Objects are being knocked down.

My elementary school for a glass and concrete institution,

The local restaurants in my neighborhood for big condos,

A standard work week,

My silence and compliance.

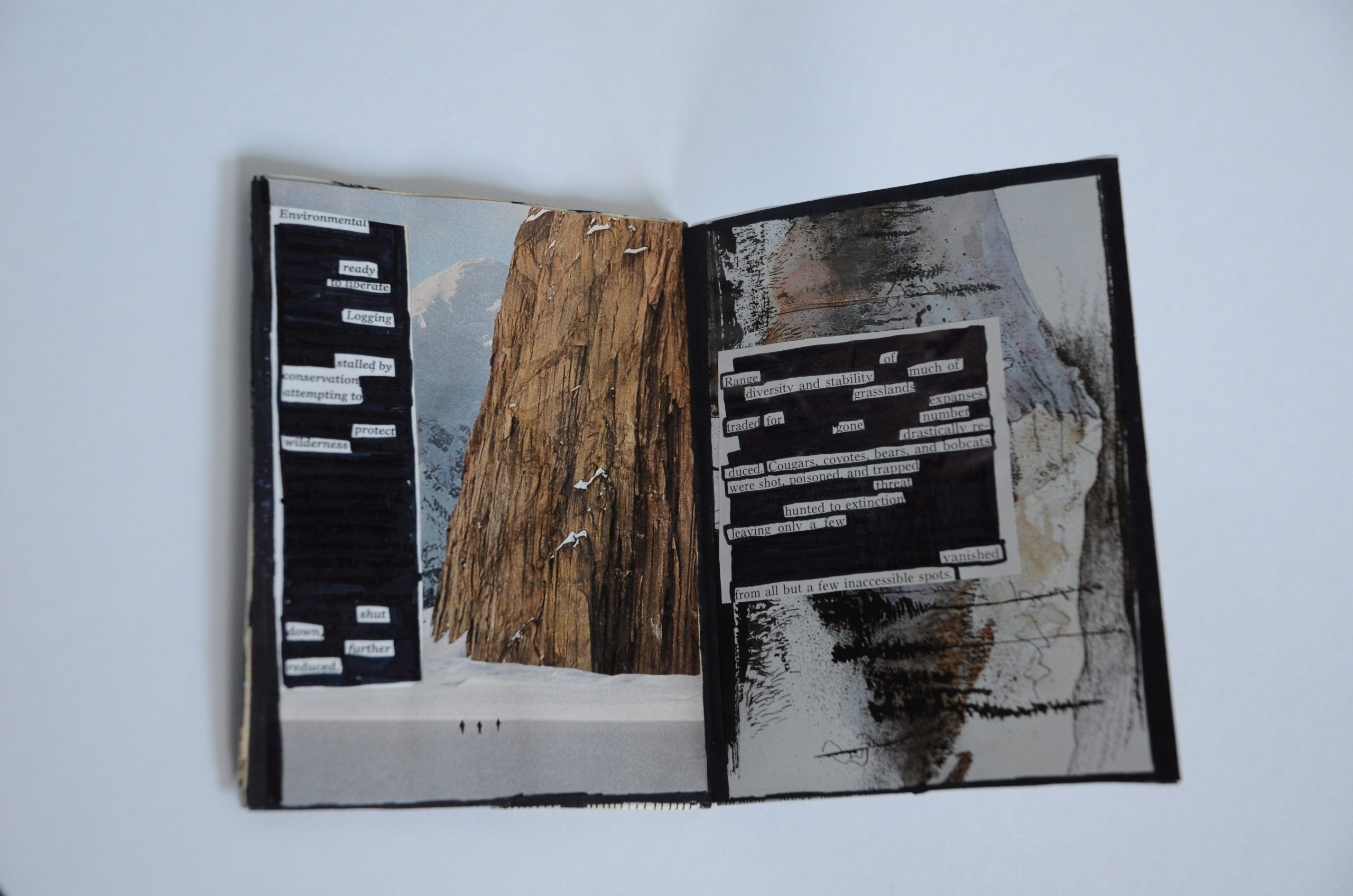

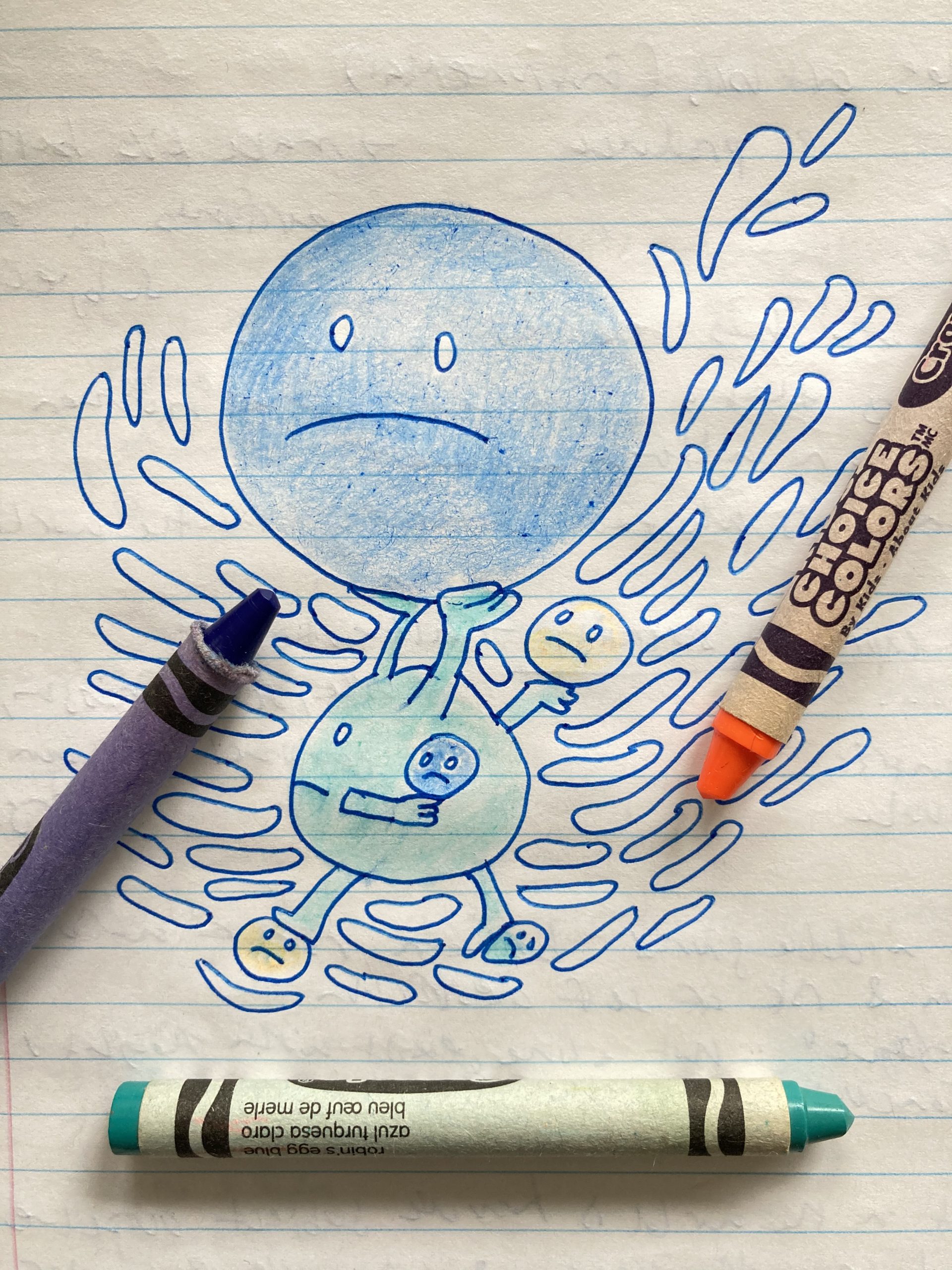

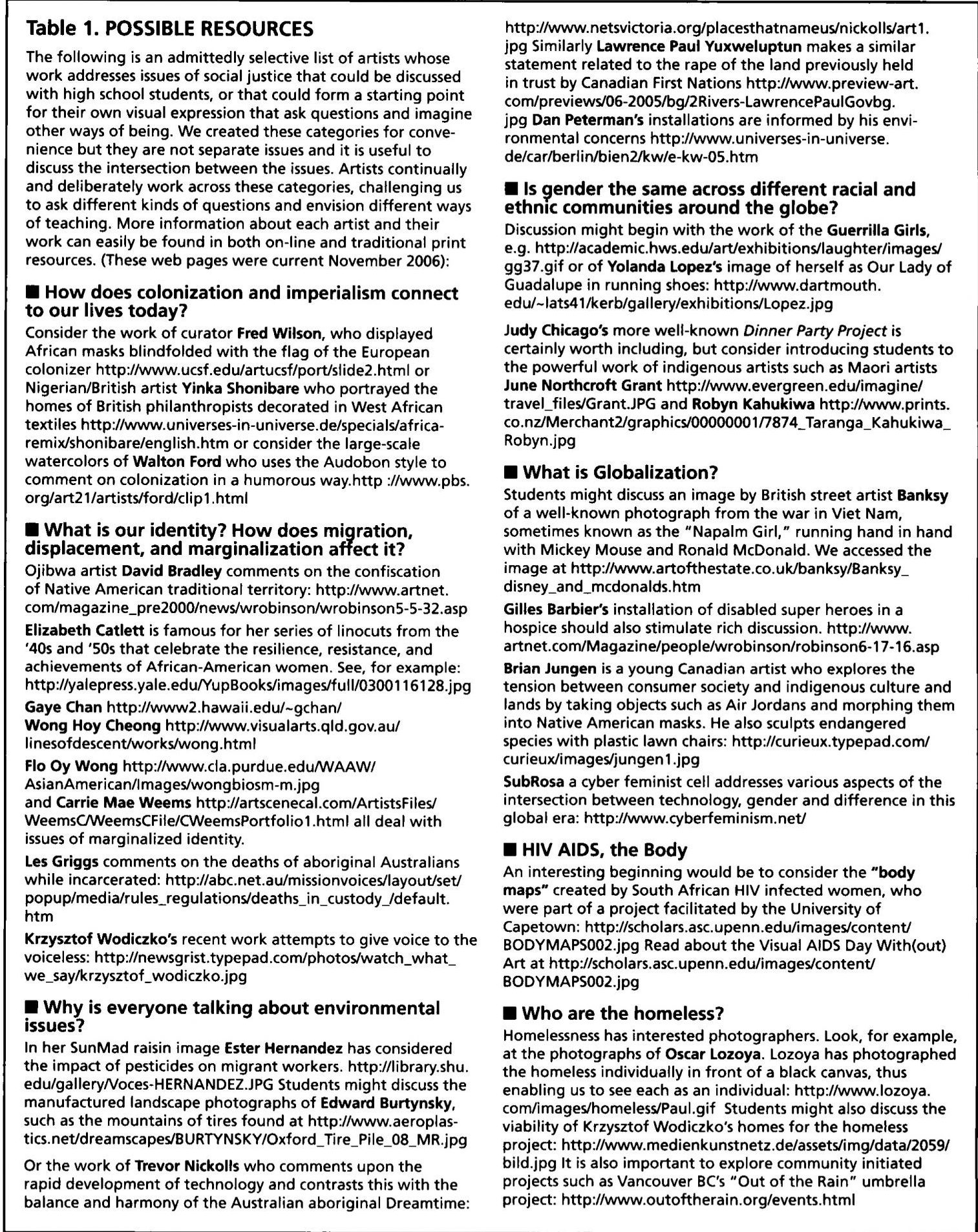

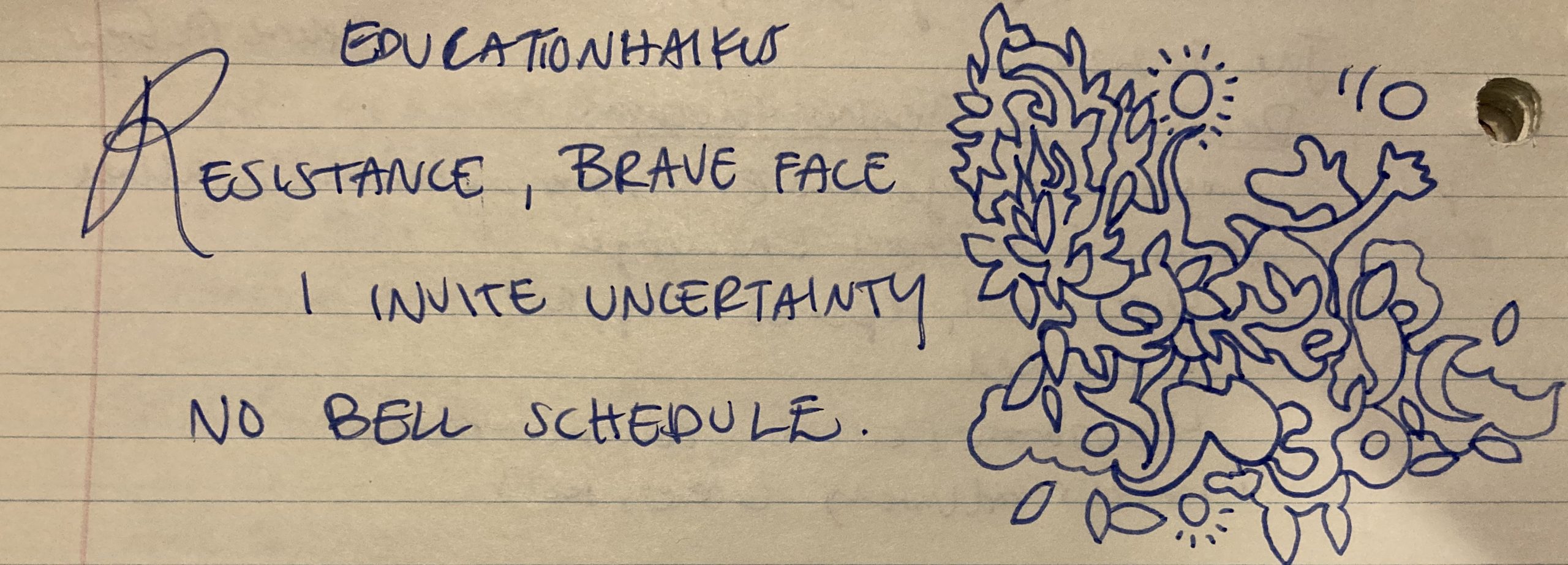

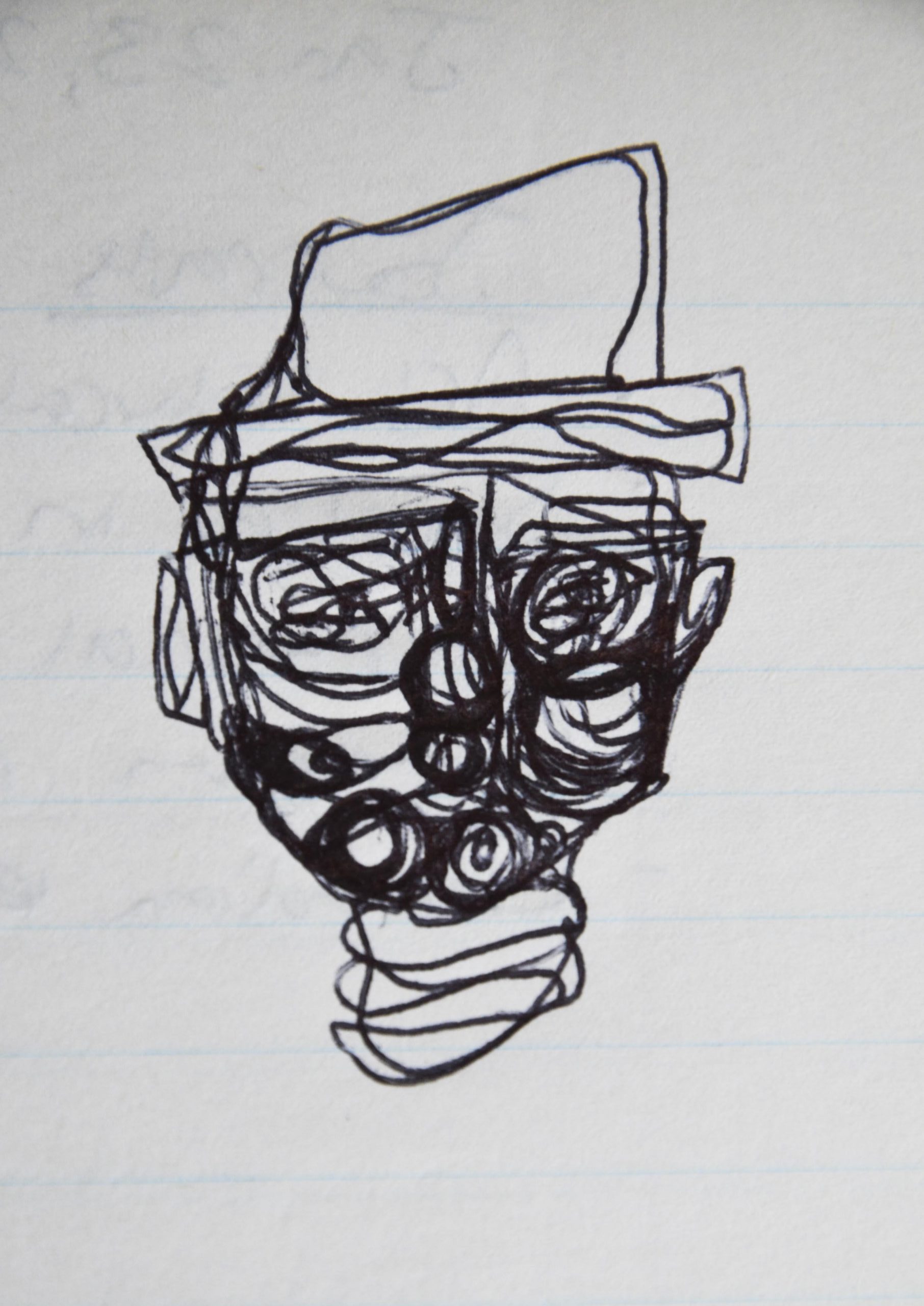

The world is always testing us. This year, it took a world-wide pandemic for people to break their nine-to-five work cycle, fast forward the future of education to a hybrid learning model and shake the city up to the point where they actually needed to care for the homeless. Black lives were and are at the disposal of systematic racism, brought to light by major protests across the world. Education has an increasingly important role to play amidst chaotic realities that lie just a few feet from the playground. As an art educator, I know that the arts are vital in guiding students through moments of fear, anger and doubt, as well as a force for change and growth.

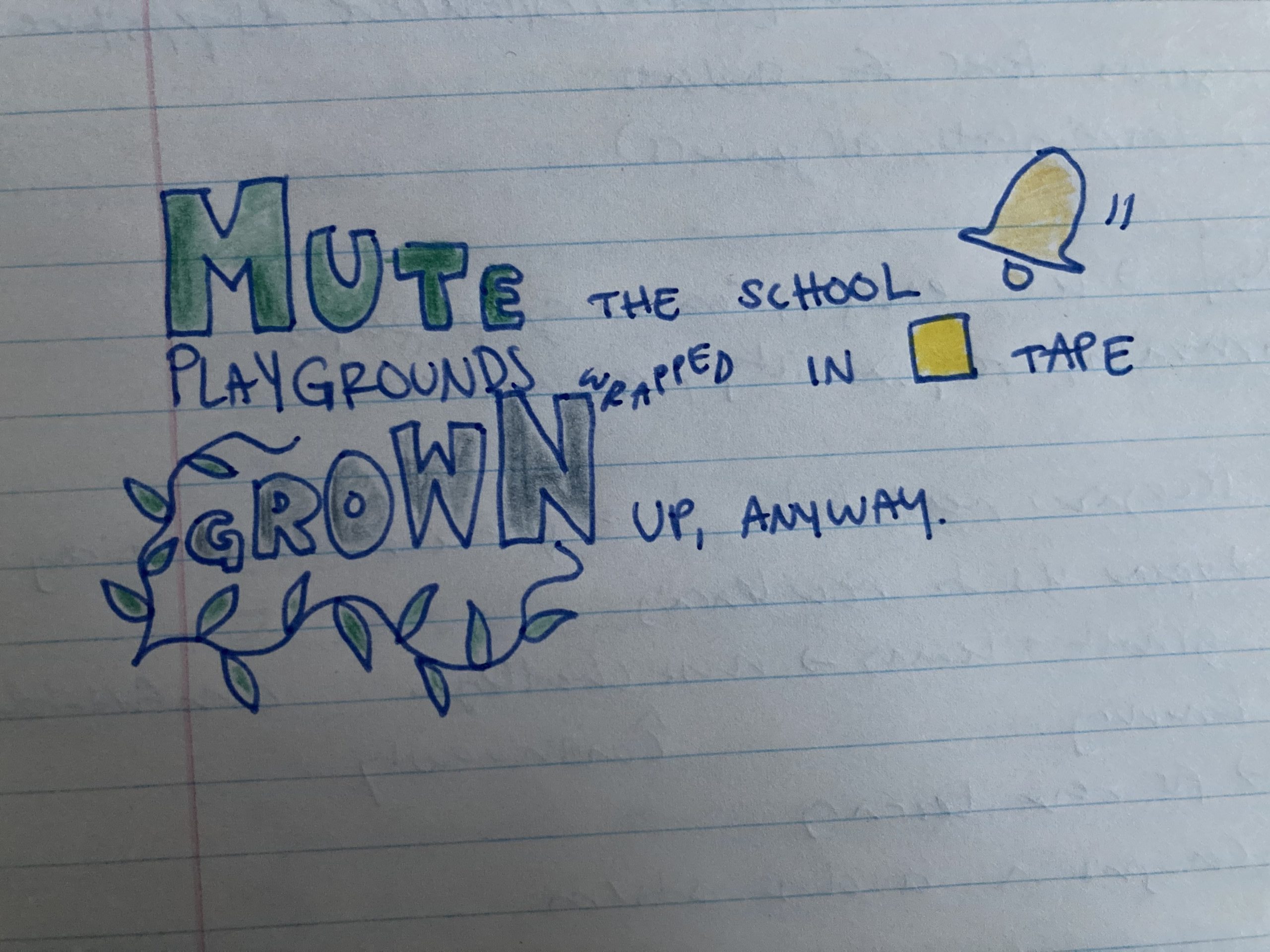

Art education is a critical practice of how society communicates, produces and revisits media. I will help students read the visual signs and develop their own. Drawing from contemporary art practices, I’ve come to see that art is political and created from experience. And thus, the final product of an art project can represent some form of activism. Ultimately, it is the internal change that occurs within my students that signifies learning (Biesta, 2012).

I am excited and scared to be an art educator during this time, but most of all, I feel hope. Art can teach students how to actively reflect on historical and current issues. Now is also the time for me to not exercise my authority as the expert (Britzman, 2003). I ask myself; What can I bring to arts education that technology can’t? Britzman says that education is a dialogical process involving an exchange between locations and people. As an artist and art educator I take on the role of the listener. As Desai & Chalmers (2007) suggest, I will open myself up to being honest and open to learning along with students, because these complex times necessitate collaboration and community more than ever.

References

Biesta, G. (2012). Giving Teaching Back to Education: Responding to the Disappearance of the Teacher. Phenomenology & Practice, 6(2), 35-49. [Online public access]

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice. A critical study of learning to teach. Revised edition. State University of New York Press.

Desai, D., & Chalmers, G. (2007). Notes for a dialogue in art education in critical times.

Art Education, 60(5), 6-11.