Much of Chamberlin’s book spoke of colonization in Canada. As I have written on two different blog comments, storytelling has been a large part of First Nations traditions and cultures and now, in the face of settler colonialism, it is a form of resistance and resurgence. Here is a great article that discusses this process of decolonization with storytelling:

file:///Users/test/Downloads/19626-46035-1-PB.pdf

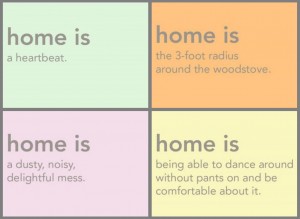

Also, a friend of mine’s blog. She’s Metis. This blog post she wrote is about redefining home:

https://halfbreedsreasoning.wordpress.com/2014/11/05/redefining-home-connection-place-and-belonging/

4. For Chamberlin, figuring out this place called home is a problem because, as he notes, he “doesn’t come from anywhere, except the Americas. And somebody else calls this home, somebody who isn’t happy having [him] around” (87). This is a difficult realization for anyone to grapple with when defining what ‘home’ is to them. This is especially true when Chamberlin speaks of the creation and telling of stories, whether to believe or not to believe them. For settlers in Canada, the conception of ‘home’ was built out of a false pretense about settling land. People used this pretense to believe that they were entitled to live on this land. In relation to settling Canada, Chamberlin notes, “We make homes for ourselves and drive others out, saying that we have been here forever or sent because of a vision of goodness or gold, or instructions from our gods” (2). This story of settling land for these reasons have been passed down from generation to generation, enticing their settler descendants to believe these stories as well, confirming their relationship and idea to what they identify as ‘home’.

However, stories that are told are not always automatically believed by the listener. It is said that “stories… have to do with belief; and belief involves a conflict between the true and the untrue” (Chamberlin 91). There are always contradictions in stories, such as the ones told by the settlers in Canada to justify their claiming of land. The listener is the one who must choose whether or not to believe the stories, ultimately making that story true to oneself. In terms of finding a place we call home, one must find a place that encourages stories and feelings of belonging, comfort, and reciprocity. As Chamberlin notes, “home is caught up in contradictions between reality and the imagination, here and elsewhere, history and hope. Many of us, from time to time, have probably felt lost and unhappy at home” (74).

It is also problematic to find home based on Chamberlin’s concepts of imagination and reality because, as he notes, both are “remarkably similar” (Chamberlin 125). He explains, “We learn how to live comfortably with both of them. We learn that neither is the true one, and that sometimes it isn’t easy to tell them apart. We learn that we often don’t want to, or need to, because the business of living in the real world depends on our living in our imaginations” (Chamberlin 125). In other words, finding home based on our imaginations and realities can not be accurate because our realities and imaginations may be convoluted, misleading us to believe false ideas of what “home” is. That is the place in which one does not find home.

Chamberlin points out, “The sad fact is that the history of settlement around the world is a history of displacing other people from their lands, of discounting their livelihoods and destroying their languages,” he also addresses another way of viewing this. He notes, “The history of many of the world’s conflicts is a history of dismissing a different belief or different behaviour as unbelief or misbehaviour, and of discrediting those who believe or behave differently as infidels or savages” (Chamberlin 78). These two visions of colonization are similar in that they have the same outcome, however, the storytelling of colonization is different. The first viewpoint is concerned with telling a story of domination, dispossession and erasure without really explaining how or why. The second, is a closer look into the justification of claiming lands for settlement. In regards to the settlement of Canada, I believe that the first story has the most consequence attached, with telling this version of history it focuses on the colonization process of acquiring lands and destroying languages and livelihoods without engaging with the most important reasons for how the colonizers justified those actions. It reduces the First Nations peoples to objects rather than the subjects.

Bibliography:

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Reimagining Home and Sacred Space. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2004. Print.

Nock, Samantha. A Halfbreed’s Reasoning. WordPress, 5 November 2014. Web. 16 January 2015.

Sium, Aman and Eric Ritskes. “Speaking Truth to Power: Indigenous Storytelling as an Act of Living Resistance,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2.1 (2013): 1-10. Web. 16 January 2015.

Willard, Wendy. “Home Is.” Image. WendyWillardBlog. Web. 16 January 2015.

Hi Laura, thank you for this interesting answer to my question. I will be interested to read your comments, and I have one suggestion for you; in order to encourage comments it is a good idea to end you blog responses with a question.

How to hypertext your urls. First, type a name or title for the link. 2] highlight the name or title. 3] go to the tool bar and click on the icon that looks like a chain link. 4] a box will pop up with a place to paste the url address. 5] click save and the name you highlighted will be the link. Good luck.

Thanks for the tip Erika! I will definitely use that in the next blog post.

And I will also start ending my blogs with a question, great suggestion for starting conversation!

Laura