In my ASTU 100 class we recently had the exciting opportunity to work in Rare Books and Special Collections here at UBC; an archive that contains “significant collections of rare books, archival materials, historic maps, photographs, broadsides and pamphlets” (rbsc.library.ubc.ca) focusing on British Columbia’s history. On our first day in the RBSC reading room we were encouraged to take a look at all of the archival material laid out in order to get a sense of what each collection was about. Though each collection I looked at was interesting and meaningful to the province’s history, the collection that I found especially intriguing was the Chung Collection.

This collection was gathered by Dr. Chung over 60 years, and includes archival material that pertains to “early British Columbia history, immigration and settlement, particularly of Chinese people in North America, and the Canadian Pacific Railway Company.” (chung.library.ubc.ca) Dr. Chung was able to collect over 25 000 items such as immigration papers and photographs, and then personally donated his collection to the UBC library so that “as many people as possible can have the opportunity to understand and appreciate the struggles and joys of those who have come before them.” (chung.library.ubc.ca)

The one piece of archival material that struck me the most from the Chung Collection was a red and green “royal tartan” journal that had a cameo of Queen Alexandra on the front. Among head tax documents and immigration papers, this item’s appearance was so distinguishably representative of English culture, and upon examining it’s contents, so was what was written inside. It contained pages of english handwritten letters that had been copied from correspondents between people of a high class in society. It included phrases such as, “Uncle George called last night and took us for a sleigh ride.” This line was found on a page in which the letter was written on the 20th of April 1902, and at the bottom was addressed from “your loving little girl, Melly.” The purpose of these journals were for Chinese people that had immigrated to Canada to learn english by copying letters in the journal, repeatedly. Often a letter was copied down 2, 3, sometimes 4 times.

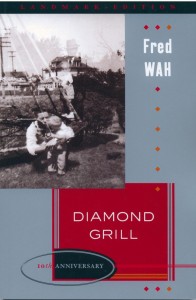

I found the initial juxtaposition bizarre; this journal that without any context would appear to be the possession of an upper class white person, along side collections of papers outlining the head tax and immigration. Considering Chinese immigrants to Canada in the early 1900’s faced such severe prosecution and racism, reading this journal that was written by Chinese person but contained content that was so remarkable ‘white’ was thought provoking. It reminded me of the idea in Fred Wah’s Diamond Grill, of “faking it.” Opposed to some of the examples in Diamond grill where “faking it” was more of an open “performance”, these journals could be considered a form of “faking it” because of the way in which they are an example of Chinese people being assimilated and indoctrinated into “Canadian culture.” Copying down the letters served as a way to not only learn english but could also be thought of as a way for these new immigrants to learn things that the ‘white people’ did in order to fit into mainstream society. These journals could be thought to represent a need to ‘fit in’.