2] In this lesson I say that it should be clear that the discourse on nationalism is also about ethnicity and ideologies of “race.” If you trace the historical overview of nationalism in Canada in the CanLit guide, you will find many examples of state legislation and policies that excluded and discriminated against certain peoples based on ideas about racial inferiority and capacities to assimilate. – and in turn, state legislation and policies that worked to try to rectify early policies of exclusion and racial discrimination. As the guide points out, the nation is an imagined community, whereas the state is a “governed group of people.” For this blog assignment, I would like you to research and summarize one of the state or governing activities, such as The Royal Proclamation 1763, the Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, or the Multiculturalism Act 1989 – you choose the legislation or policy or commission you find most interesting. Write a blog about your findings and in your conclusion comment on whether or not your findings support Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility.

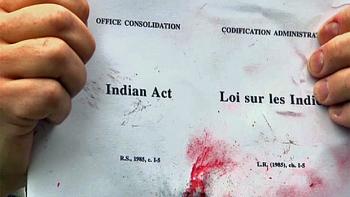

(I think that this is a really powerful photo!)

(I think that this is a really powerful photo!)

The Indian Act (1876), according to UBC’s Indigenous Foundations website, is a “federal law that governs in matters pertaining to Indian status, bands, and Indian reserves” (Indigenous Foundations n.p.). Although the Indian Act was developed in 1876, there were other legislations that pertained to the governing of First Nations people prior to its conception. The Indian Act is a direct result of the combining of two previous legislations, The Gradual Civilization Act (1857) and Gradual Enfranchisement Act (1869) (Indigenous Foundations, n.p.) Both legislations were created with the intent of enfranchising First Nations people into Canadian settler society (a society, as we read in the Can Lit Guide, that was colonized and promoted as an extension of British society).

The Indian Act sought to legally identify those FIrst Nations under “Indian status.” This was done through an exclusionary gendered practice. As the Indigenous Foundations website notes, “the Indian Act defined ‘Indian’ as:

First. A male person of Indian blood reputed to belong to a certain band;

Secondly. Any child of such person;

Thirdly. Any woman who is or was lawfully married to such person” (Indigenous Foundations qtd Indian Act n.p.).

This is an extremely important note, not only because its sexist in its nature, but because it points to the fact that the government knew it could control the legalities around the who was a status Indian, therefore limiting their number in the Canadian population, slowly assimilating them into Canadian society.

Status was being carried down through the men’s line, which deprived and dispossessed many women of their rights as Indians and their rights to live on their reserve lands. These rights were also lost for their children as well. Moreover, if we think about how people were socialized during this time, many white women did not want to marry Indian men. As Frye mentions, there was the creation of second class citizens (Frye xxvi). This is supported by the Can Lit Guide as well, “early radicalized settlers and later immigrants were seen as less worthy, and therefore less Canadian” (Can Lit Guide, n.p.). White, in Canada, was preferred, and many First Nations people lost their legal rights because of the intermarriage between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Not only did the Indian Act assimilate peoples through their commitment to their partners, but it had also put in place the Indian Residential School system. This was an initiative to forcefully assimilate First Nations people into Canadian society, making the use of their languages, traditions, and practicing of cultures forbidden.

As for Coleman’s concept of the project of white civility, I do believe that the Indian Act was put in place to diminish the population of First Nations in Canada. It was an act that was in place for a legal assimilation through force and through family.

Frye mentions the idea of unity and identity (Frye xxii). He writes, “Assimilating identity to unity produces the empty gestures of cultural nationalism; assimilating unity to identity produces the kind of provincial isolation which is now called separatism” (frye xxiii). This can be related to the Indian Act. It was a piece of legislation that sought to define what an “Indian” is and assimilating those who did not fit the legal category. He continues, “Real unity tolerates dissent and rejoices in variety of outlook and tradition, recognizes that it is a man’s destiny to unite and not divide, and understands that creating proletariats and scapegoats and second-class citizens is a mean and contemptible activity” (Frye xxvi).

Bibliography

“Enfranchisement.” Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

Frye, Northrop. The Bush Garden Essays on the Canadian Imagination. Concord, Ont.: House of Anansi, 1995. Print.

“Guides | CanLit Guides.” Guides | CanLit Guides. Can Lit Guides, 2013. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

Hanson, Erin. “The Indian Act.” The Indian Act. Indigenous Foundations, 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

“Indian Act.” Photograph. rabble.ca. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.