Chinook Salmon in British Columbia

These chinook salmon getting ready to spawn will eventually die and provide nutrients to many other forms of life. (The Davis Enterprise/Ken W. Davis)

Do you enjoy opening the oven to a tasty salmon fillet? Or perhaps you know someone who appreciates the odd angling trip out of Campbell River? If you live in the coastal Pacific Northwest then you are likely familiar with the importance of salmon to regional markets and diets. In 2005, the BC recreational fishery and supporting businesses yielded an estimated $865 million, contributing to the $2.2 billion that comprises the province’s total earnings from seafood and other fish-related industries. Chinook salmon in particular have been described as a foundation for recreational fisheries throughout BC due to their large size and are important to commercial and aboriginal fisheries. However their importance goes far beyond human use; chinooks and other salmon are important for maintaining biodiversity, with spawning runs providing a rich exchange of food and nutrients between sea and land. Additionally, salmon serve as a food source for larger animals: it is estimated that chinooks compose 78% of Southern Resident killer whales’ summer diet, and 97% of their annual diet. Considering the popularity of summertime whale watching in the region, we can see that chinooks can have unexpected economic advantages.

Chinook salmon are a valuable resource to the companies like Sonora Fishing Resort and the recreational fishers across BC who seek to catch them. (https://sonoraresort.com/activities)

What’s the Problem?

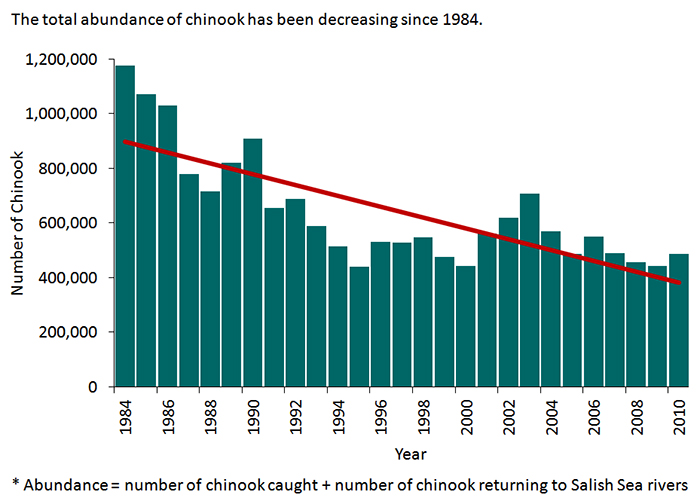

Unfortunately their importance alone has proven insufficient in the management of chinooks. Those who rely heavily on chinook salmon are beginning to worry: over the last 30 years, chinooks in a wide range of areas have been on the decline. Numerous studies conducted over the last decade have suggested that multiple Pacific chinook stocks are in trouble, with significant reductions noted in both scientific and economic reports. Stock declines have been reported as far north as Haida Gwaii and the Skeena River near Port Rupert, and as far south as the Sacramento River in California. Owing to their importance, there have been many attempts to determine the causes. Suggestions range from poor ocean conditions resulting from climate change, to human factors such as overfishing and coastal development.

The abundance of chinook salmon in the Salish Sea since 1984 highlighting one of the many regions reporting a decline in chinook salmon abundance. (USEPA 2014)

There have been ongoing efforts to reverse this decline such as the regulation of salmon fishing and improving their habitat. One course of action that has proven popular is the implementation of hatchery programs, where sperm and eggs from wild salmon are collected and used to rear juvenile salmon for the purpose of releasing them into the wild. The intention is that these hatchery salmon will survive to spawning age and contributing juveniles to wild population to restore a population that has apparently become too small to restore itself. However, the results of hatchery projects throughout the province have been mixed with some working quite well to help save chinook salmon such as the Cowichan River, and some such as the Gillard Pass Fisheries Association that have seen chinook populations in the Phillips River remain stagnant despite over 30 years of work and over 2 million chinooks released into the Phillips watershed. Extensive studies suggest that this is because salmon hatchery programs may have adverse effects on the natural populations, or may release chinook salmon before they are fully developed and ready to face harsh ocean conditions. As a result, hatchery programs may not always be effective in helping a population survive.

Rupert Gale checking up on chinooks that will have eggs and sperm collected to carry out a hatchery program. (GPFA 2014)

GPFA and the Phillips S1 Chinook Trial

Gillard Pass Fisheries Association (GPFA) is trying to fix this problem in the Phillips River through a unique program called the Phillips S1 Chinook Trial and believe that it may be the solution for other struggling chinook populations. Where typical hatchery programs grow chinook for three months, the S1 program grows them for a full year in freshwater with help from the Omega Pacific Hatchery. It is thought that by releasing the chinook after a year, they are more capable of finding food sources, avoiding predation and disease, and are more resilient to changing ocean conditions than younger ones. GPFA’s goal is to recover the Phillips River chinook population to a healthy and self-sustaining level with the S1 program.

The eggs and sperm are first collected from chinooks at the Phillips River before they are transferred to the Omega Pacific Hatchery to be fertilized, incubated and reared. During this process, the approximately 40,000-50,000 juvenile salmon are fed slowly in an attempt to mimic wild conditions. At the end of the year, Rupert Gale (President of GPFA) and Carol Schmitt (President of Omega Pacific Hatchery) transport half of the fish to the head of the Phillips River’s arm to be held for a week in sea-pens while the other half are moved to net-pens in Phillips Lake. This allows for the chinook yearlings to remember where they are released and makes sure that they will return to the Phillips River to reproduce. Coded wire tags (CWT), which allow the fish to be traced back to a specific group, are attached to all fish from the S1 program so they are identifiable when caught by fisheries or by those conducting studies of the GPFA Phillips River S1 program. The adipose fin of S1 fish is also clipped as an external marker that allows them to be easily identified. The identification of the chinooks allows the GPFA to collect data on the fish to examine the success of the program.

Click here to see the 2011 release of S1 smolts in Action.

A clipped adipose fin is one way GPFA determines a fish is of hatchery origin compared to a wild fish with an adipose fin. It is important to be able to distinguish between wild and hatchery fish to obtain useful data. (GPFA 2014)

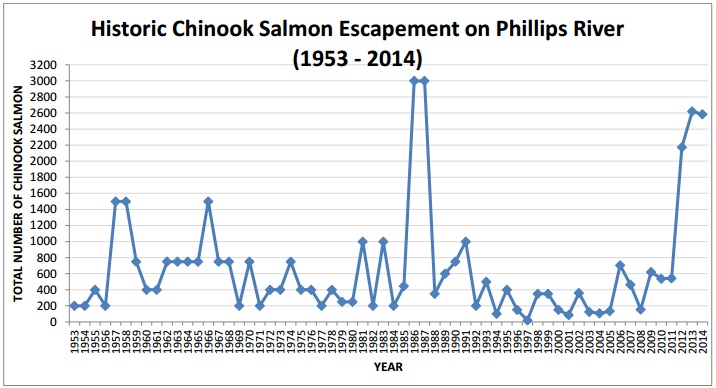

A metric that can be used to evaluate the efforts of the GPFA is the number of adult Chinook that have returned to mate in the Phillips River. Gillard Pass identifies that the Phillips River watershed has a capacity of 2500 mating adults that would provide a stable and self sustaining amount of chinooks. The S1 chinooks that GPFA have released into the wild have been returning as of 2011. In 2012, Gillard Pass estimated that over 2300 adult chinooks returned to mate; this was the largest return seen since the 1980s. In 2013, over 2700 adult chinook returned and in 2014, about 1800 adult chinooks returned to the Phillips. Though the 2013 return surpassed this ‘sustainable capacity’ goal, one will only be able to consider the chinook population in the Phillips River recovered when this number of spawners has reached the goal consistently over several years.

The increasing trend in the Phillips river chinook population since 2012. (Anderson and McCorquodale 2015)

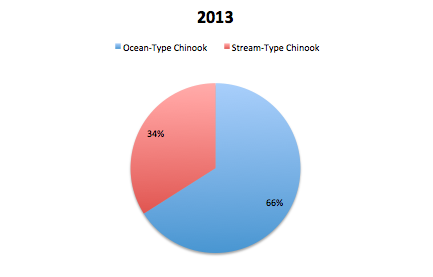

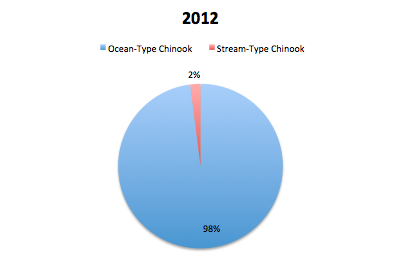

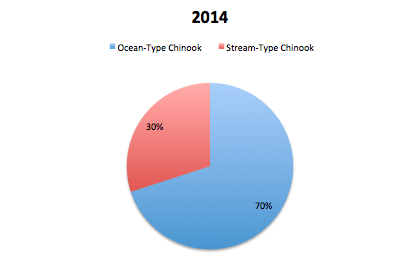

GPFA also hopes to contribute to the strength of the chinook population in the Phillips by restoring the diversity of types of chinooks in the river system. The stream-type chinook, who historically were plentiful in the region but were hurt by logging practices, are trying to be increased by the S1 trial. These stream-type chinook coincide with the early chinook mating season which occurs in June. The other type of chinook found in the Phillips is the ocean-type which returns to mate in the late summer and early fall and is much more prevalent in the Phillips river. In order to evaluate the success of the increase in diversity of the chinook population, the ratio of stream-type to ocean-type chinook in the returning spawners is examined. After reviewing returning spawner data in 2013, they found that 66% of the spawners in the Phillips were ocean-type while 34% were stream-type. In 2014, 70% of the spawners were ocean-type while the remaining 30% of spawners were stream-type. Both of these ratios are dramatically different to the data seen in 2012 where 98% of returning spawners were ocean-type and only 2% stream-type. The increase in stream-type chinook to the Phillips River can be attributed to the success of the S1 trial because S1 chinooks are known to have a stream-type life history where typical hatchery fish are known to have an ocean type.

Learn more about stream-type and ocean-type chinook life histories here:

Returning spawners to the Phillips River by life history type in 2014. (GPFA 2015)

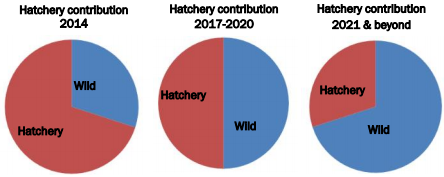

The GPFA also wants to ensure that the increased number of spawners returning are the result of an increase in wild chinooks due to hatchery salmon contributing offspring to the wild population. If an increase is purely the result of hatchery salmon, the wild population could be swarmed by hatchery fish, experience a decrease in survival and lose characteristics that make it distinctly suited to the Phillips river. The percentage of wild salmon in the population compared to the percentage of hatchery salmon in the population is used by the Canadian government and GPFA to assess this concern. The aim is to maintain a less than 50% contribution by hatchery fish in any conservation project and less than 30% for long term hatchery projects. Hatchery contributions represented 61% of the Phillips population in 2014, 36.9% in 2013 and 40% in 2012. It is important to note that this data is skewed by the fact that hatchery fish accounted for a larger portion of the stream-type fish and a smaller portion of the ocean-type fish. This is expected because of the low population of stream-type fish that the GPFA is trying to build with the S1 program.

Current hatchery contributions of the Phillips hatchery program and what GPFA hopes to reduce it to in the future. (GPFA 2014)

Is it Working?

The big question is whether or not all the time and money put in by Rupert Gale, Carol Schmitt, the Gillard Pass Fisheries Association and its many volunteers has paid off. From these early numbers we have covered, GPFA has been able to substantially increase the amount of chinook in the Phillips to a more stable number. It has also increased the diversity of chinook types in the Phillips population. This all suggests that the GPFA and the S1 program is helping to conserve the wild Phillips chinook population which is unique in its history and would be irreplaceable if lost. In addition to conservation of the population, the local recreational and aboriginal fisheries will see benefits from an increase in chinook salmon in the area. However, the high amount of hatchery fish compared to wild fish is cause for concern as it may cause the wild fish to be overrun by hatchery fish and have adverse effects on the unique wild fish that they are trying to save. This will start to decrease if the S1 fish do succeed in contributing offspring to the wild population and especially in the stream-type that currently has a low population of wild fish. The government and the GPFA are taking special care to monitor this ratio and the program will not be considered a success if this problem persists.

There is a lot of time and money invested by many people to ensure that the operations of the GPFA runs smoothly. Is it worth it? (GPFA 2012)

It is important to consider that not all of the chinooks from a single release year have returned yet due to the variability in return years of chinook salmon. Full success of the S1 will not be able to be fully determined until all the fish from a release year have returned, which is expected to have occurred this past fall. The early data outlined is promising but needs to see a larger proportion of wild chinooks in the population to validate the rationale of this program. As a result of the vigorous monitoring carried out by the GPFA, the next couple years of S1 returns will reveal if the program lives up to our metrics of success. Rupert, Carol and the countless volunteers will continue their efforts until this job is done. If successful, we believe the S1 chinook program has the potential to be a key tool for helping struggling chinook populations throughout the Pacific that are experiencing similar problems to the Phillips river chinook salmon.

Volunteers are working hard to accurately monitor the results of the S1 program as chinooks return to reproduce. (GPFA 2013)

Click here for more information on the GPFA

Click here to find out about other projects helping BC salmon

Ask questions or find out more from the authors on twitter:

Cody Carlyle – @codycarlyle1384

Michelle Stevens – @MicheS5

Jack Shannon – @CaptnJackShan

References:

Anderson, K.A. & McCorquodale, D. (2015) Phillips River Mark-Recapture Chinook Population

Study: July – November, 2014. Pacificus Biological Services Ltd.

British Columbia Ministry of Environment (2007) British Columbia’s Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector, April 2007. BC Stats Report.

BC Parks (2015) Phillips Estuary/PNacinuxW Conservancy. http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/cnsrvncy/phillips/ (accessed 23 November 2015)

BC Parks (2015) Cowichan River Provincial Park. http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/parkpgs/cowichan_rv/ (accessed 23 November 2015)

DFO (1999) Lower strait of georgia chinook salmon. DFO Science Stock Status Report D6-12.

DFO (2013) Do You Know: Chinook Salmon. http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/species-especes/salmon-saumon/facts-infos/chinook-quinnat-eng.html (accessed 21 November 2015)

Gillard Pass Fisheries Association (2010) Spawning Times: Annual report 2010.

Gillard Pass Fisheries Association (2011) Spawning Times: Annual report 2011.

Gillard Pass Fisheries Association (2012) Spawning Times: Annual report 2012.

Healey, M.C. (1991) Life history of chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Pages

311-393 in: C. Groot & L. Margolis (eds.) Pacific Salmon Life Histories. Department of

Fisheries and Oceans, Biological Science Branch. UBC Press, Vancouver.

Hocking, M., Okey, T.A., Ballin, L., & Hatfield, T. (2015) Phillips Arm Aquatic Resource

Assessment. Consultant’s report prepared for the Kwiakah First Nation by Ecofish

Research Ltd.

Holtgrieve, G.W. & Schindler, D.E. (2011) Marine-derived nutrients, bioturbation, and

ecosystem metabolism: reconsidering the role of salmon in streams. Ecology, 92, 373-85.

Hume, M. (2009) Hatching a plan to solve B.C.’s salmon crisis. The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/hatching-a-plan-to-solve-bcs-salmon-crisis/article1371958/

Kwiakah First Nation (2009) Phillips Estuary Conservancy.

http://www.kwiakah.com/Phillips_Estuary_Conservancy.htm (accessed 3 November 2015)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries (2010) Species of Concern:

Chinook Salmon. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/species/chinooksalmon_highlights.pdf (accessed 8 November 2015).

Noakes, D.J., Beamish, R.J. & Kent, M.L. (2000) On the decline of Pacific salmon and speculative links to salmon farming in British Columbia. Aquaculture, 183, 363-386.

Regan, G. (2005) Canada’s Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon. Fisheries and

Oceans Canada.

Roscoe, David W. & Pollon, Christopher. (2010) Report Cards for Three B.C. Recreational

Fisheries. Watershed Watch Salmon Society.

Rudan, P. (2011) Journey begins for Phillips chinook. Campbell River Mirror.

http://www.campbellrivermirror.com/news/120413599.html

Springtide Whale Watching (2013) Save the salmon, save the whale: the relationship between

salmon & southern resident killer whales

https://www.victoriawhalewatching.com/save-the-salmon-save-the-whales-the-relation

ship-between-salmon-southern-resident-killer-whales/ (accessed 11 November 2015)

Sonora Resort. https://sonoraresort.com/ (accessed 21 November 2015).

Tremayne, S. (2013) Salmon spawning in Putah Creek. The Davis Enterprise.

http://www.davisenterprise.com/local-news/ag-environment/salmon-spawning-in-putah-creek/

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2014) Salish Sea Report: Chinook Salmon. http://www2.epa.gov/salish-sea/chinook-salmon (accessed 8 November 2015).

Williams, D. & McCorquodale, D. (2014) Phillips River Mark-Recapture Chinook Population

Study: August– October, 2013. Pacificus Biological Services Ltd.