Constructed Narratives in Green Grass Running Water

Write a blog that hyper-links your research on the characters in Green Grass Running Water using Jane Flick’s reading notes.

The section of the book that I have done my research on is pages 126-135. I was particularly drawn to this section because I just had to figure out what Bill Bursom’s garish television display had to do with Machiavelli and why “The Map” was so significant. The following section is of Latisha Red Dog’s encounter with a group of tourists at the Dead Dog Café.

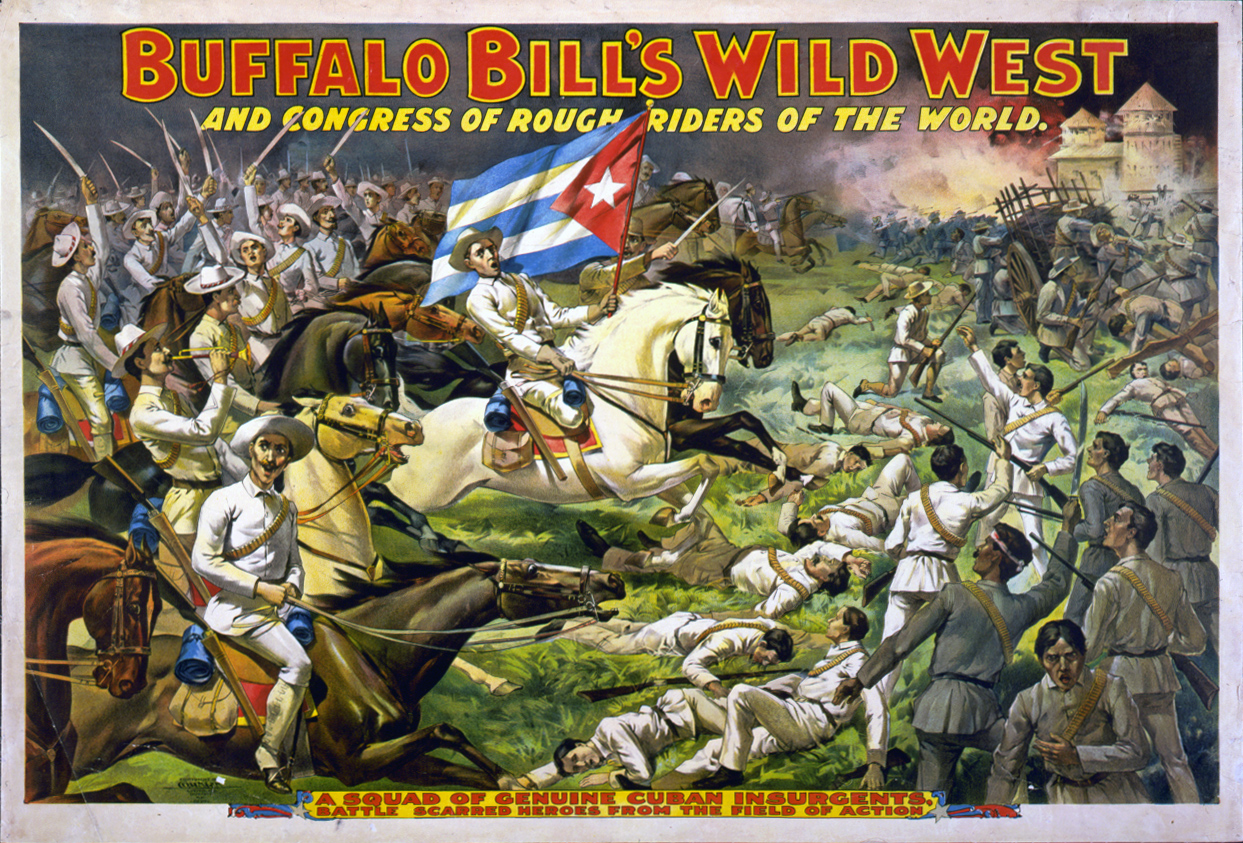

Lionel Red Dog’s employer, Buffalo Bill Bursom is a combination of two historical figures “famous for their hostility to Indians” according to Jane Flick (21). The infamous Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show created a glamorized version of the conflict between the Natives and European settlers for public entertainment. Bill reaps the benefits of having the Indians perform in his show, while suggesting their motive for protecting their rightful homes are primitive and savage. The show promotes a sense of national pride, while suggesting that the Americans have a right to cultivate and build a home on Indigenous land. The second figure that the character is modeled after is Holm O. Bursom, a New Mexican senator. The senator was in charge of drafting a bill that would settle a land dispute between the Pueblos and non-Native folk. The Bursom Bill allowed the state court to settle the disputes, which would have resulted in rulings in the favour of affluent white folk. When the Pueblos became aware of the Bill, they managed to defeat the bill by testifying before Congress of their rights to the land.

The combination of these two historical figures create a character who takes advantage of the Native community by employing someone they know in order to bring in business from the reserve. While Bill is taking advantage of Lionel’s place in the community, he has also set up the pretense that he is helping Lionel get back on his feet so he can afford to go to school. Bill suggests that Lionel and Charlie Looking Dog are interchangeable by telling Lionel that he just needs an ‘in’ to the reserve. In this way, Bill reduces Lionel down to his race while making such derogatory comments such as, “you guys get all that free money” and “[a]ll you guys are related” (80). While not blatantly harmful, the internalized superiority that Bill perpetuates towards the Native community stifles Lionel’s ability to grow and maintain a healthy relationship with his community.

Bill is eager to show off his television display to Minnie Jones, and decides that it is a “unifying metaphor” (128). It is significant that the television display is a map of Canada and the United States. The map is symbolic of a linear, Western logic, that has historically been used to oppress the rights of Native peoples. Minnie Jones asks Bill, “Do all the sets have to show the same movie?” (127). A movie is a constructed narrative, as is a map, as we have previously discussed. When Minnie asks this question, it is as if she is asking if there is room for more than one narrative.

But what about Machiavelli? The Prince, that Bursom keeps recommending, is one of Machiavelli’s best known pieces, and the use of the term ‘Machiavellian’ is attributed to this work. This points to the fact that Bill condones manipulative tactics in order to achieve success in his business. This detachment from moral standards is reflected by Buffalo Bill, Holm O. Bursom, and of the fictional Bill Bursom. Bill goes on to say that this kind of thinking is “outside the range of the Indian imagination” (129). However, I would argue that the existence of alternative narratives exist outside of the oppressive, European imagination.

Latisha’s narrative runs counter to that of Bursom Bill. Here, an Indigenous female successfully runs a business based on co-operation as opposed to a European male running his business on exploitation. Though Latisha could have claimed the role of the “Native victim”, she has taken control of her life and has become a successful business owner. At the Dead Dog Café, Latisha tricks her (often European) visitors into thinking she is actually using dog meat in her food, explaining that it is a “treaty right” (132). Of this strategy, Kerstin Knopf writes that”by referring to (non-Native) written history, [Latisha] gives them the proof they want” (265). By appealing to the Western power structures, and using them to her favor, Latisha is challenging the assumed morality of legal documents. Thomas King says in an interview, “The joke is that Natives did not create that construct. That construct is created by whites and it was created as an oppressive thing. . .those designations were created for advantage and not for ours, and as soon as that advantage shifts then the construct itself needs to be revisited” (Andrews, 163).

Jane Flick suggests that Latisha’s Dead Dog Café may be “a play on Nietzsche’s assertion that “God is Dead” (22). Nietzsche’s statement was made to suggest that the Christian God could no longer serve as the credible source for moral principles and assumptions. Further, this was a rejection of an objective and universal moral law. Similarly, King challenges the biblical Christian stories and the notion of God by sharing alternate creation stories of First Woman and Coyote. In this way, both King and Nietzsche question the validity of an authoritative Christian morality.

Works Cited:

Andrews, Jennifer. “Border Trickery and Dog Bones: A Conversation with Thomas King.” Studies in Canadian Literature. June 1999. Web. 25 July 2016. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/SCL/article/view/14248

Donaldson, Laura E. “Noah Meets Old Coyote, or Singing in the Rain: Intertextuality in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Studies in American Indian Literatures. 2.7.2 (1995): 27-43. JSTOR. Web. 25 July 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20736846

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes.” Green Grass, Running Water.Toronto: HarperCollins, 1994. Print.

“God is Dead.” Philosophy Index. Web. 25 July 2016. http://www.philosophy-index.com/nietzsche/god-is-dead/

Hallsall, Paul. “Nicolo Machiavelli (1469-1527): The Prince, 1513.” Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University. July 1998. Web. 25 July 2016. https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/machiavelli-prince.asp

Hyslop, Stephen G. “How the West was Spun- Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show.” HistoryNet. 8 May 2008. Web. 25 July 2016.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2010. Print.

Knopf, Kerstin. Aboriginal Canada Revisited. University of Ottawa Press, 2008. Google Books. Web. 27 July 2016. https://books.google.ca/books?id=VmGuDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA265&lpg=PA265&dq=latisha+red+dog&source=bl&ots=HIKM2wUJ14&sig=ATh4w524Pio-6BlHRX-7XrEZoYY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj70I7Y5pTOAhVQ42MKHRCNBhsQ6AEIHTAA#v=onepage&q=latisha%20red%20dog&f=false

Martinez, Mathew, San Juan Pueblo. “All Indian Pueblo Council and the Bursom Bill.” New Mexico History. Web. 25 July 2016. http://newmexicohistory.org/people/all-indian-pueblo-council-and-the-bursum-bill

Wernitznig, Dagmar. Europe’s Indians, Indians in Europe: European Perceptions and Appropriations of Native American Cultures from Pocahontas to the Present. University Press of America (2007): 84-89. Google Books. Web. 27 July 2016.

John Wayne movies and many other Westerns portray Native Americans in one or two prototypes. They are often either portrayed as a helpful guide in navigating the wilderness in a subservient role to the white protagonist, or people to be conquered in order to gain rights to a land that is ‘rightfully’ theirs. The exploration and domination narrative that is so prevalent in settler and Western narratives promotes the claims toward a land that is in need of cultivation. By portraying the Native American population as primitive, the colonial narrative justifies their brutality by asserting authority. The Four Old Indians change the outcome of the John Wayne movies in order to assert their presence in a land that is their home, not succumbing to the claims of ownership by the European settlers.

John Wayne movies and many other Westerns portray Native Americans in one or two prototypes. They are often either portrayed as a helpful guide in navigating the wilderness in a subservient role to the white protagonist, or people to be conquered in order to gain rights to a land that is ‘rightfully’ theirs. The exploration and domination narrative that is so prevalent in settler and Western narratives promotes the claims toward a land that is in need of cultivation. By portraying the Native American population as primitive, the colonial narrative justifies their brutality by asserting authority. The Four Old Indians change the outcome of the John Wayne movies in order to assert their presence in a land that is their home, not succumbing to the claims of ownership by the European settlers. In The Bush Garden, Northrop Frye presents two aspects of nation-building in the concepts of identity and unity—identity derived from culture and imagination, and unity rooted in politics and an international perspective towards the nation (xxii). Frye describes Canada as an “obliterated environment. . .with its empty space, its largely unknown lakes. . . [and] its division of languages” (xxiii). Frye presents the physical landscape as an antagonistic force against the unity of the country, without acknowledgement of the people who have occupied, and have knowledge of, this land prior to colonization. From this metaphor, one can assert that it is impossible to create a unified identity when one does not include all of the land, and the voices of the people who occupy it. Though he looks to rejects the forces of colonialism on literature, Frye enforces the logic that it falls upon.

In The Bush Garden, Northrop Frye presents two aspects of nation-building in the concepts of identity and unity—identity derived from culture and imagination, and unity rooted in politics and an international perspective towards the nation (xxii). Frye describes Canada as an “obliterated environment. . .with its empty space, its largely unknown lakes. . . [and] its division of languages” (xxiii). Frye presents the physical landscape as an antagonistic force against the unity of the country, without acknowledgement of the people who have occupied, and have knowledge of, this land prior to colonization. From this metaphor, one can assert that it is impossible to create a unified identity when one does not include all of the land, and the voices of the people who occupy it. Though he looks to rejects the forces of colonialism on literature, Frye enforces the logic that it falls upon.

This is a blog created for ENGL470. The course looks to examine European and Indigenous narratives in Canadian literature, and how they contribute to the notion of identity.

This is a blog created for ENGL470. The course looks to examine European and Indigenous narratives in Canadian literature, and how they contribute to the notion of identity.