With no solution on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the concept of personal thermal management is becoming a promising alternative to renewable energy resources. Personal thermal management focuses on cooling or heating the human body instead of an entire building. This is the most cost-effective way to solve the energy dilemma.

A team of researchers at Stanford University have found one way of reducing energy consumption by demonstrating the use of nanoporous polyethylene (nanoPE) as a textile for human clothing. They predict that this fabric could reduce the amount of energy used for air conditioning.

A portion of heat from our bodies is released through the emission of IR radiation in the range of 7 – 14 nm. Many of the fabrics we wear have chemical groups that absorb radiation in that range. One fabric, Polyethylene, is transparent to IR but it is also transparent to visible light which is not desirable as it causes our bodies to increase in temperature.

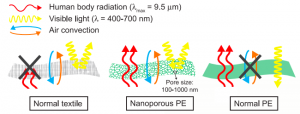

Figure 1. The schematics of human body radiation, visible light and air convection. Source: Cui et al., 2016

However, Ci Yui and his colleagues at Stanford University hypothesized that if polyethylene had pores between 50 – 1000 nm in diameter then it could scatter visible light, making it opaque, but still allow IR to pass through. Fortunately, such a material already exists and is commercially available. Lithium-ion batteries use nanoPE as a separator between anodes and cathodes to prevent electrical shortages.

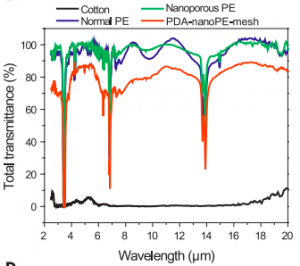

Figure 2. The total IR transmittance of bare skin, normal PE, nanoPE, cotton, Tyvek and PDA-nanoPE-mesh. Credit; Cui et al., 2016

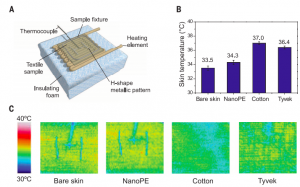

Yui and his team used a device to simulate the heat output of skin and tested the cooling effects of nanoPE, cotton and Tyvek, a fibrous polyethylene textile manufactured by DuPont. They found that compared to cotton, nanoPE was able to cool bare skin by 2.7°C more. In addition, nanoPE was the only material of the three tested to reveal the H-shape, mimicking bare skin, because of its IR transparency.

Figure 3. Thermal measurement nanoPE, cotton and Tyvek. (A) The device used to simulate the heat out put of skin. A thermocouple is used to measure temperature. (B) The thermal measurement of each material. (C) Thermal imaging of bare skin and the three materials tested. Source: Cui et al., 2016..

“That may not sound like much, but in terms of energy savings it actually could be huge”, says Svetlana Boriskina of Massachusetss Institute of Technology, who wrote on the Yui’s findings in Science. She points out that setting a home’s thermostat a few degrees lower can cut energy use up to 45%.

To make the material more appealing, Yui and his team coated the nanoPE to wick away moisture to keep the wearer feeling dry.” Yui and his colleagues may have demonstrated another function of nanoPE, but more research is needed to test for its comfort, durability and a way to colour the material with dyes that won’t block IR radiation.” adds Boriskina.

-Ashlea Ahmed

Resources:

Hsu, P.; Song, A.; Catrysse, P.; Liu, C.; Peng, Y.; Xie, J.; Fan, S.; Cui, Y. Radiative Human Body Cooling by Nanoporous Polyethylene Textile. Science [Online] 2016, 353, 1019-1023 http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/353/6303/1019.full.pdf (accessed Mar 4, 2018).

Scientific American. Newest Material Makes Coolest Clothing Around.https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/new-material-makes-coolest-clothing-around/ (accessed Mar 4, 2018).