Being able to coach an individual team and oversee all the teams in the club comes with many exciting unknowns every season. Thoughts swirl around in my head, including but no limited to:

“how can I get the best out of each athlete I coach to maximize their potential?”

“What split decisions am I going to make during a game that will turn the tides and put in a better place to win?”

“Will the club thrive with the coaches in the roles and age categories they are in?”

“Will we be off better at the end of the season this year than last?”

The intrigue of those unknowns, and the balance between the factors I can and cannot control, against those I can and cannot influence, against those I cannot control at all provides optimism and drive to press for positive outcomes on all fronts. Not all thoughts are exciting however, but the lack of fanfare or allure attached to these thoughts doesn’t make facing them any less necessary:

“Will there be any issues this year?”

“What will those issues be?”

“How can I prepare in advance, in order to address these issues as they occur?”

“Which parent is going to be the one that comes unglued?”

“Will this be the year I just tie up the shoes and say I don’t need this added stress in my life?”

Over my entire coaching career I have had to ask myself all of these questions at the beginning of the season. But as much as I would like to focus on the positives, today we are going to focus on the dark shadow that lurks in the back of the mind of any coach, manager, or administrative body in competitive youth sports.

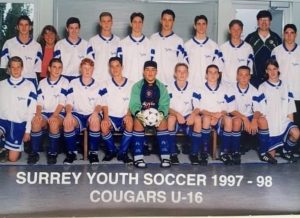

Let’s rewind 20 years ago. I am in my mid teens playing multiple sports. I enjoyed playing them all but really enjoyed playing volleyball the most, with rugby and baseball being close behind. I played on teams of various levels, “house” style fun leagues all the way up to and including high performance, high stakes, ultra competitive teams. My parents never really pushed me towards one or the other, rather choosing to sign me up if I asked and taking that as an indication that I enjoyed it. Back then, “private coaching” and “sports psychology.” were not something that the average athlete participated in while competing in sports. These were emerging phenomenon in their infancy, and words that were only beginning to enter the realm of sporting competition as factors to be taken seriously. Kids would go to tryouts, both in high school and in the community, and teams would be selected either via a phone call or a list posted on a wall. With that came a range of emotions for all hopefuls: heart break all the way to excitement. I experienced the full range of that spectrum, multiple times. With each scenario came character building and learning opportunities. The one thing that was consistent in my household was that there was never EVER “hand-holding” or sense of entitlement. When I made a team I got a pat on the back from my parents and a good job. When I got cut from a team and I was crying beside my bed I got a rub on the back saying “it’s ok” and a “you did your best.” At no time was there any hate or ill feelings exhibited by my parents towards the coach who selected the team, or any insinuations of favoritism towards the school or association. I would handle the inevitable few days of feeling sad or angry, and life would go on. I would be back outside throwing a ball with my dad, playing basketball with my brother, or throwing a football with friends. The love never subsided, nor should it have at any time. I moved on and I would be right back there the next year, with fresh initiative for tryouts, with the objective being a better outcome.

Over the past 20 years the interaction between coaches/managers/administrators and parents has changed drastically. My coaching career started in 2001. In my early days I coached school volleyball and basketball. I was able to choose teams, make cuts, and plan a season with the team that was chosen. My parents were supportive and happy through the process, even though my role on the landscape had drastically cahnged. This remained the “norm” for many years. Then, in 2009-2011 I started to see a shift. During this shift in the landscape, there were more news articles of legendary coaches at the youth level stepping down and more news of parents fighting at hockey arenas. In hindsight, which we often say is 20/20, I don’t see this as an accident. Over these past 20 years I have been able to watch and experience the change in culture that has swept through competitive youth sports. This change has forced coaches to modify and change how they interact not just with athletes but, perhaps more importantly, with parents.

In the past five years, I have had parents demanding in person meetings or phone calls to discuss why their son or daughter was cut. I have fielded abusive emails or phone calls due to their kids, in their eyes, not receiving enough playing time. Parents have taken it upon themselves to coach from the sideline or fight with other parents. Parents have openly gossiped, often within earshot, about decisions coaches have made during games. There have been dirty looks and profanity directed at coaches or other parents. Parents now get upset that their kid was not chosen as captain, or was not played. Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of all of this, is that these behaviours are directed at coaches who coach for the love of the game and put them in terrible situations that they do not deserve. These are coaches who take time away from their family and their hobbies, in order to develop not only self but others. 2013-2017 saw a massive surge on parents thinking all kids needed to win a medal, whether it was first, second, or participation.

Coaches not only need to be masters of their respective technical trades, but also masters in listening, interacting, choosing their words carefully, and acting the amateur physiologist not only in regards to their players but to their players’ parents. This is the era of lawsuits for the major, the frivolous, and everything in between. This presents a backup in the civil court system (another matter entirely), that puts disproportionate pressure on critical legal infrastructures and processes. I opened with questions I ask myself at the outset of every season. The new questions include “Where did we as a society go wrong and feel having mutual human respect was not needed:

Saying one thing, yet doing another?

Not responding to emails?

Slandering or fabricating lies to create tension?

Manufacturing animosity?”

The new reality is that coaches put themselves in the cross hairs, everyday, doing what they do. For all the emotional output that we field in a given year, we are capable of emitting emotion too and do so regularly. For me this takes the form of, when I start a season, remembering the player who said “thank you David” or the team that signed the Thank You card. It takes the form of remembering the player who told me my influence played a part in their not slicing their wrists. It takes the form of the player who came back years later to coach after their playing career was over. It takes the form of the parent who shakes my hand and says thank you for everything. These are the positive interactions that keep me pressing forward on the psychological side of the equation. These are the positive that keep me coming back, making me want to do it again, season after season. I know I’m not alone. This is why many coaches come back and coach again, because at the end of the day if our interactions with parents and player are able to impact one life in a positive way, that is why we do what we do and it is what makes this all worth it…..

(Currently writing a future New York Times Best Seller Stay Tuned)