Last experience blog of the course!

When Jon asked us to discuss encounters, I thought of the moments when I tell people my name. Oftentimes when I tell someone my name is Cissy, I observe (since Jon wants these experience blogs to be more about observation) that they look confused for a second. At first I thought it was because my name is literally “sí sí” AKA “yes yes” in Spanish. (Apparently my name means “pee” in Cantonese so that’s great). But when I got to Pisac, I was informed by multiple people that sisi actually means “ant” in Quechua and people were surprised that I was named Ant. The other day, I found out the little black cat that we’ve encountered roaming around the cafes and botanical garden of Pisac is named Sisi! Just an interesting observation about names and their varied meanings.

Through the sickness and stress of the past few days, I’ve almost forgotten about the excitement of Inti Raymi! During the festivities in the Plaza de Armas, I think it’s interesting to note that I observed what was an extremely sunny day suddenly become cloudy when the Inca entered into the square. I don’t know what this indicates. Is it a bad omen? During the part at Saqsaywaman, I was nervous when I began to feel drops of rain. I thought, oh now this has to be a bad omen. Turns out I had nothing to worry about! I observed that each time an offering was made, the sun came back out, both during the offering of the chicha and the sacrifice of the llama. The sun came back so strong it was almost unbearable. What does this mean? Was the event timed to be this way? Was it a coincidence? Or was it something more?

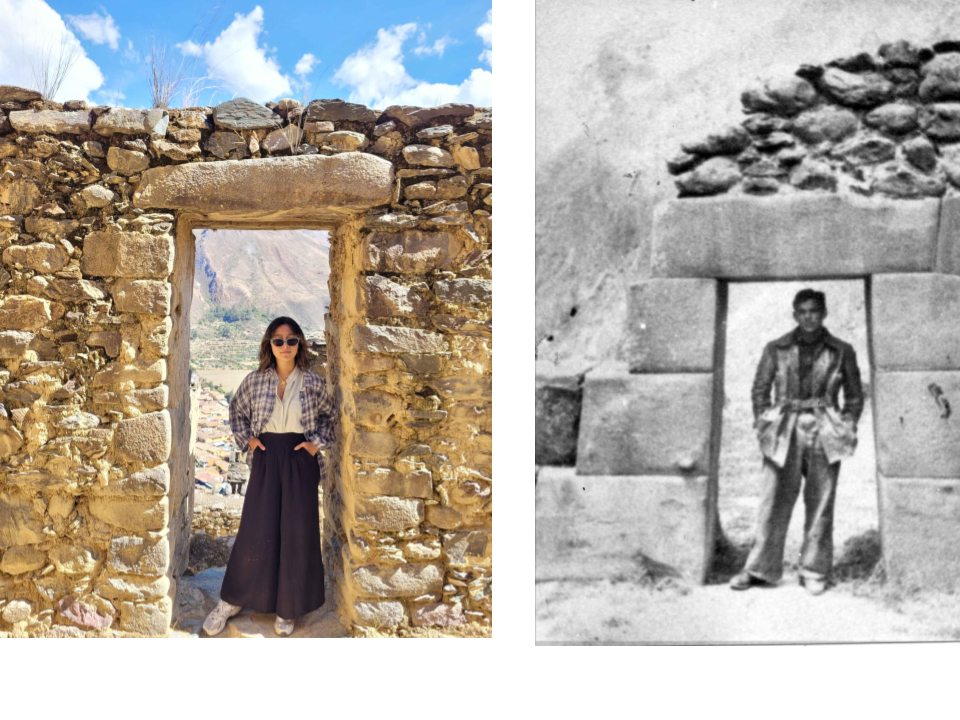

When we hiked up to the Pinkuylluna ruins on our last day in Ollantaytambo, our tour guide Jhon (Jon? John?), pointed out the sun temple of the Ollantayambo ruins on the mountains across from us. He told us that on the winter solstice of June 21st, which we had missed by a day, you would usually be able to see multiple rays of sunlight converging on the temple. But that wasn’t the case this year. Jhon said that this year, it was cloudy. I asked him what this meant. What did it indicate to the Incas if it was cloudy on the day of their most important celebration for their most important god Inti? Jhon said this never would have happened during Inca times; he said it was never cloudy on the winter solstice until recently. And it’s because of climate change. I don’t have the meteorology or climatology or atmospheric science background to explain why, but I do know that climate change leads to unpredictable changes in weather patterns.

Here, I observed how climate change disrupts Indigenous lifeways by disrupting ways of understanding and keeping time. It disrupts agricultural cycles, shifting times of sowing and harvest — knowledge which has been developed over countless years on the land and passed down through generations, and which now has to adapt rapidly to changing conditions. It disrupts what can grow on the land and when, especially as unpredictable rainfall forces farmers to choose drought-resistant varieties.

I’ve been listening to Lenin on loop as I write my position paper. In his song Nuestro Mensaje, I think he sings (I can’t find official lyrics), “Pachamama es la vida”. Pachamama is life. I think about that a lot.