, even though the head tax had initially functioned to restrict Chinese immigration with its first cost of $50, it was later increased. This feature further suggests that it may not have been primarily economic concerns that drove the increases in head tax prices but rather ideology, that European Canadians simply did not want any additional Chinese in Canada. These ideologies may be a combination both of the perceived labour security threat and ingroup-outgroup dynamics.

Constructed elements in the head tax medium

We next turn to examining the physical features of the certificate and what metadiscourse can be drawn from its characteristics.

The head tax certificate itself is a fully authoritative document issued by the Dominion of Canada, and grants the perceived legitimacy of the discourse of constructing Chinese immigrants as outsiders.

Like similar documents issued by the state, they were produced en masse. Notice how there are the blank spaces to be filled in – these intended blank spaces show the assumption that many of these documents would be filled, and the magnitude of this enterprise works as a self-justifying system: when a system operates at a large-scale, it can suggest it is more widely accepted, and, for those who contest the system, the large scale presents itself as a large obstacle to surmount. Compare for example if The head tax receipt had been done as merely a provisional arrangement, on unofficial paper, but the use of the official stylistic Canadian document legitimizes and institutionalizes the agenda of creating the Chinese as the other and inferior.

We notice also the language employed in the certificate. One of the lines in the certificate includes a blank space for the immigrant’s name and then states “claims to be” followed by another blank space. This curious wording hints at something deeper, that there is an implied burden of proof on the immigrant to prove their identity, almost as though it is officially assumed that the Chinese newcomer would attempt to pose as another. The language then works as a further element to institutionalize the Chinese as suspect, furthering the discourse of fear and reinforcing the resolve to maintain Chinese immigration at bay for the sake of perceived security.

Another aspect to consider was the use of the head tax certificate as identification for Chinese migrants. There is a political connotation in doubling up the head tax certificate with an identification component because it implies that the immigrant’s identity is connected to their payment of the tax – the head tax payment was already a physical manifestation of European Canadians viewing Chinese people as “the other”, and then placing the their identification in conjunction with the certificate further reinforced the otherness of the immigrant. The tax set apart the Chinese person already as having to arrive by a kind of concession and yet having the identification card connected to it functioned to recall the immigrant’s admission to the country under special circumstances. Further, the requirement of a photo can be seen as somewhat criminalizing – although it could be justified that one needed a photo to confirm that the certificate was purchased for this, yet other receipts generally did not carry a photo on it. The certificate could have been a paper without a photo – it is as though the certificate photo interaction were to function as a persistent and subtle reminder to the unfortunate immigrant that he was not preferred here.

One can also see the hard edges of this policy. The borders of the document are designed not only for embellishment but to deter and hinder forging of the document, demonstrating the level of serious commitment of the Canadian government to enforce this policy, that this was not simply catering to the desires of BC lobby groups but full federal agency was involved.

Overall, the head tax certificate subtly but certainly demonstrates the fear of European Canadians regarding loss of security through losing work. Through a number of physical details including the language, the borders, the anticipation of wide usage, the photo, and identification components, it was designed, perhaps intentionally, to normalize and justify the anti-Chinese immigration actions taken as were thought to prevent injuring domestic interests. The head tax receipt is another interesting example of how media captures a thought and expresses it through all the physical factors of the document itself.

This head tax certificate is part of the Chung Collection at the Rare Books and Special Collections at the Irving K Barber Learning Centre. The collection was donated by Wallace Chung, a Chinese Canadian who donated a substantial collection to UBC libraries. The collection contains around 25,000 items, including Canadiana, CPR artifacts, records of early Chinese immigrants to BC, European traveler’s logs, ship dining utensils, photographs, amidst other myriad artifacts.

Works Cited

“CCNC : Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act.” CCNC : Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act. Web. 23 Apr. 2015. <http://www.ccnc.ca/redress/history.html>.

Hansard. “38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION.” PARLIAMENT of CANADA, * Table of Contents * Number 084 (Official Version). 18 Apr. 2005. Web. 23 Apr. 2015. <http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=1659497&Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=38&Ses=1>.