5. “If Europeans were not from the land of the dead, or the sky, alternative explanations which were consistent with indigenous cosmologies quickly developed” (“First Contact”43). Robinson gives us one of those alternative explanations in his stories about how Coyote’s twin brother stole the “written document” and when he denied stealing the paper, he was “banished to a distant land across a large body of water” (9). We are going to return to this story, but for now – what is your first response to this story? In context with our course theme of investigating intersections where story and literature meet, what do you make of this stolen piece of paper? This is an open-ended question and you should feel free to explore your first thoughts.

———————————————————————————————————————-

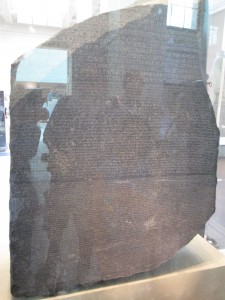

This story of the two twins presents a perplexing a challenge to what is arguably the most powerful embodiment of Western civilization: the written word. The most famous artifact housed in the British Museum, the Rosetta Stone, contains the key to understanding an entire civilization. It is through the written word that Hammurabi manages to assert control over his newly conquered dominion. The writings of Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle survive to this day and continue to be studied by scholars the world over, championed as the fountainhead of Western thought. Latin, though a dead language, continues to thrive on paper and weaves together the various cultures of Europe into the singular conglomerate, a European mega-cultural complex. The Bible binds billions of believers to a common faith for millennia with a text that has remained relatively unchanged since AD 325. The written word and its promulgation is responsible for stasis and change, power and dissension, belief and disbelief. Does the suggestion that all written word is somehow insidious, that it is somehow inferior to the spoken word, undermine the legitimacy of Western culture as a civilization?

It is unmistakeable that Robinson’s narrative mirrors the Biblical account of Adam and Eve: there exists a forbidden truth that, once discovered, can bring harm into the world. Furthermore, it is through disobedience that the dissenters are exiled from Eden, reinterpreted as North America in Robinson’s story. It is ironic that this story, which attempts to cast Western written tradition in a critical and negative limelight, inevitably references one of the most influential texts in Western culture. It is also important to note that in this Indigenous account of good and evil, Robinson has positioned his people as the good guys, much in the same way that Christian settlers see themselves as the morally upright race ordained to educate the heathens. Yet what makes his story different is that his Eden was not left barren; the Indian people continue to live in paradise. They are the unfallen people. Perhaps Robinson wants to provoke the audience to re-examine the basis and legitimacy of the story that serves as the moral beacon of the Western world.

Robinson’s adoption of the forbidden tree narrative demonstrates that the boundaries delineating oral and written tradition is rather porous and allows for the osmotic interchange of ideas and genres. Just as Western anthropologists attempt to crystallize the Aboriginal oral tradition into static anthologies rendered understandable and palatable to the Western audience, Robinson does the reverse by thawing the Biblical narrative of evil entering the word and contextualizing it in an Aboriginal perspective, giving prestige to the Aboriginals and employing the narrative as a defence to justify their claims of belonging to this land. We can learn a lot about this repurposing and repackaging of narratives if we investigate the underlying motives involved in their appropriation.

Salisbury Cathedral: home of one of the four (and the best preserved) surviving manuscripts of the Magna Carta. How do institutions like the church exert power through the written word?

Robinson’s story challenges the ways in which laws are crafted and which laws are seen as just. Since the first laws were codified, the people of Western civilization have subjected themselves to the written word. The triumph of the people over the absolute monarch, and the (re)birth of democracy in Europe with Magna Carta is really the enslavement of all men under a common constitution, under which they can all be given a limited form of freedom. Free men must subject themselves to those who are most able to interpret the law and the most convincing of speakers able to move the judge or jury. Therefore, a society bound together by a piece of paper (or volumes of it) is susceptible to exploitation and tyranny from an elite few, armed with rhetoric to tip the scale in their favour. By attaching connotations of “lies” and “stolen” to the written word, Robinson highlights the weaknesses and vulnerability of depending on written contracts and obscure documents to govern a living and evolving society. Could Robinson’s challenge suggest the necessity of enacting alternative forms of legislature and re-defining justice outside the monolithic behemoth that we call the Canadian legal system?

Works Cited

Choi, Timothy. “Rosetta Stone.” 2014. JPEG file.

Choi, Timothy. “Salisbury Cathedral.” 2014. JPEG file.

Robinson, Harry. Living by Stories: a Journey of Landscape and Memory. Compiled and edited by Wendy Wickwire. Vancouver: Talon Books2005. (9-10)