Postcard depicting Harrison Avenue in 1905. [Source: “Chinatown, Harrison Ave., Boston, Mass.” General Photographic Collection, Historic New England, 1905.]

Moy Ni Ding lived all of his Boston life at 23 Harrison Avenue. Although most of his early life remains undocumented, we know that Ni Ding was born in Taishun, China, probably in the first week of July (“Banquet”) 1857 and immigrated to Philadelphia in the 1870s before making his way to Boston’s Harrison Avenue (China Comes to MIT). Along with his steady residence, Moy Ni Ding appears to have had multiple businesses and stores scattered around Boston’s Chinatown. In fact, Boston newspapers from 1895 to 1931 refer to him alternatively as a ‘grocer,’ a ‘storekeeper,’ a ‘proprietor’ and a ‘restaurant manager.’

Despite his apparent prosperity, Ni Ding had several brushes with the law. In fact, his earliest mentions date back to 1895, when he was arrested on gambling charges while running a lottery out of his residence at Harrison Avenue. Ni Ding, along with possible kinsmen Moy Loy and Moy Jon Du, was accused of denying a Chinatown resident his due prize money. Ni Ding and Jon Du were fined $100 apiece, while Moy Loy was discharged from his position as an interpreter at the Boston Municipality (“The Moys and the Chins”).

Moy Ni Ding married twice. Little is known about either wife; like several other Chinese women of their time, their lives appear to be scarcely preserved. We know, through Edith Eaton’s journalism about the Moy family’s visits to Montreal, that the first Mrs. Moy Ni Ding was married in her late teens and bore their daughter, Ah So Non, sometime in 1894 (Eaton). The couple had their first son, William Moy Ding, in 1896 (“A New Baby”), and their second son, Moy Lung, in 1904. After the death of his first wife, Moy Ni Ding married Wang Shee in 1916. His second marriage took place by proxy in China, with a relative of the bride standing in as a representative for the bridegroom. The second Mrs. Moy Ni Ding traveled from China to Montreal in 1918, where the couple met for the first time. She entered Canada as the “wife of a Chinese merchant” (“Chinatown to Celebrate”), which exempted her from the Chinese Exclusion Act in place in the United States. In fact, Montreal was a bridge for the Moys’ passage to Boston; it was common, it seems, for couples to be married by proxy in China, and immigrate to Boston via Montreal (Eaton).

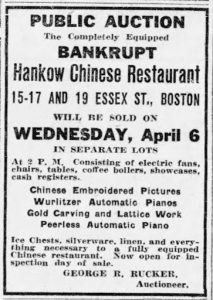

Hankow Auction Advertisement, The Completely Equipped Bankrupt Hankow Chinese Restaurant. [Source: The Boston Globe, 13 April 1921, p.21.]

Moy Ni Ding visibly rose in prominence in the Boston Chinatown community over the last two decades of his life. He was the owner of Hankow restaurant (often spelled Han Kow) on Essex Street, which was a widely popular joint in Chinatown. Han Kow, however, petitioned for bankruptcy in April 1921 and was sold in an auction (“The Completely Equipped”). Despite the bankruptcy, Moy Ni Ding continued to hold several titles within the Chinese community in Boston; for example, he was President of the Chinese Restaurant Association of New England (“Banquet”) and the founder of the Boston Chinese American Merchants Association, and he led the Chinese Boy Scouts at some point (China Comes to MIT). Ni Ding died in June 1931.

Moy Ni Ding’s elder son, William Moy Ding, appears to have held a particularly prominent position in the Boston Chinatown community as well. He was not only a popular student athlete, but also the first Chinese student in Boston to study in an English school (“Chinese Discovered America”). He was also the first Chinese student to be enrolled in MIT, where he pursued a Mechanical Engineering degree. In 1916, he married Rose Lee. Like his father, William Moy Ding served as the President of the Boston Chinese American Merchants Association, and also earned the title of ‘Mayor of Chinatown’ (China Comes to MIT).

William Moy Ding as photographed in 1915. [Source: “William Ding Moy ca. 1915 in Boston School Cadets uniform” by Beverly Wing, China Comes to MIT]

Works Cited:

“Our Model Tenements.” Boston Evening Transcript, 24 October 1906, p.17.

Boston Chinatown Atlas. 2012.

China Comes to MIT: MIT’s First Chinese Students/早期中国留学生: 1877-1931. 2017.

“Banquet to Moy Doy and Moy Ni Ding.” The Boston Globe, 7 July 1919, p. 16.

“The Moys and the Chins.”The Boston Globe, 06 April 1895, p.10.

“A Chinese Baby. Accompanies a Party Now on Their Way to Boston.” Montreal Daily Star, 11 Sept 1895, p.6.

“New Baby in Chinatown.” Democrats and Chronicle, 15 August 1896, p.5.

“Chinatown to Celebrate.” The Boston Globe, 30 April 1918, p.14.

“Throng Pays Last Tribute to Memory of Chinese Giant.” Boston Globe, 30 March 1920, p.7.

“The Completely Equipped Bankrupt Hankow Chinese Restaurant.” The Boston Globe, 13 April 1921, p.21.

“Chinese Discovered America, Barry Says.” The Boston Globe, 16 September 1916, p.16.